Image source: artvee.com

The Move from Figuration to Pure Ornament

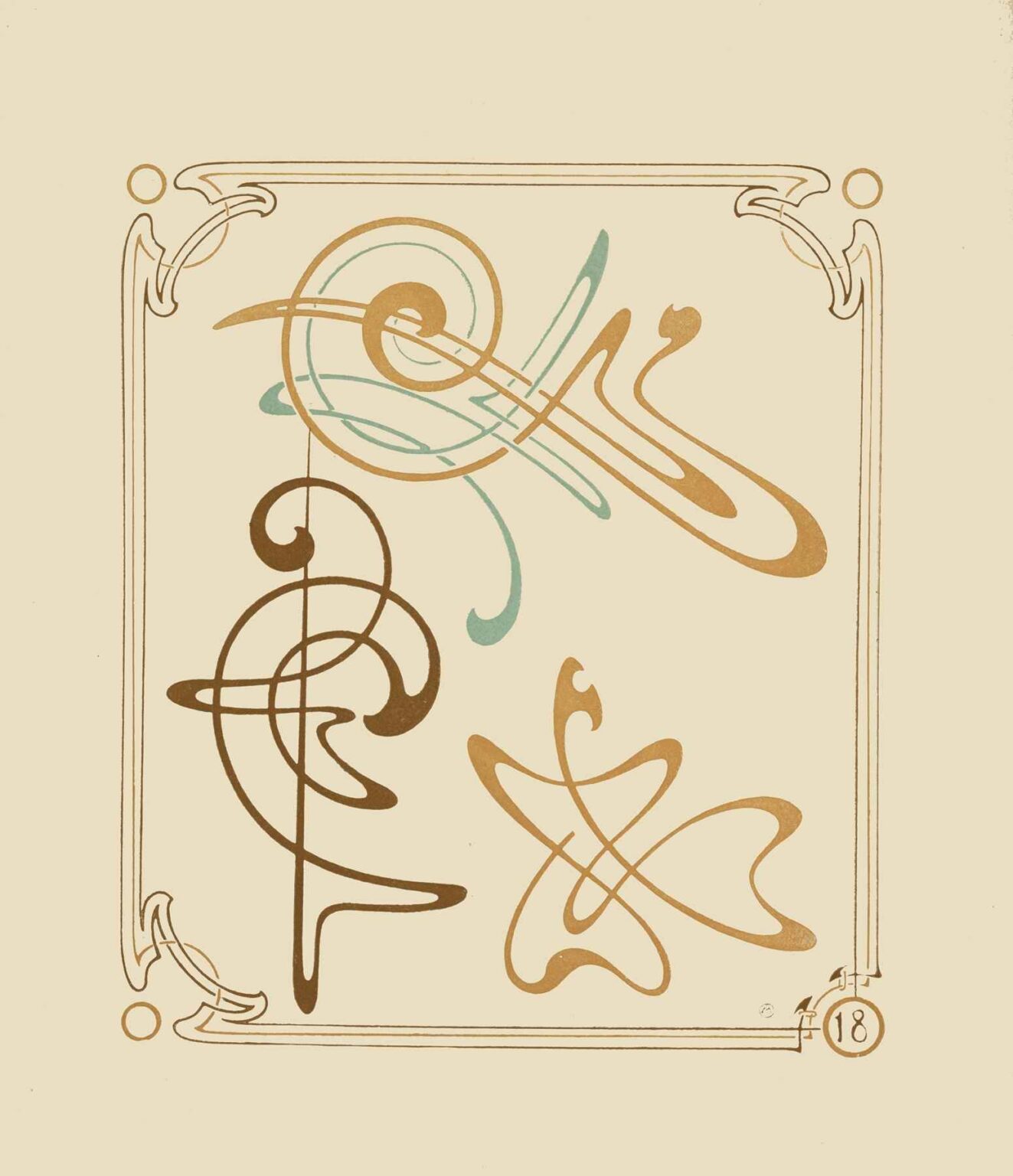

At the height of his Art Nouveau fame, Mucha turned his restless creativity toward the very essence of decoration. “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques,” executed in 1900, marks a striking departure from his legendary figure-based posters. Here he explores ornament as autonomous subject matter. Without narrative or human form, the sheet of four motifs invites close study of line, rhythm, and balance. The arabesques—historically derived from Gothic and Moorish patterns—become living gestures, liberated from representational context. Mucha’s decision to frame these motifs within a simple double-line border underscores the seriousness of his inquiry: ornament itself, he seems to proclaim, can sustain the viewer’s attention and evoke pure aesthetic pleasure.

Historical Context: Ornament at the Dawn of a New World

The turn of the century found Paris ablaze with decorative innovation. The 1900 Exposition Universelle celebrated ornamental art alongside industrial modernity, and designers championed the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art uniting fine and applied arts. Mucha, fresh from his success with theatrical posters, aligned himself with this movement by experimenting in pattern design. “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques” reflects an era eager to escape academic tradition and to forge new decorative vocabularies. By isolating the arabesque form, Mucha participates in a broader continental dialogue with counterparts in Vienna, Glasgow, and Brussels, each seeking to elevate ornament to the status of pure art.

Composition and Spatial Rhythm

The composition unfolds as an elegant grid of four arabesque studies within a thin gold frame. The sheet’s negative space—the unadorned cream ground—allows each motif room to breathe. The upper motif, sweeping and expansive, commands the viewer’s gaze first. Its broad loops and sweeping curves evoke acanthus leaves and ocean waves entwined. Below, the two lower motifs offer contrasting energies: the left flourish rises in a single vertical curve, like a budding vine, while the right motif interlaces multiple loops into a compact star shape. A smaller accent form echoes the upper motif’s spiral. These variations in scale and direction create a dynamic conversation across the page, as the eye moves from one arabesque to the next and then returns to the frame’s restrained flourish.

