Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

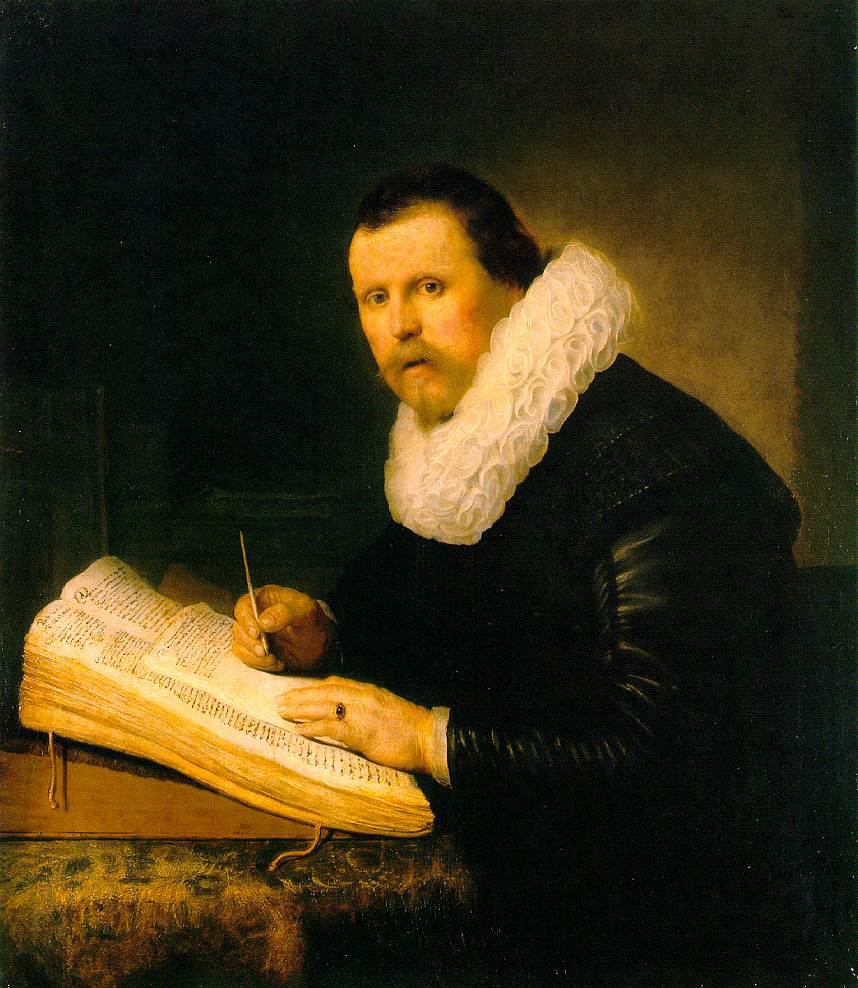

Rembrandt’s “A Scholar” from 1631 is a concentrated meditation on intellect, labor, and presence. A seated man turns from his monumental book, his quill momentarily suspended while he meets the viewer’s gaze. The face, hands, and illuminated pages gather the light, while the surrounding room recedes into a hushed atmosphere. With the simplest of ingredients—a figure, a desk, and a book—Rembrandt crafts a drama of thought caught in mid-flow. The painting belongs to his early Amsterdam period, when he was refining the luminous chiaroscuro and psychological intimacy that would define his work for decades.

The Historical Moment And The Image Of Learning

In the Dutch Republic of the 1630s, scholarship was not an abstraction; it was a public virtue with economic and civic value. The burgeoning merchant culture needed jurists, notaries, theologians, physicians, bookmen—professionals whose authority was grounded in literacy and record-keeping. This image channels that culture’s admiration for learned work. It is not a university allegory with classical props; it is a portrait-like study of a working intellectual. The sitter’s ruff and sober black attire place him squarely within the social idiom of the time, balancing restraint with prestige.

A Composition Built On Triangles And Sightlines

Rembrandt organizes the scene as a set of interlocking triangles. The angled book forms the first, its lower edge running parallel to the table while the upper leaf rises toward the figure’s chest. The scholar’s torso and head shape a second triangle that points toward the source of light. Between them, the writing hand becomes a bridge that carries the viewer from page to person. The gaze, turned outward and slightly upward, arcs back to the lamplit pages, creating a circular path that keeps the eye moving between thought and its inscription. Nothing in the composition is accidental: the cropped table, the small wedge of shadow behind the sitter, and the alcove across the back wall quietly stabilize the central action.

Chiaroscuro As Theater Of The Mind

Light enters from the left, striking the parchment and leaping to the scholar’s forehead, nose, and cheek before coming to rest on his hands. The effect is neither harsh nor diffuse; it is decisively placed to declare what matters. The background, by contrast, is an even dusk that grants privacy to the act of reading and writing. This calibrated chiaroscuro does more than model form—it shapes narrative. The glow on the page becomes a metaphor for insight, while the gentle fall of shadow across the eyes suggests concentration temporarily suspended in order to acknowledge the viewer.

The Monumental Book And The Craft Of Reading

The book dominates the foreground like a low altar to learning. Its thickness, warped edges, and braided bookmarks convey age and use. Rembrandt renders the leaves with a mixture of thin glazes and dry, dragging strokes, allowing the texture of the canvas to read as fibrous paper. The text itself, glimpsed in tight rows, is less about legibility than about the optical impression of script; the painter simulates the density of information rather than each letter. The book’s angled placement turns it into a luminous reflector, bouncing warm light back onto the scholar’s hands and ruff. In visual terms, the codex is both object and light source—an apt metaphor for knowledge.

