Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

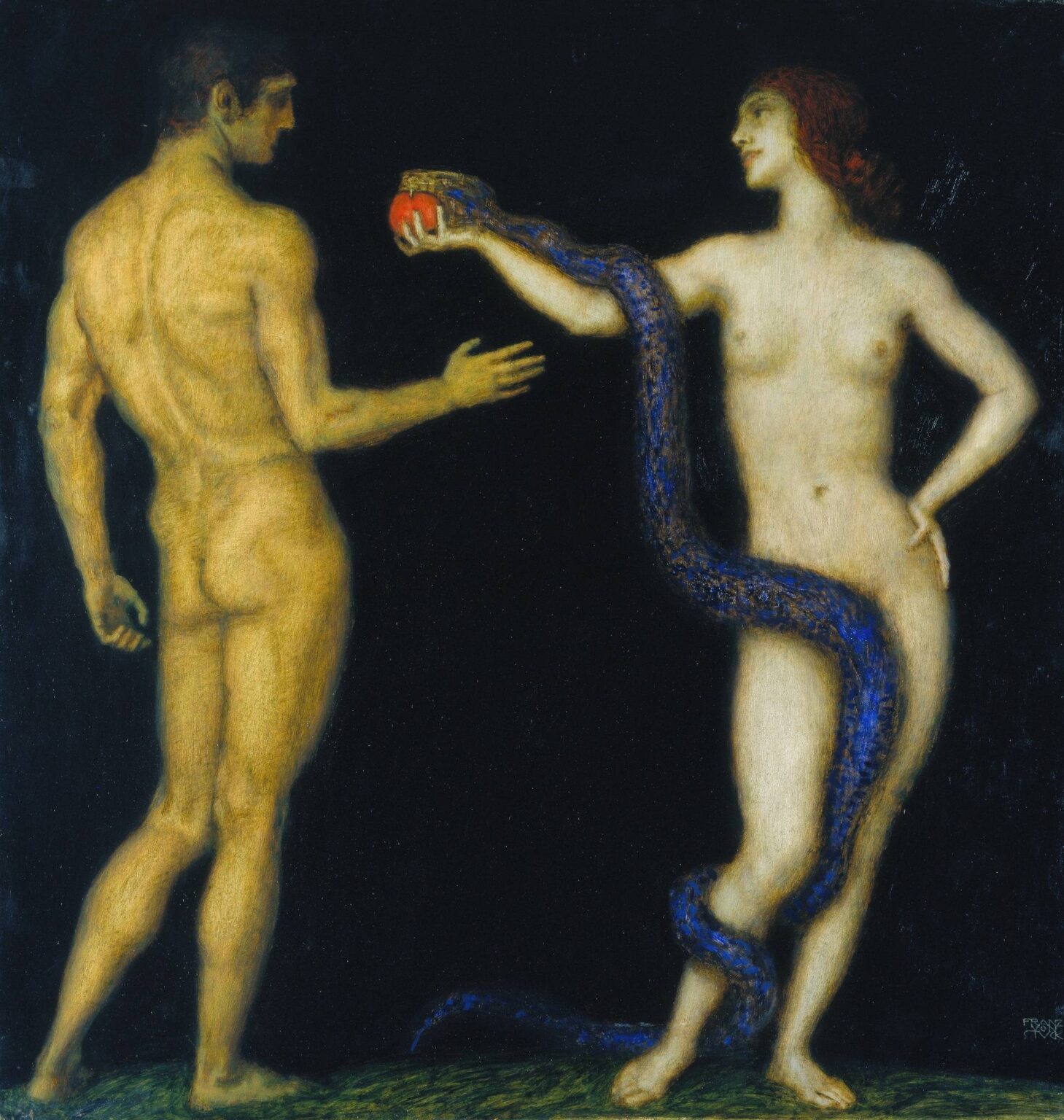

Franz von Stuck’s Adam and Eve (1920) represents a late‑career culmination of the artist’s lifelong engagement with myth, symbolism, and the female nude. In this enigmatic tableau, von Stuck reexamines the foundational biblical narrative with a sobriety of palette and a clarity of form that contrast with his earlier, more painterly Symbolist canvases. The painting presents two nude figures—Eve, vibrant and confident, offering Adam the forbidden fruit entwined with a deep‑blue serpent, and Adam, his back toward the viewer, poised at the threshold of choice. Set against a pitch‑black void, the figures emerge as archetypal embodiments of innocence, temptation, and the imminent fall. Through a rigorous composition, nuanced use of color, and a profound psychological tension, Adam and Eve invites the viewer into a timeless meditation on free will, knowledge, and the human condition.

