Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

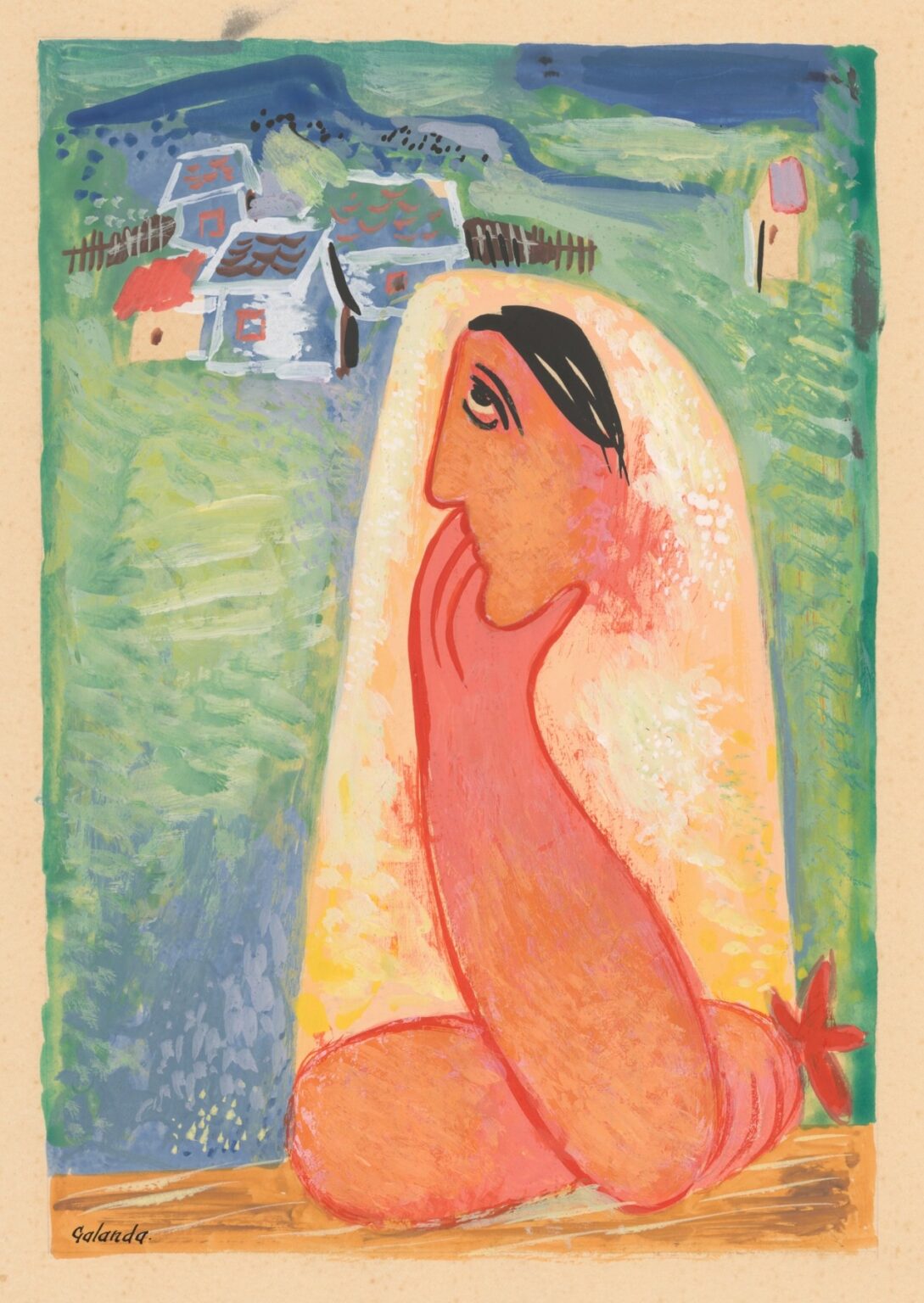

In A Villager (1938), Mikuláš Galanda captures the timeless dignity and quiet introspection of rural life through a masterful fusion of modernist abstraction and expressive color. The gouache and ink composition presents a single seated figure—rendered in warm oranges and pinks against a luminous background of greens and blues—set before a faint cluster of village houses. While the villager’s simplified form evokes universal human qualities, the distinctive palette and rhythmic brushwork root the work firmly within Galanda’s unique visual language. This analysis will explore the painting’s historical context, compositional strategies, color harmonies, symbolic resonances, and technical execution to reveal how Galanda transforms a humble subject into a profound meditation on identity, place, and the bonds between humanity and landscape.

Historical Context

Painted in 1938, A Villager emerges at a moment of intense social and political flux in Europe. Czechoslovakia, established barely two decades earlier, faced mounting external pressures as neighboring powers eyed its borders. Internally, rural communities were experiencing both the benefits and dislocations of modernization: mechanized agriculture brought efficiency but also threatened traditional ways of life. In this charged atmosphere, artists such as Mikuláš Galanda turned to the figure of the villager as a repository of cultural continuity and moral strength. By choosing to depict a solitary rural inhabitant rather than an urban or aristocratic subject, Galanda asserts the enduring value of simple, local existence against the backdrop of geopolitical uncertainty.

