Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

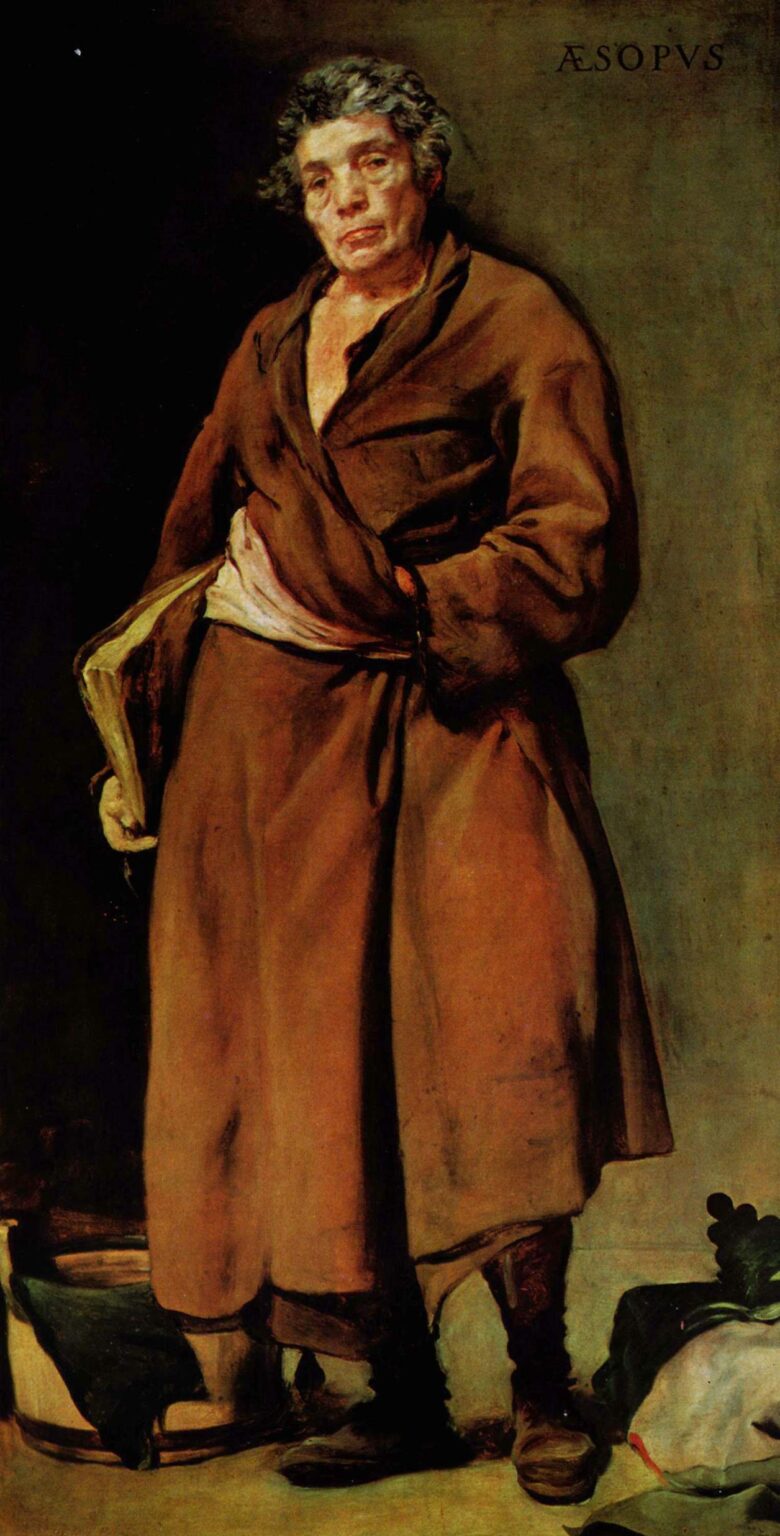

Diego Velazquez’s “Aesop” of 1640 is one of the most searching portraits of wisdom ever put to canvas. It presents the legendary fabulist not as a marble ideal or a courtly sage but as a weary, sharp-eyed thinker standing in a plain room, wrapped in a worn brown robe and clutching a book. The painting’s power lies in its quiet refusal of grandeur. Velazquez strips away ornaments and parable scenes and gives us a single human figure, life-size and near the picture plane, whose intelligence emerges through attitude, gesture, and paint. In this economy of means, the artist turns a mythic author into a living presence, creating a model for how painting can embody thought without depicting it.

The Courtly Moment

The portrait belongs to Velazquez’s mature Madrid years, when he was court painter to Philip IV and occupied a pivotal position at the intersection of power, literature, and art. It was likely conceived for an environment where images of philosophers and poets adorned walls as visual companions to learning and conversation. Instead of heroicizing Aesop with antique attributes, Velazquez chose a vernacular realism aligned with Spanish naturalism of the period. The result harmonizes with the larger project of his court portraits: a relentless attention to presence over rhetoric, to the dignity of the body as it stands in light. In the world of palaces and titles, “Aesop” offers a counter-image of authority rooted in intellect and experience rather than rank.