Historical Context

By 1920, Franz von Stuck (1863–1928) had established himself as one of Germany’s foremost Symbolist painters and influential teachers at the Munich Academy. The aftermath of World War I saw Europe grappling with disillusionment, social upheaval, and a reevaluation of traditional moral narratives. In this climate, artists turned to familiar myths as vehicles for existential inquiry. Von Stuck’s return to the story of Adam and Eve in 1920 reflects both his personal quest for artistic renewal and the broader cultural need to confront the ambiguities of morality after the devastation of war. Having painted an earlier version of Adam and Eve in 1912, von Stuck’s 1920 rendition strips away decorative excess in favor of a more austere, psychologically charged vision, aligning with emergent modernist tendencies toward formal clarity and symbolic depth.

Mythological Narrative and Symbolism

The story of Adam and Eve stands at the heart of Western mythic consciousness, recounting the moment when humanity gained self‑awareness at the cost of innocence. In von Stuck’s interpretation, Eve—the first woman—holds aloft the red fruit of knowledge. The fruit’s vivid scarlet hue resonates against the neutral tones of flesh, marking it as both alluring and forbidden. A sinuous serpent, painted in electric cobalt, coils around Eve’s arm and leg, its presence a reminder of the primal cunning that spurred the Fall. Adam stands with his back to the viewer, his hand reaching tentatively toward the fruit. His posture conveys both desire and hesitation, embodying the human tension between obedience and curiosity. By isolating these figures against a blank background, von Stuck transforms them into universal symbols: Eve as the catalyst of consciousness, Adam as the inheritor of choice, and the serpent as the voice of disruptive insight.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Von Stuck arranges his composition with geometric precision. The painting’s near‑square format emphasizes the symmetry of the human form and the central axis running between the two figures. Eve’s upright stance occupies the right half of the canvas; Adam’s partial figure balances the left. The serpent’s curving form creates a diagonal line that connects Eve’s extended arm to her grounded foot, guiding the viewer’s eye through the image in a single, unbroken gesture. Adam’s reaching arm reinforces this diagonal, positioning the moment of decision at the painting’s heart. The negative space around the figures—an absolute black—eradicates any sense of environment or temporal context, heightening the existential isolation of the scene and concentrating attention on the act of temptation itself.

Use of Line and Form

Line in Adam and Eve serves as both descriptive delineation and expressive emphasis. Eve’s silhouette is defined by smooth, sinuous curves that suggest fertility and confidence, while Adam’s form is articulated with more angular musculature, signaling his strength and sense of uncertainty. Von Stuck employs clean contour lines around the bodies, isolating them sharply from the background. Within those outlines, subtle cross‑hatching of muted browns and greens shapes the musculature and contours of ribcage, shoulders, and thighs. The serpent’s form is drawn with a livelier, almost electric line—its scales implied through short, quick strokes of blue and black. These variations in line quality underscore the painting’s thematic dichotomies: Eve’s assured poise against Adam’s wavering posture, smooth innocence against the serpent’s writhing insight.

Color Palette and Tonal Contrast

The restrained palette of Adam and Eve hinges on the interplay between flesh tones, deep blue, and a touch of red. The human figures are painted in a harmonious blend of ochre, sienna, and ivory, creating a lifelike warmth that contrasts with the serpent’s cool ultramarine. Eve’s hair, rendered in a natural reddish‑brown, picks up the fruit’s red accents, tying her to the act of transgression. Adam’s darker hair and shading underscore his hesitation and the weight of responsibility. The absolute black background serves as a field of nothingness, against which the figures and their symbolic elements appear to float. This stark tonal contrast intensifies the painting’s psychological charge: the color relationships literally illuminate the moment of moral illumination.

Light, Shadow, and Modeling

Von Stuck’s modeling of form relies on a softly diffused light source, as though an unseen beam gently caresses the bodies. Highlights fall along the planes of shoulders, collarbones, and thighs, sculpting the figures in subtle relief. Shadows are rendered through layered glazes of earth tones, darkening the recesses beneath arms and behind knees. The serpent’s scales catch light with a cooler, more reflective gleam, distinguishing its texture from human skin. The overall effect is a three‑dimensional realism that remains poetic rather than hyper‑naturalistic. By employing controlled light and shadow, von Stuck infuses the scene with an ethereal stillness, as if time itself holds its breath in anticipation.