The Artist and His Vision

Mikuláš Galanda (1895–1939) was a leading figure in Slovak modernism, renowned for his ability to synthesize international avant‑garde influences—Cubism’s geometric rhythm, Fauvism’s bold coloration, and Expressionism’s emotive power—into a distinct national idiom. Having studied in Budapest and Prague, he returned to Bratislava to co‑found influential artist groups such as Vara and Devětsil, which championed progressive forms of art and cultural renewal in the young republic. By the late 1930s, Galanda’s work had evolved towards an economy of means and a focus on graphic clarity. A Villager exemplifies this mature period, where his mastery of gouache and ink yields both glowing fields of color and incisive contour lines.

The 1930s and Rural Identity

During the 1930s, Czechoslovakia’s rural landscape became a potent symbol of national identity. Folk traditions—costume, festivals, architectural vernacular—were celebrated as authentic expressions of the people, in contrast to the perceived artificiality of urban cosmopolitanism. Intellectuals and artists promoted ethnographic research, often collecting songs, stories, and crafts from village communities. Galanda’s decision to depict a villager resonates with this broader cultural valorization. Yet his approach transcends mere folkloric documentation; he imbues his subject with modernist abstraction and psychological depth, inviting viewers to engage with the universal human experiences embodied in the figure.

Compositional Strategies

A Villager is structured around a commanding vertical figure that occupies the right two‑thirds of the composition. The sitter is seated in profile, her arm resting on bent knees, head supported by a hand in a gesture of thoughtful repose. To the left, a loosely rendered grouping of houses and fences appears in the distance, while a lone outbuilding hints at the wider landscape. Galanda flattens spatial depth through overlapping color fields and minimal perspective cues: the roofs of the houses recede through shifts in hue rather than converging lines. This compositional balance—between the monumental figure and the subtle background—underscores the intimate bond between individual and environment.

Use of Line and Contour

Line in A Villager serves to both define form and inject gesture into the static pose. Galanda employs fluid black ink strokes to outline the figure’s profile, arm, and legs, while using thinner, more tentative marks to indicate facial features such as eyes and hair. The roofs and walls of the houses are drawn with similar decisive strokes, tying human presence and architecture into a unified graphic system. Within larger color zones, short hatch strokes and scumbles enliven the surface and suggest texture—the roughness of cloth, the grain of wood, or the mottled patches of earth. Through this interplay of bold contour and subtle internal pattern, Galanda achieves a harmonious dialogue between drawing and painting.

Color Palette and Emotional Tone

The painting’s color scheme centers on a radiant blend of oranges, pinks, and yellows for the villager, set against a cooler landscape of greens and blues. This warm‑cool contrast imbues the figure with an inner glow, suggesting resilience and vitality even amid uncertainty. The surrounding greens—ranging from verdant to teal—are applied in expressive brushstrokes that evoke rolling fields or dense meadows. Above, a deep band of blue hints at either distant mountains or the expanse of sky. Galanda’s use of pure, unmodified pigments recalls Fauvist thermatics, yet here the hues carry psychological weight: the warm tones speak of human warmth and rootedness, while the cooler zones suggest the encompassing embrace of nature.

Treatment of the Figure

Although stylized, the villager’s anatomy remains convincing in its proportions and posture. The sitter’s bent knees and relaxed arm convey physical comfort, while the head’s slight tilt and the hand’s touch to cheek evoke introspection or perhaps quiet vigilance. Galanda deliberately simplifies anatomical detail—omitting clothing folds and background clutter—to emphasize the essential human form. The resulting figure becomes an archetype rather than a portrait of a specific individual. This universality allows viewers from diverse backgrounds to project their own experiences of rural life, solitude, or contemplation onto the figure, making A Villager both personal and collective.

Expression and Gaze

One of the painting’s most striking features is the villager’s eye, rendered in black ink with a sharp almond shape and a gaze directed slightly downward. This expression suggests thoughtful observation of the world beyond the canvas, as though the sitter contemplates her own place within the village scene. The eye’s dark outline and stark white pupil create a focal point that draws viewers into the interior realm of the figure’s mind. By giving the villager such a penetrating look, Galanda affirms the subject’s agency and dignity, countering any Romantic notion of the rural folk as naive or passive.

Landscape as Psychological Space

The background, though superficially a depiction of village houses and fencing, functions more as a psychological space than a literal panorama. The loosely painted greens suggest fields, meadows, or enclosed garden patches, but their flat application and gestural texture evoke emotional states—tranquility, unrest, or the ebb and flow of rural rhythms. The houses, isolated and nearly abstracted, float within this emotional topography, reinforcing the villager’s connection to her environment while also underscoring her solitude. Through this evocative landscape, Galanda transforms rural setting into an extension of the sitter’s inner life.

