Image source: wikiart.org

A Small Etching With Monumental Presence

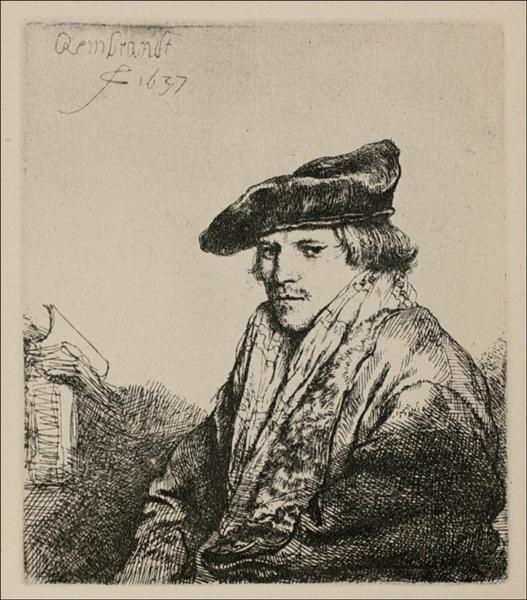

Rembrandt’s “A Young Man Seated, Turned to the Left” from 1637 is a masterclass in how an artist can compress psychological depth, atmospheric space, and tactile richness into a print scarcely larger than a hand. The sheet shows a youth in three-quarter view, body angled toward the left margin, face rotated slightly back toward us, his gaze steady and reserved. A soft cap crowns his hair, a fur-lined cloak wraps his shoulders, and a loose glove or cuff spills over the wrist in the lower left. At the upper left, the artist’s signature and date anchor the image within a precise historical moment. The whole scene breathes with an intimacy that characterizes Rembrandt’s best small portraits: nothing theatrical, everything considered.

Etching As Thinking Aloud

The technique is etching, and likely a touch of drypoint in the darker, velvety passages. Unlike engraving, which demands forceful, predetermined incisions, etching lets the hand move with the freedom of drawing. Rembrandt exploits that freedom to think aloud across the copper. Lines switch temperament as they move from face to fabric, from contour to shadow. In the background, short parallel hatches and crosshatches create a gently vibrating darkness that sets off the head and shoulders. Around the mouth and nose, the lines shorten, thin, and breathe, as if the tool tip itself were inhaling between marks. The technique does not merely record a likeness; it narrates the artist’s attention as it moves from general silhouette to specific incident.

The Architecture Of The Pose

The sitter’s pose is remarkably architectural. His torso forms a shallow triangle tapering toward the waist, with the broad base resting along the lower edge of the plate. The slight pivot toward the left gives the body weight and direction, while the head’s counter-turn returns our attention to the eyes. This oppositional geometry—body away, face toward—creates a low, steady drama without a single exaggerated gesture. The leftward orientation also activates the surrounding space. The dark wedge of background at left reads almost like a column or piano, a vertical element that compresses the sitter’s figure into the foreground and deepens the illusion of volume.

Costume As Topography

Rembrandt treats clothing as a terrain to be explored. The cap is a compact landform with a ridge of compressed fabric near its crown and a softer bulge above the brow. The fur lining is rendered through short, splayed strokes, a vocabulary of marks that shift direction like grass in wind. These textural decisions do more than dazzle; they guide the eye along the garment’s edge and back to the face. The cloak, cut generously, flows in a series of diagonal folds that echo the sitter’s leftward turn, amplifying the sense of movement contained within repose. It is important that the cloak is not ostentatious. The image honors warmth and utility rather than display, and in that restraint the sheet locates a quiet nobility.

Light That Rises From The Page

There is no painted glow here, yet the print has a palpable luminosity. Rembrandt achieves this by orchestrating zones of dense bite against areas where the white of the paper is allowed to breathe. The background darkens as it approaches the sitter’s contour, like a cloudbank passing behind a hill. The face emerges from this tonal envelope with a subtle raking light from the left, which catches the cheekbone and the ridge of the nose, dips into the shadow beneath the lower lip, and touches the collar’s edge. This orchestration is all the more impressive because it is built from hatched lines rather than brushes. The print seems to discover light within its own network of strokes.