Texture and Brushwork

A close examination of the surface reveals von Stuck’s deliberate brushwork. The flesh is smoothed through fine, almost imperceptible strokes, creating a velvety finish that invites tactile contemplation. In contrast, the serpent is painted with more visible, rhythmic strokes, lending its skin a subtle iridescence. Eve’s hair shows a combination of linear strokes and softer blending, capturing both individual strands and broader mass. The grass beneath their feet, though minimally indicated, is rendered with quick, feathery touches of green and brown, grounding the figures in a hint of natural setting. These textural variations heighten the painting’s sensory richness while reinforcing the thematic tensions between human form and animal cunning.

Psychological and Emotional Resonance

The emotional impact of Adam and Eve lies in the moment of poised decision. Eve’s confident smile and direct gaze convey an almost triumphant embrace of knowledge, while Adam’s back‑turned stance and outstretched hand suggest both longing and apprehension. The serpent, with its head raised and eyes fixed on Adam, seems to whisper the irrevocable consequences of choice. This psychological triangulation—woman as instigator, man as chooser, serpent as instigator—invites viewers to inhabit each role in turn, reflecting on internal conflicts between obedience and freedom, innocence and experience. Von Stuck’s ability to distill such complex emotions into a single, silent tableau speaks to the enduring power of myth to illuminate human psychology.

Relation to Early Biblical Interpretations

Von Stuck’s 1920 Adam and Eve consciously aligns with and diverges from centuries of artistic interpretations. Renaissance masters emphasized lush paradisiacal settings and dramatic gestures, while Northern painters often dwelled on moral didacticism. Von Stuck removes the Edenic backdrop, presenting the narrative in an abstract void that reflects 20th‑century existential concerns. His figures lack the ornate symbolism of medieval art—no fig leaves, no luxuriant flora—yet the essentials of the story remain unequivocal. In this modernist reimagining, the Fall is not a cautionary tale about sin alone but a profound meditation on the human condition: the inevitability of choice, the birth of self‑awareness, and the burden of knowledge.

Comparison with Von Stuck’s Earlier Version

Von Stuck’s earlier Adam and Eve from 1912 displayed a more decorative approach: stylized foliage, a softer color scheme, and a more playful serpent. The 1920 version, by contrast, is stripped to essentials, reflecting the artist’s evolving aesthetic toward formal reduction and symbolic density. The figures in the later work are rendered with greater solidity and a more neutral palette, indicating von Stuck’s deepening interest in the psychological core of myth rather than its ornamental trappings. This progression mirrors broader shifts in his oeuvre—from richly allegorical canvases to more austere, almost sculptural compositions—underscoring his responsiveness to the changing currents of modern art.

Technical Execution and Conservation

Executed in oil on canvas at a moderate scale, von Stuck’s Adam and Eve demonstrates his mature command of medium. An underpainting in umber likely established the tonal framework, with successive layers of thin glazes and semi‑opaque passages building the subtle flesh tones and the serpent’s luminous blues. The black background may have been applied last, using multiple layers of dark pigment to achieve its depth. Conservation records indicate the painting has retained its color integrity, with periodic cleaning revealing the original vibrancy of serpent and fruit. The canvas’s weave remains visible in places, contributing to the work’s tactile immediacy.

Legacy and Influence

Since its debut, Adam and Eve (1920) has been celebrated as one of von Stuck’s most powerful late works, embodying his Symbolist roots and his stride toward modernist simplicity. It influenced subsequent German painters who sought to balance figuration and abstraction, myth and psychology. The painting continues to resonate in contemporary exhibitions exploring the intersections of art, myth, and human consciousness. Its stripped‑down, evocative portrayal of temptation and choice has inspired artists in various media, from graphic novels to performance art, testifying to the enduring potency of von Stuck’s vision.

Conclusion

Franz von Stuck’s Adam and Eve (1920) stands as a masterful redefinition of a cornerstone myth, merging Symbolist insight with modernist restraint. Through a precise composition, a carefully balanced palette, and an arresting psychological tension, von Stuck distills the Fall into an eternal moment of choice. Eve’s assured offering, Adam’s hesitant reach, and the serpent’s cobalt coil transform two naked bodies into universal emblems of free will and human destiny. In its stark simplicity and profound depth, Adam and Eve invites viewers across generations to confront the paradox of knowledge—that with every step toward enlightenment, we irrevocably leave paradise behind.