Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

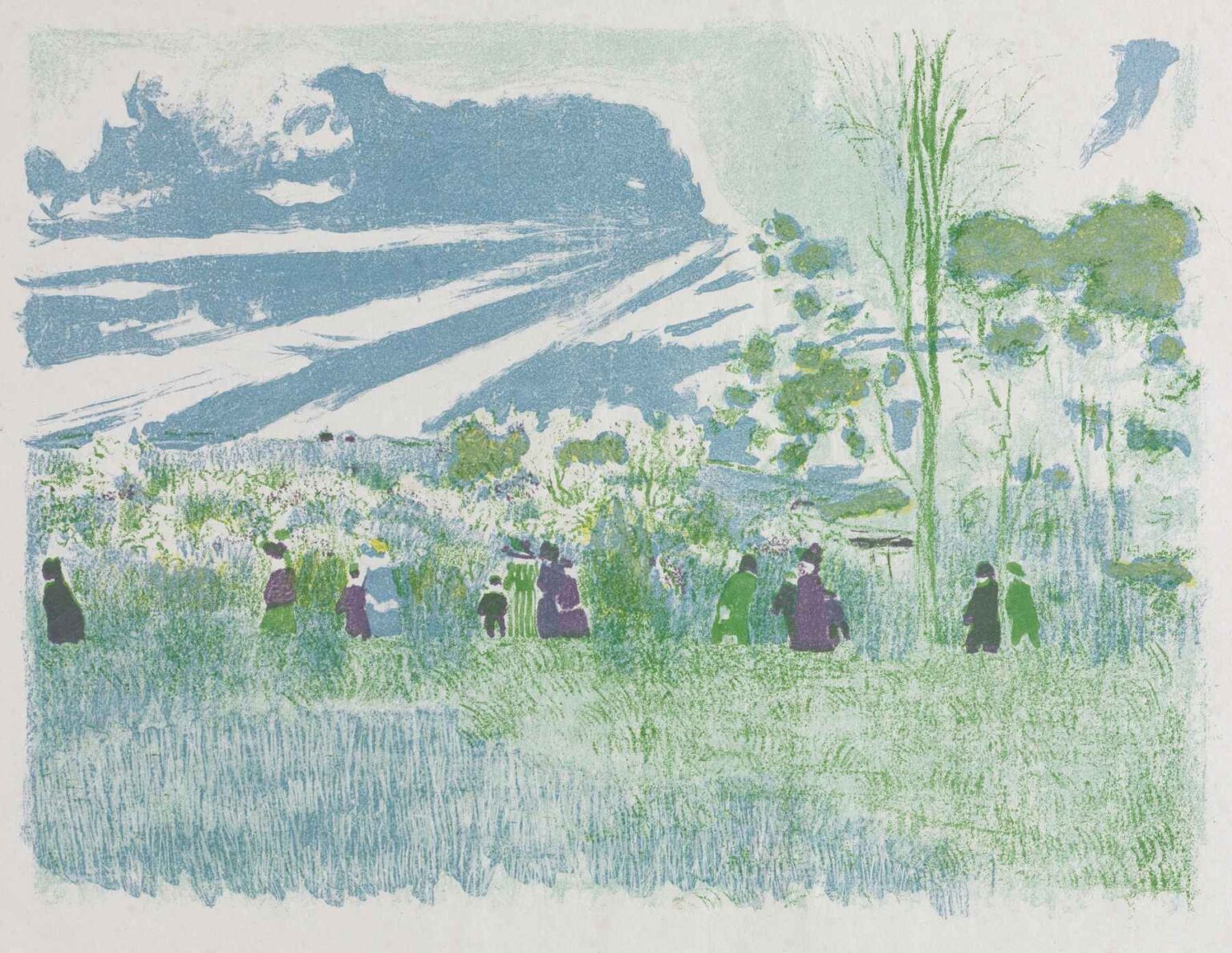

Édouard Vuillard’s Across the Fields (1899) offers an intimate glimpse into a quotidian scene—women and children traversing an open meadow at day’s end—yet it unfolds as something far more profound. Painted at the height of Vuillard’s involvement with the Nabis, this work dissolves boundaries between figure and landscape, interior and exterior, representation and abstraction. Beneath its gentle pastoral veneer lies a carefully orchestrated interplay of flattened space, rhythmic brushwork, and symbolic resonance that elevates the painting into a meditation on time, community, and our inextricable bond with nature.