Calligraphy of Line and Gesture

At the core of Mucha’s experiment lies his calligraphic mastery. Each arabesque is drawn with a lithographic crayon that conveys both strength and subtlety. The thickest strokes anchor key curves, while hairline connections trace delicate offshoots. At pivot points, the artist allows line density to build, imparting visual weight where the motif must turn or spiral. Elsewhere, the line thins to a whisper, suggesting tendril-like extensions. This modulation of line weight and speed transforms static patterns into animated gestures, as if each arabesque were mid-breath, mid-growth. The lithographic process—stone drawing, inking, pressing—captures this nuance, rendering line “alive” on the paper’s surface.

Palette as Poetic Accent

Mucha confines his palette to three principal hues—warm gold, deep brown, and muted green—each chosen for its evocative resonance. Gold, shimmering in the upper motif, recalls precious metal filigree and the gilded frames of medieval manuscripts. Brown, used in the vertical flourish, grounds the composition with earthy depth. Green, reserved for the smallest grid accent, evokes living vegetation. These colors, applied sparingly, draw attention to formal interplay rather than chromatic excess. They also create subtle hierarchies: gold signals primary forms, brown secondary, and green tertiary. The restrained palette imbues the sheet with quiet elegance, allowing the arabesques’ rhythmic complexity to take center stage.

The Frame as Extension of Ornament

Mucha’s double-line frame does more than contain the motifs; it echoes them. Each corner features a delicate flourish, a miniature arabesque that hints at the larger studies within. The outer band anchors the composition to the page’s edge, while the inner line sets a boundary for decorative exploration. Between the bands, the motifs seem free to expand, their curves nearly touching but never overlapping the frame. This interplay underscores the frame’s dual role as both limit and stage, reinforcing the notion that ornament can flourish best when given defined space in which to breathe.