The Signature As Threshold

In the upper left, “Rembrandt f 1637” operates not as a decorative flourish but as a threshold into the image’s world. The letters float in unetched paper, the lightest area on the sheet, set against the darker backdrop of the sitter’s cloak and the murky architecture at left. Their placement is psychologically astute. Signature and date hover near the sitter’s line of sight, as if artist and subject share a corner of the studio where time and identity are quietly noted before work resumes. The inscription’s openness also balances the composition, preventing the upper field from becoming oppressively dark.

A Studio Corner That Feels Lived In

Rembrandt suggests an interior without littering the plate with props. At the far left, angled lines hint at a table edge or balustrade. Behind the sitter, a slope of hatch marks falls away into a shadow that could be a curtained recess or simply the ambient darkness of a modest room. The ambiguity is deliberate. The fewer the specifics, the broader the resonance. We recognize the feeling of a corner where one sits to rest, to warm oneself, to listen, to be drawn. The studio becomes any room we have known that is more about presence than ornament.

The Psychology Of A Half-Smile

Rembrandt’s portraits often hinge on small adjustments of the mouth and eyes. Here the youth’s lips gather at the corners into something between a smile and a guarded line, while the lower eyelids are slightly raised as though he has been addressed and is forming a reply. That half-smile introduces a conversation into the stillness of the pose. It refuses either flattery or severity, giving the sitter a human complexity beyond simple typology. This is not a generic young man; it is this young man, in a particular mood, at a particular hour, with a particular painter in front of him.

Unknown Sitter, Known Humanity

The sitter’s identity is uncertain. He could be a studio assistant, a friend, a client of modest means, or a model loosely summarized. Rembrandt’s practice across the 1630s includes many genre-like figures who hover between portrait and study. That ambiguity is productive here. Without the biographical anchor of a famous name, we attend to character rather than status. The result is a democratic image, part of a broader seventeenth-century Dutch culture that found value in ordinary faces and private moments.

Paper, Ink, And The Breath Of Printing

The object we see today is likely one of several impressions pulled from the copper plate. Each impression can vary depending on inking, pressure, and the presence of plate tone—the film of ink left deliberately on the surface to deepen atmosphere. Rembrandt was a virtuoso manipulator of these variables. The softly smoked air around the sitter’s head may be the result of such plate tone, which gathers in the plate’s recesses and wipes more thinly on the high areas near the signature. The tactile qualities of the paper also matter. Slight tooth catches ink and gives hairsbreadth edges to lines, creating a print that appears to breathe when viewed closely.

The Economy Of The Spectator’s Imagination

One of the most striking features of the plate is how much Rembrandt leaves out. The hand at lower left is indicated with a few suggestive strokes; the rest is elided into the dark fall of the cloak. The hat’s rim is broken rather than continuous. The left edge of the body dissolves into the surrounding tone. Far from a deficiency, this economy is an invitation to the viewer’s imagination to supply what is missing. The print achieves fullness through suggestion, a technique that puts the spectator to work and thus deepens involvement in the image.

A Conversation With Earlier Self-Portraits

The format and pose recall Rembrandt’s own self-portraits and self-studies in etching from the early to mid-1630s. Those plates often show the artist turned in profile or three-quarter, testing expressions, hats, and lighting schemes. By placing a different sitter into a familiar structure, Rembrandt both reuses and refreshes a compositional solution. He knows exactly how to balance the mass of a cap against the expanse of a cloak, how to let a shoulder tilt set the rhythm for the plate. The effect is like listening to a musician who returns to a beloved key and finds a new melody.

The Market For Small Prints

The 1630s were boom years for prints in the Dutch Republic. Collectors assembled albums; merchants and craftsmen could afford sheets that wealthy patrons commissioned in paint. Small etchings such as this one fit the market perfectly. They could be acquired singly, pasted into books, and handled in intimate settings where conversation paired with close looking. Rembrandt’s ability to produce prints that felt both spontaneous and finished helped him reach audiences beyond those who could commission portraits on canvas. The intimacy of scale is not a limitation; it is a deliberate social strategy.

The Sitters’ Social Signals

Clothing and bearing communicate class with subtlety. The fur lining and capacious cloak suggest comfort and some means, though not lavishness. The cap is practical rather than ostentatious. The sitter’s posture implies confidence held in reserve rather than displayed. Rembrandt is careful to honor dignity without embellishment. The young man could be a clerk or a prosperous artisan; the ambiguity protects the timelessness of the image. We read character where badges of rank might have diverted us into cataloging status.