Composition and Stance

Velazquez constructs the figure almost like a monolith. Aesop rises from the lower edge to near the upper margin, his robe describing a vertical mass slightly canted at the hips. The stance is casual but firm. One hand disappears beneath the sash at the waist, as if warming itself or guarding the body’s center; the other supports a thick book whose dog-eared pages protrude. The head tilts forward, the gaze drops just past the viewer, and the lips relax into a nearly expressionless line. This articulation of posture achieves a delicate equilibrium: Aesop is accessible yet self-contained, engaged yet not performative. The slightly off-balance contrapposto keeps the body alive, inviting the eye to travel from the tousled hair down the robe’s seam to the boots, where shadows pool and light picks out leather and stitching.

The Book as Instrument

The book in Aesop’s hand functions as both attribute and tool. It is not a gilded folio but a used volume, its edges softened by handling. Velazquez paints it with broad, quick strokes, emphasizing weight rather than ornament. The book anchors the hand, secures the figure’s left flank, and reminds us that Aesop’s authority comes from words crafted into stories of animals and humans. Holding the book rather than reading from it suggests readiness—the capacity to summon a tale at need. The painter’s decision to avoid decorative clasps or calligraphic titles directs attention to use-value, reinforcing the painting’s commitment to a lived rather than idealized wisdom.

Light, Palette, and Atmosphere

The illumination is sober and oblique, entering from the left to articulate forehead, cheekbone, collarbone, and the thick folds of the robe. The palette is severe and warm: umbers, siennas, and soft blacks interwoven with ochre and a few small notes of gray-green. The background is a muted plane of earthy tone that transitions from darker left to lighter right, a Velazquez hallmark that embeds the figure in breathable air. The limited color range pushes attention toward tonal architecture. Flesh and fabric are modeled with cool and warm variations rather than local color shifts, so that light behaves as a living substance. This chromatic restraint underscores the portrait’s ethical clarity. Nothing distracts from the human presence.

The Face and the Work of Time

Aesop’s face is the painting’s center of gravity. Velazquez renders it with a few decisive planes: the broad forehead touched by light, the heavy eyelids casting shadows, the nose modeled by a narrow band of illumination, and the softly sagging mouth. The features suggest age and use. They also indicate a life lived in the realm of tact and observation rather than brute power. The eyes, reddened at the rims, carry a fatigue that reads as attentiveness. They have watched people long enough to understand their habits and self-deceptions; they have watched animals long enough to translate their behaviors into stories. Time is the portrait’s invisible subject. The paint does not flatter; it records. Yet within this unflinching study there is warmth. The head leans slightly toward us, conferring intimacy rather than distance.

The Robe as Philosophy

The robe is more than costume; it is the materialization of the philosophical vocation. Its coarse fabric, patched seam, and utilitarian drape declare allegiance to necessity over show. Velazquez revels in how the cloth takes light, laying in long, supple strokes that swell where fabric bunches and thin where it stretches across the body. The sash at the waist bites into the mass, creating a hinge from which the robe’s weight falls. This play of mass and tension gives Aesop’s body gravitas and texture, making wisdom palpable. The robe is the visual counterpart to the fable: a simple covering under which the most sophisticated matters can be carried.

Scale and the Ethics of Looking

Velazquez’s choice of near life-size scale does crucial ethical work. The painting meets a spectator at human proportion, refusing theatrical distance or diminutive devotional scale. This equality of size encourages a mode of viewing that is neither worship nor condescension. We stand with Aesop in the same room, as though we have interrupted him between tasks. His body occupies the vertical center; his head is slightly above our eye line; his feet are planted on the same plane as ours. Such calibrations convert the spectator from an auditor at a lecture to a participant in a conversation. The result is a portrait that advances a quiet argument about knowledge: it belongs to bodies and rooms rather than pedestals.

Gesture and Psychology

The painting’s psychology flowers in small gestures. The right hand, tucked into the robe, signals modesty and reserve. The left hand, curled around the book’s spine, speaks of habit and readiness. The forward-tilted head and unfocused gaze suggest a mind that ranges beyond the moment, perhaps rehearsing a story or distilling an observation. Velazquez refuses overt narrative cues; he trusts the logic of body language to reveal a character comfortable with silence. The effect is of a living pause, a breath held between thought and speech, where the fable-to-come briefly gathers itself.

The Name on the Wall

In the upper right, the inscription “AESOPVS” designates the figure with brisk certainty. The Latinized name is both label and conceptual frame. It confirms identity while inflecting the painting with the memory of classical tradition. Yet the inscription is small and unobtrusive, secondary to paint and presence. Velazquez thereby subordinates textual authority to visual encounter. We are not asked to venerate a name; we are invited to meet a person who happens to carry that name. This priority mirrors the very logic of the fable, where named animals act like people and people learn to read themselves through other forms of life.