While many of Vuillard’s contemporaries prided themselves on dramatic mise-en-scènes or bold color experiments, Vuillard excelled at subtler transformations—turning everyday moments into timeless rituals. Across the Fields exemplifies this talent. Its narrative is minimal—a procession moving from left to right—yet through a sophisticated compositional framework and a decorative surface alive with pattern, Vuillard invites viewers to slow down, to notice the whisper of wind through grass, the soft glow of dusk across the sky, and the quiet determination in each footstep. Over the course of this analysis, we will examine how Vuillard’s background, his evolving technique, and the cultural currents of his time coalesced to produce this enduring masterpiece.

1. Artistic and Cultural Context

1.1 Vuillard and the Nabis Movement

By 1899, Édouard Vuillard had firmly established himself as one of the leading exponents of the Nabis—a group of avant-garde painters whose name means “prophets” in Hebrew. In steering away from the fleeting, optical approach of Impressionism, the Nabis looked instead toward symbol, pattern, and the decorative arts. Influenced by the flattened compositions of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, the vibrant synthetism of Paul Gauguin, and the medieval sensibility of William Morris’s tapestries, these artists believed that painting should be a total art form—one that embraced fine art, illustration, and design in equal measure.

Vuillard’s earliest works were intimate interiors: friends posed in richly patterned rooms, their gestures subtle yet charged with psychological nuance. Over time, he came to see no boundary between those enclosed spaces and the world outside. The lush wallpapers and curtains of his domestic scenes gave way to fields and gardens, yet his devotion to surface, texture, and the emotional undercurrents of everyday life remained constant. In Across the Fields, we see a mature synthesis of these strands: the outside world rendered with the attention to surface and decoration once reserved for interiors, while inward feelings of togetherness and quiet reflection are evoked in an open-air ritual.

1.2 Post-Impressionism and Symbolism

The closing years of the 19th century witnessed a fertile overlap of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism across Europe. Post-Impressionists like Cézanne and Seurat had begun to deconstruct optical reality into structural and color relationships. Symbolists, on the other hand, sought to infuse their canvases with dreamlike moods, mythic narratives, and emotional depths. Vuillard occupied a unique position at this crossroads. He borrowed Seurat’s careful attention to color harmony and Paul Gauguin’s idea of the “synthetic” color plane, yet he also embraced Symbolism’s penchant for evocative emptiness and suggestion.

Across the Fields is a testament to this hybrid identity. The gentle gradations of green and lavender recall Neo-Impressionist studies of light, while the hazy far horizon and solitary procession carry a quiet Symbolist pathos. In blending these influences, Vuillard created a work that feels at once grounded in a specific moment and suspended in an almost mythic time.

2. Composition and Spatial Construction

2.1 Flattening the Plane

One of Vuillard’s most radical compositional choices in Across the Fields is his rejection of deep, perspectival space. Instead of leading the eye along receding planes, he presents the meadow as a shallow, nearly two-dimensional tapestry. The grass occupies the lower third of the canvas in a broad expanse of color and texture, while the figures form a low horizon line that gently slopes upward from left to right. The sky, in turn, fills the upper portion with soft washes of cream and blue.

This flattening is characteristic of the Nabis’ embrace of decorative sensibility: each horizontal band—grass, figures, foliage, sky—acts as a patterned frieze. Yet despite this flattened approach, a sense of depth is suggested through variations in color saturation and detail density: the grass strokes become lighter and more spaced out toward the foreground, while the figures, rendered slightly more crisply than the surrounding foliage, momentarily assert a modest degree of relief.