The Grammar Of Rembrandt’s Line

Rembrandt’s etched line has grammar and cadence. It thickens to emphasize weight, thins to let light through, crosses itself to create a darker vowel of tone, and ends with a slight tremor that reads as softness. In the face, short, shallow bites form consonants around the nose and mouth; in the cloak, longer strokes function as flowing clauses. The background, with its web of dark hatches, is a paragraph in which the syntax slows and the eye rests before returning to the figure. By thinking of line as language, we recognize why the print feels articulate even where description is sparse.

Time, Attention, And The Moment Of Being Looked At

Portraiture is an exchange of attentions: the sitter’s willingness to be seen and the artist’s capacity to look with care. This plate crystallizes that exchange. The young man’s gaze meets ours sidelong, acknowledging our presence without yielding center stage. The artist returns the courtesy by refusing to stereotype his features or dramatize his setting. What remains is a mutual pause in time, the kind of quiet minute that often passes unnoticed in life yet becomes unforgettable in art. The plate teaches us how to value such minutes.

The Edge As A Site Of Drama

The left edge of the plate is unusually active. It hosts the signature, a wedge of still-uncertain architecture, and the invisible margin toward which the sitter turns. That cluster of elements charges the boundary with energy. The viewer senses that something lies just beyond our sight—a table, a window, a person who has just spoken. The edge becomes a hinge on which the present moment turns. By energizing the margin rather than the center, Rembrandt avoids theatrical centrality and achieves a more naturalistic rhythm.

The Young Man As A Type Of Thought

Look long enough and the sitter reads less as a social individual than as a form of thinking. His eyes do not dart; they settle. His lips do not press; they soften. The pose suggests someone who listens before he speaks, who weighs a remark before answering. Rembrandt had a gift for making inwardness visible without resorting to allegory. Here the furrow of the cloak, the tilt of the cap, and the slight shadow below the lower lip collect into a portrait of attention itself. The image feels honest because it grants the sitter a private interior while sharing just enough of it with us.

Variations, States, And The Pleasure Of Comparison

Like many of Rembrandt’s prints, this plate may exist in multiple states—versions of the image altered on the copper and printed at different times. Collectors delight in comparing the subtle changes: a deepened shadow here, a strengthened contour there, a newly wiped plate tone that shifts the atmosphere. Such variations remind us that the print is not a fixed object but a living practice. Rembrandt’s studio is audible in the trial and revision, the willingness to re-enter a plate to pursue a more convincing light or a more persuasive weight to the cloak.

The Tenderness Of Imperfection

A few lines go astray. The contour around the shoulder softens into the background more quickly than strict modeling would require. The hand is abbreviated. Yet these so-called imperfections are crucial to the print’s tenderness. They keep the image from becoming a polished emblem. They preserve the trace of a person working in real time, trusting the viewer to prefer vitality over finish. That trust dignifies us as spectators, making us partners in the completion of the image.

A Modern Intimacy Across Centuries

The image retains a startling freshness. Its uncluttered background, frank lighting, and preference for economy over ornament feel at home in modern sensibilities. One can easily imagine this young man seated in a café or studio today, his posture and quiet attention unchanged. This transhistorical intimacy is the gift of Rembrandt’s approach. By avoiding period theater, he meets humanity at a level that outlives fashions.

The Quiet After The Plate Is Lifted

Consider the instant when the press releases the freshly inked paper from the copper. The printmaker lifts the sheet; the image, reversed from the plate, appears for the first time as a mirror of the drawing. In that moment the young man’s presence enters the world. The process matters because it aligns with the content: the slow bite of acid, the careful inking, the pressure and release, the reveal of the face. All of it mirrors the rhythm of a conversation in which a person gradually shows himself. The craft and the psychology rhyme.

A Last Look

Return to the eyes. They are not overly darkened; Rembrandt resists the sentimental bright point that would literalize liveliness. Instead, the eyes are integrated into a mask of tone across the face, emerging from and receding into the same network of lines that define the cheek and brow. That integration is why the image endures across repeated viewings. It never forces a single “read.” It makes space for a range of moods—thoughtful, reserved, observant, perhaps even amused. Each encounter with the print becomes a new sitting.