Symbolism of Rural Architecture

The cluster of houses and picket fences carries symbolic weight as markers of shelter, community, and continuity. Their simple geometric shapes—rectangles for walls, triangles for roofs—evoke architectural vernacular across Central Europe. Yet Galanda abstracts these forms sufficiently to suggest that they stand for more than physical dwellings: they symbolize the networks of family, tradition, and collective memory that sustain the individual. The lone outbuilding to the far right serves as a visual echo of the main cluster, reinforcing the idea of dispersed yet interconnected communities across the countryside.

Negative Space and Framing

The generous margins of bare paper surrounding the painted rectangle function as a visual breathing room, isolating the composition from any external clutter. This framing technique, found often in Galanda’s graphic works, accentuates the painting’s constructed quality and alerts viewers to its artifice. At the same time, the empty borders create a sense of quiet contemplation, as if the scene can be rightly appreciated only in deliberate solitude. The contrast between the textured interior and the smooth paper margins further heightens the sense of the villager as enclosed within her own mental and physical landscape.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

A Villager draws viewers into its quiet drama through the tension between stillness and implied narrative. The sitter’s repose invites empathy: one senses both the comfort of rootedness and the weight of responsibility that comes with stewardship of land and tradition. The painting’s restrained gestures—hand to face, downward gaze—encourage viewers to inhabit the villager’s reflective state. Rather than dictating a precise story, Galanda offers a potent emotional palette: pride in rural identity, melancholy at the passing of old ways, and the steadfast calm of those who continue life’s rhythms amid change.

Technical Mastery of Gouache and Ink

Galanda’s adept handling of gouache is evident in the painting’s luminous color fields. The opaque quality of the medium allows vibrant pigments to sit atop the paper ground, creating a rich, matte surface. Visible brushstrokes—scumbled layers, directional marks—lend tactile energy to the fields of green and blue. The ink contours, by contrast, are crisp and flat, delineating figure and structure with unwavering precision. This duality of painterly gesturality and graphic clarity exemplifies Galanda’s belief in the synergy between painting and drawing, showcasing his technical versatility and his exacting control over multiple media.

Comparison with Earlier Works

When contrasted with Galanda’s earlier Fauvist landscapes and Cubist experiments of the mid‑1920s, A Villager stands out for its pared‑down palette and heightened focus on human presence. In earlier canvases, vibrant color often overshadowed figurative detail, and spatial rhythms echoed architectural fragmentation. Here, Galanda distills those concerns into a more unified vision: color remains expressive yet subdued, and line replaces plane as the primary structural agent. This evolution mirrors broader modernist trajectories toward synthesis and refinement, positioning A Villager as a pivotal bridge between exuberant experimentation and mature clarity.

Cultural Significance and National Identity

By depicting a solitary rural inhabitant, Galanda participates in a broader cultural movement that sought to define Czechoslovak identity through folk traditions and peasant archetypes. Unlike nationalist propagandists who romanticized the countryside, Galanda’s treatment is neither sentimentally idealized nor dismissively folkloric. Instead, he respects the villager’s autonomy and inner complexity, suggesting that modern nationhood rests not on mythic nostalgia but on moral integrity and individual dignity. In this light, A Villager becomes a quietly subversive statement: the true strength of a nation lies in the thoughtful resilience of its ordinary people.

Feminist and Social Readings

Although the sitter’s gender is not explicitly defined, many interpret A Villager as depicting a woman—possibly a mother or caretaker—given the nurturing associations of rural domestic roles. The subject’s dignified isolation and intellectual poise challenge stereotypes of rural women as uneducated or bound by tradition. By portraying the villager as contemplative and aware, Galanda underscores women’s agency in shaping both family and community life. This subtle feminist reading aligns with interwar discussions in Czechoslovakia about expanding educational and civic rights for women, suggesting that female villagers possess not only physical labor but also intellectual and moral leadership.

Reception and Legacy

Though Mikuláš Galanda’s untimely death in 1939 curtailed his career, A Villager and related works became cornerstones of Slovak modernism. His refined use of gouache and ink influenced a generation of graphic and painting practitioners, who admired his synthesis of international styles and local themes. Exhibitions of Galanda’s work in the late twentieth and early twenty‑first centuries have highlighted A Villager as an emblem of thoughtful national art—rooted in local realities yet conversant with global modernist trends. Today, the painting continues to be studied for its formal innovation, emotional depth, and nuanced cultural commentary.

Conclusion

In A Villager (1938), Mikuláš Galanda achieves a graceful convergence of modernist abstraction, expressive color, and profound humanism. Through a composition that balances commanding figure and evocative landscape, and through a palette that harmonizes warm flesh tones with cool natural hues, he transforms a simple rural subject into a resonant meditation on identity, resilience, and the passage of time. Galanda’s technical mastery—his interplay of gouache fields and ink contours—imbues the painting with both structural clarity and emotional warmth. As viewers engage with the villager’s thoughtful pose and penetrating gaze, they are invited to reflect on their own ties to place and tradition, and on the universal dignity found in everyday lives.