2.2 The Diagonal Procession

While the painting’s overall structure is horizontal, Vuillard animates the scene through a soft diagonal movement. The line of walkers progresses from the lower left corner toward a gently raised midpoint on the right. This diagonal pulse creates a sense of forward momentum, subtly narrativizing an otherwise still tableau. The diagonal slope also connects the human activity with the natural contours of the land and sky—echoed by the faint diagonal curve of distant tree lines and the slanted directions of tall grasses—reinforcing the unity of human and environment.

2.3 Balancing Focus and Freedom

Vuillard strikes a delicate balance between areas of focus and zones of open space. Around each figure or cluster of figures, he concentrates both color and detail—slightly denser brushwork, more defined silhouettes, and hints of distinguishable hats, shawls, and dress patterns. In contrast, the blank expanses of grass to the left and the more ethereal sky above breathe freely, giving the eye space to rest before returning to the human presence. This measured alternation between detail and openness creates a rhythmic visual journey that mirrors the walkers’ measured steps across the field.

3. Color and Brushwork

3.1 A Poetic Palette

At the heart of Vuillard’s visual impact is his carefully tuned palette. Greens range from sunlit apple in the foreground to muted olive in the midground, and finally to bluish sage near the horizon. Soft purples and mauves infuse distant hills and shadows, adding a dreamlike quality to the scene. The sky itself hovers between pale cream and a wash of powder-blue, suggesting the last light of day without resorting to high-keyed spectacle.

Meanwhile, the figures wear subdued but distinct colors—dull violets, dark greens, and hints of rust—that harmonize with the field’s tones rather than clashing. This color economy deepens the sense of community and belonging: the walkers are literally and figuratively clothed in the landscape’s palette.

3.2 Rhythmic Brushwork

Vuillard’s paint handling is characterized by short, myriad strokes that pulse with life. The grass, for instance, is built from hundreds of vertical to diagonal dashes. These individual marks coalesce into an undulating sea of green that suggests both the texture of grass blades and the airflow passing through them. Around the walkers, Vuillard modifies his strokes into tiny crosshatches and curved dabs that indicate folds in fabric, gestures of arms, and hats set at jaunty angles.

This decorative yet dynamic brushwork is the hallmark of Vuillard’s mature style. It invites the viewer closer, rewarding sustained looking with the discovery of innumerable rhythmic lines and color interactions. At the same time, from a distance, these discrete strokes fuse into luminous planes of color, maintaining the composition’s overall harmony.

4. Figures as Emissaries of Mood

4.1 Anonymous yet Resonant

Instead of detailed faces or individualized features, Vuillard opts for silhouette-like renderings of his walkers. Their general forms—upright figures in skirts and shawls, small children trailing behind—are enough to suggest familial bonds or communal routines without anchoring the scene to specific identities. This deliberate anonymity transforms the painting from a documentary snapshot into a universal allegory of human passage.

4.2 Gesture and Gait

Though simplified, the figures’ postures convey subtle emotion. Shoulders incline slightly forward; heads tilt with consideration of where to place the next foot. One woman gently steadies a child, while another appears to glance back or engage in quiet conversation. These gestures, barely sketched yet evocative, generate a sense of shared purpose and mutual support. The human presence is warm and reassuring, yet not overly sentimental—an understated tribute to the small moments of camaraderie that structure daily life.

4.3 Integration with the Meadow

Vuillard never isolates his figures against a blank background; instead, he deliberately allows grass patterns and strokes to cross over their skirts, as if the very meadow is weaving through them. This compositional strategy blurs the divide between people and place. In Vuillard’s vision, humans are not conquerors of the land but participants in its patterns and rhythms. The walkers’ presence does not disrupt the meadow; it merely enacts another layer of its decorative scheme.