Discipline and Variation in Ornament

One of the sheet’s most remarkable aspects is its disciplined approach to variation. All four motifs derive from the same formal vocabulary—spirals, loops, and offshoots—but none repeats another. Mucha demonstrates how infinite variation can spring from a simple set of curves. The vertical flourish, though minimal, captures the upward thrust of budding life; the compact star motif suggests the blossoming of multiple stems; the expansive spiral weaves in and out like living water; the small accent motif provides a poetic sigh of line. Together, they model a principle at the heart of Art Nouveau: that decoration is not mere repetition but an organic, generative process.

From Sketchbook Study to Applied Design

Though the sheet stands alone as a fine-art work, it likely originated as a pattern study within Mucha’s studio. His assistants and fellow craftsmen would use these arabesques as templates for larger projects: stained glass windows, textile prints, furniture inlays, or architectural friezes. The motifs’ adaptability—scalable, reversible, and combinable—renders them ideal for practical application. Mucha’s presentation of several variations on a theme serves as a design manual, guiding artisans on how to rotate, invert, or repeat forms to suit diverse surfaces. In this way, “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques” bridges the gap between high art and craft, fulfilling the era’s call for unity across creative disciplines.

The Arabesque in Art Historical Perspective

The arabesque motif traces back to Islamic and Moorish ornament, where stylized foliage and interlacing vines fill surface entirely. Renaissance and Baroque designers later adopted these forms for European contexts, decorating book bindings, metalwork, and interior plasterwork. Mucha’s study arrives at a moment when designers reclaimed the arabesque as a modern symbol of organic unity. His approach—distilling curves to their essence—resonates with contemporaries like Charles Rennie Mackintosh in Glasgow or Hector Guimard in Paris. Yet Mucha’s arabesques retain a personal lyrical flair, revealing his belief that ornament must express the living pulse of nature rather than rigid mathematical formula.

Technical Mastery of Lithography

Creating this sheet demanded exceptional technical skill. Mucha executed his arabesques directly on lithographic stones using greasy crayons of varying hardness. Each crayon stroke translated into a precise ink line on paper, capturing the calligraphic energy of the original gesture. Distinct stones carried the gold, brown, and green inks, each requiring exact registration to align with the line work. Rarely did early lithographs achieve such clarity of multi-color, multi-stone printing; “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques” demonstrates Mucha’s collaboration with the best printers of his day. The result is a work that feels both spontaneous and immaculate—inked with visible fervor yet pressed with mechanical precision.

Influence on Decorative Arts and Beyond

Though overshadowed by Mucha’s theatrical posters in popular memory, his abstract ornament studies quietly shaped the decorative arts of the early twentieth century. Florists, jewelers, wallpaper designers, and interior decorators drew upon his motifs, adapting arabesques into commercial products. The emphasis on organic forms and sinuous line in “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques” anticipated the sweeping curves of Art Nouveau ironwork and the flowing typefaces that would define the period’s graphic design. Even later Modernists would reference these motifs, recognizing in Mucha’s arabesques a bridge between historic ornament and the abstraction that art would soon fully embrace.

Reception and Legacy

Collectors and critics of the early 1900s admired the sheet for its formal rigor and decorative promise. While few prints sold compared with his poster editions, “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques” found homes among design-savvy patrons and institutions promoting decorative art education. Today, art historians regard it as a pivotal demonstration of Mucha’s theoretical engagement with ornament—proof that the legendary poster artist had broader creative ambitions. In exhibitions tracing the evolution of Art Nouveau, the arabesque studies often appear alongside architectural drawings and furniture designs, showcasing their influence across disciplines.

Conclusion: The Living Line Realized

In “Abstract Design Based on Arabesques,” Alphonse Mucha elevates ornament to the highest levels of artistic inquiry, proving that line alone can convey vitality, balance, and poetic depth. Through four distinct motifs, he demonstrates how sinuous curves and disciplined variation give rise to endless decorative possibilities. The work stands as both a fine-art exploration and a practical design resource, embodying the Art Nouveau ideal of unity between art and everyday life. More than a historical curiosity, Mucha’s arabesque sheet invites contemporary viewers to rediscover the living potential of line—an inspiration for designers, artists, and appreciators of beauty in its purest, most abstract form.