Realism and Invention

Scholars have long noted that Velazquez’s philosophers may be portraits drawn from life rather than imaginary reconstructions of ancient figures. Whether or not Aesop’s face derives from a contemporary model, the artist deliberately fuses realism with invention. He constructs a body that belongs to seventeenth-century Spain and clothes it in garments that anchor it in an ordinary present. At the same time, he bestows on the figure the timeless aura of the thinker. This blend accomplishes more than historical verisimilitude. It argues that wisdom does not require exotic distance. It can appear in the familiar, the local, the worn. By building Aesop from the materials of his own world, Velazquez claims the philosopher as a permanent contemporary.

Dialogue with Other Philosopher Portraits

“Aesop” forms a pair with Velazquez’s “Menippus,” often thought to represent the satirist who, like Aesop, wrote in an anti-heroic register. Where Menippus stands with a sardonic squint, garments patched to near-parody, Aesop carries a quieter, inward gravity. Together they stage two modes of critical intelligence: the biting laugh and the observant parable. Compared with the more theatrical “Pablo de Valladolid” or the poignant portraits of court jesters, “Aesop” retreats from performance into thought. The brushwork, though still open, tightens around the head and hands, signaling concentration. The pairing also underscores Velazquez’s habit of giving intellectual labor a human face independent of social class, aligning philosophers, satirists, and entertainers within a single hierarchy of attention.

Brushwork and the Art of Suggestion

The painting exemplifies Velazquez’s late manner of abbreviated description. He indicates hair with a flurry of wiry strokes, letting the dark ground peep through to evoke volume. He models the robe with long, juicy passages that turn in space with minimal blending. He lays the book’s pages with a handful of heavy touches that convince by weight and angle rather than by detail. The face alone receives tighter calibration, but even here edges remain soft, each transition of tone resolving into the next like breath into air. This restraint energizes the viewer’s eye, which must finish the forms. In the gap between mark and illusion lives the painting’s modernity, the sense that we are witnessing thinking in paint.

The Space Around the Figure

Velazquez creates a shallow, resonant space that reads less as architectural interior than as a volume of air. The left side is darker, pushing the figure forward; the right side opens, letting the inscription float on an indifferent wall. At Aesop’s feet, a few objects—fabric, a basket or tub, a scatter of fruit—occupy the ground quietly, as if to remind us that the thinker stands within a world of ordinary provisions. These subdued still-life notes keep the figure’s authority earthbound. The moral reasoning of the fables grows from the same earth that grows grapes; it shares floor space with laundry and buckets. The philosopher’s feet are literally in the room with the tools of daily life.

Moral Intelligence Without Allegory

The brilliance of “Aesop” lies in its refusal to stage an allegory while nevertheless radiating moral intelligence. Velazquez does not paint a fox or a crow, a lion or a mouse. He paints the human capacity to craft such stories, embodied in a person whose face reveals discipline and compassion. The portrait’s moral vision resides in how it teaches us to look. We study the folds of the robe, the droop of the eyelids, the weight of the book, and in that attentive study we practice the very habits the fables recommend: patience, observation, humility. The painting becomes a silent lesson in perception as ethical practice.

Time, Wear, and the Texture of Truth

Every surface in the painting bears time’s signature. The robe’s hem is softened by use. The book’s corners are frayed. The boots show creases from walking and standing. Even the skin carries a map of fatigue. Velazquez does not dramatize these signs; he lets them exist. Their quiet accumulation produces a texture of truth. We believe in this person’s history without being told a story because the objects around him have histories too. The painting thus elevates wear to metaphysical status. Things and bodies are trustworthy precisely because they have been used.

Reception and Legacy

Later painters found in “Aesop” a model of unadorned authority. Realists admired the tonal architecture and the honesty of the face; modernists admired the open brush and the way the painting seems to assemble itself before the eye. The portrait also influenced the representation of writers and thinkers, providing an alternative to the triumphal bust or the sentimentalized scholar. In museums, it continues to recalibrate the room, exerting a gravitational pull that slows viewers to the pace of thought. Its legacy is not merely stylistic but ethical: it proves that respect can be built from silence, light, and the dignity of ordinary materials.

Seeing Anew

To stand before “Aesop” is to be invited to reconsider what a portrait can do. It can replace lofty symbols with the exactness of a person’s stance. It can equate knowledge with attention rather than with costume. It can honor the labor of writing by depicting a hand on a book rather than a hand in a laurel wreath. Velazquez achieves all this without rhetoric. The canvas speaks softly, and in that softness lies its argument. Wisdom, like good painting, wastes nothing, trusts what is necessary, and reveals itself in how it stands in the light.

Conclusion

Velazquez’s “Aesop” is a masterpiece of thoughtful minimalism. With a narrow palette, a humble robe, and a weathered face, it condenses the idea of the fabulist into a figure of humane authority. The painting’s beauty is inseparable from its candor. It shows how attention can turn the simplest materials into vessels for meaning, how a book held at the hip can bear the freight of culture, and how a man in a plain room can represent the perennial sovereignty of intellect. Four centuries later, the portrait still feels contemporary because it defends a truth that neither fashion nor power can unseat: wisdom is a way of being before it is a set of words.