5. Symbolism and Thematic Depth

5.1 Journey and Passage

The left-to-right motion in Western art often symbolizes forward movement through time. Here, Vuillard’s procession becomes a metaphor for life’s passage—beginning at the left edge, where unmarked field presages fresh possibility, and advancing toward an ambiguous horizon at right, which suggests the unknown future. Because the horizon is softly blurred, the destination is more a feeling of “what comes next” than a known physical place. This invites viewers to reflect on their own journeys: childhood’s certainty, adulthood’s companionship, and life’s unfolding mysteries.

5.2 Community and Solidarity

By portraying multiple figures moving together, Vuillard celebrates communal unity. Unlike solitary Romantic wanderers, these walkers display a sense of mutual reliance. Their proximity suggests comfort and care, resonating with Symbolist ideals of spiritual unity. The subdued anonymity of each figure underscores that the painting is not about any single individual but about the collective human experience—shared challenges, shared hopes, and shared movement across life’s changing landscapes.

5.3 Nature’s Embrace

Nature in Across the Fields is neither wild nor tamed, but gently suffusing. Grass, foliage, and sky envelop the walkers in an almost maternal embrace. This invites a reading in which nature nurtures and guides them, rather than presenting an adversarial or indifferent force. The painting thus embodies a harmonious vision of humanity in communion with the environment—an ideal that resonated powerfully amid the rapid urbanization and mechanization of late 19th-century Europe.

6. Technique and Materiality

6.1 The Handcrafted Surface

Vuillard’s process likely involved an initial underdrawing—perhaps in wash or chalk—followed by multiple layers of paint applied in small, deliberate strokes. Close inspection reveals glimpses of primer or underlayer in the grass and hills, indicating that Vuillard modulated his chroma through thin glazes as well as thicker, opaque passages. This layered approach yields a luminous depth that changes with viewing distance: from afar, the painting shimmers as continuous color fields; up close, it reveals a complex map of individual brushmarks.

6.2 Scale and Intimacy

At a modest size relative to the giant canvases popular in academic circles of the time, Across the Fields invites proximity. Its dimensions encourage viewers to lean in, to appreciate the tactile quality of each stroke. This intimacy aligns with Vuillard’s commitment to personal, human-scale art—an antidote to the impersonality of industrial mass production. The handcrafted surface becomes an essential part of the painting’s message: that art, like life, is built moment by moment, mark by mark.

7. Legacy and Influence

7.1 Resonance in 20th-Century Art

While Vuillard never achieved the widespread fame of some of his peers, his innovations in flattening space, integrating decorative pattern, and infusing everyday scenes with symbolic charge exerted a subtle but enduring influence. Early 20th-century Fauves such as Henri Matisse drew on his use of luminous color harmonies, while Cubists respected his flattening of planes and rhythmic line. Mid-century artists who explored the boundary between representation and abstraction—Helen Frankenthaler or Richard Diebenkorn, for instance—can trace part of their lineage to Vuillard’s poetic dissolution of form.

7.2 Rediscovery and Modern Appreciation

In recent decades, art historians have reappraised Vuillard’s landscapes, recognizing in works like Across the Fields a bold counterpoint to his interior scenes. The painting’s themes of community, environmental harmony, and temporal passage resonate strongly today, offering a model for art that speaks both to personal memory and to broader ecological consciousness.

Conclusion

Édouard Vuillard’s Across the Fields (1899) stands as a testament to the transformative power of subtlety. Through careful flattening of space, a gently orchestrated procession, a measured yet expressive palette, and surface rhythms that weave figures into the land, Vuillard reimagines a simple walk through a meadow as a universal rite of passage. Human presence and natural form merge in quiet communion, inviting viewers to reflect on the shared journeys that define our lives and on the deep-rooted bonds between community and environment.

Over 120 years after its creation, Across the Fields continues to speak to contemporary audiences—reminding us that the most ordinary moments, when aligned with the rhythms of color, line, and shared human experience, can become portals to reflection, empathy, and a renewed sense of connection with the world around us.