Gesture, Pause, And The Psychology Of Interruption

The scholar does not pose; he pauses. The quill is lifted just above the paper, and the left hand spreads the page, preventing it from sliding closed. This is a working gesture, practical and elegant. The parted lips and intent stare imply a thought crossing the threshold from interior to exterior. Rembrandt excels at such liminal moments—when the mind tips into speech or inscription. The painting’s psychological charge lies in that suspended instant before the quill returns to the line.

Costume, Ruff, And The Language Of Status

The sitter’s attire demonstrates rank without ostentation. The voluminous, cartwheel ruff is a masterpiece of paint-handling—tubular petals of linen rendered with crisp highlights and soft interior shadows. It crowns the figure like a halo of craft, a product of ironing, starch, and daily maintenance that speaks to order and propriety. The black leather doublet and sleeves absorb light, their glossy ridges supplying a sober counterpoint to the effusive ruff. A modest ring warms the left hand, its tiny reflection echoing the glow of the page. These details situate the man within a prosperous, disciplined milieu of professionals.

Color And Atmosphere In A Restricted Palette

Rembrandt limits the palette to creams, golds, browns, and inky blacks. This restraint heightens the authority of each hue. The parchment’s buff color carries warmth throughout the scene; the flesh tints of the hands and face live in this same chromatic neighborhood, unifying person and page. Blacks are not monolithic: the doublet’s black is different from the room’s shadow, and the cap’s nap distinguishes itself from the sleeve’s polish. Within this economy, small notes—the rosy interior of the ear, the subtle pink at the fingertips—register with exquisite weight.

Paint Handling And The Material Fiction Of Things

Part of the spell lies in the way paint mimics material. The ruff’s scalloped edges are navigated with a prepared minuteness that never turns brittle; creamy impasto crisps into linen where the light strikes hottest. The book’s leaves receive long, dragged strokes that leave ridges of pigment analogous to paper grain. The table’s covering reads as worn pile, achieved by scumbling thin paint over a darker underlayer so that recession and abrasion appear. Rembrandt calibrates surface for each object, giving the eye tactile cues that the imagination turns into touch.

The Room As Silent Partner

The architecture of the room is barely stated—a wall, a deep niche or cupboard, perhaps the edge of a lectern. This modesty is strategic. Rather than clutter the narrative with learned props, Rembrandt lets darkness bear the weight of context. The scholar’s world is interior and sufficient; the room is a vessel for light and concentration. Subtle horizontals behind the head keep the composition from floating, while the brown-green tonality of the far wall supplies a soft field against which the ruff and face flare.

Identity, Tronie, Or Portrait

Whether this is a named individual or a character study is less important than how the painting performs as a likeness of type: the worker in words. Unlike official portraits that emphasize lineage or office, this picture shows a person defined by what he does. The large book might be a legal register, a theological compendium, or a ledger. Rembrandt avoids specifying to protect the image’s universality. The result is a portrayal that many professions could claim—a preacher checking a sermon, a notary drafting a contract, a scholar annotating a text.

Dialogue With Earlier Works Of Study And Learning

Rembrandt had already explored interior, lamplit scenes in smaller panels and prints of the late 1620s, in which scholars bend over tomes by windows or candles. “A Scholar” distills those experiments. The window as a pictorial device is gone; the light seems inherent, the room a stage for intellect rather than a detailed setting. This substitution of metaphoric light for literal window sets the course for his later masterpieces, where radiance emanates from human action and revelation rather than from external fixtures.

The Hands As Instruments Of Intellect

Few painters render hands with such persuasive individuality. Here they are pale from indoor labor, gently reddened at the joints, the tendons visible where the fingers spread the page. The writing hand holds the quill lightly but decisively, a precision that mirrors mental focus. The ring, placed on the forefinger, catches a speck of light and introduces a circle amidst the scene’s rectangles and arcs. These hands do not merely decorate the portrait; they are the portrait—the thinking body at work.

Narrative Echoes And The Ethics Of Portraying Work

This painting respects labor by representing it truthfully. There is no excessive drama, no theatrical clutter to inflate the scene. The scholar’s world is made of time and tools: book, desk, quill, and light. Rembrandt dignifies the routine of reading and writing, affirming the Republic’s belief that civic life depends on quiet expertise. In doing so he also extends the reach of portraiture to include not only who someone is but how they spend their hours.

The Influence Of Printmaking On Pictorial Focus

Rembrandt’s training as an etcher informs the painting’s clarity. Like an etched plate, the image locates its highest contrasts where the message lies—face and pages—while allowing secondary zones to soften. The way the ruff’s circular rhythms echo the loops of script suggests a printer’s sense for visual rhyme. The subtle reserve of the background resembles plate tone; the crispness of the illuminated edges recalls the bite of acid on copper. This cross-pollination gives the canvas its vivid legibility.

Time, Patience, And The Texture Of Study

The book’s swollen edges and layered bookmarks imply many sessions of reading. Rembrandt captures the temporality of study—the hours required to draw meaning from dense text. Even the slight forward lean of the torso hints at sustained attention. The viewer senses the momentum of a day: notes made, lines traced, the mind periodically surfacing to reflect before diving back into the page. The painting thus becomes a portrait of duration as much as of a person.

Intimacy Achieved Through Scale And Proximity

Although the figure is near life-size, the scene feels intimate because Rembrandt places us within arm’s reach of the book. We are almost at the scholar’s elbow, close enough to hear the scratch of the quill and the rustle of paper. The direct gaze heightens this closeness; we are momentarily the scholar’s interlocutor. This intimacy is not invasive but collegial, as if invited to share in the work for a moment before the writer resumes.

Legacy And The Enduring Image Of the Learned Worker

“A Scholar” helped codify a durable pictorial type: the professional shown at his desk mid-task. Later Dutch painters, and much later artists and photographers, would echo this model when depicting writers, scientists, and clerks. The painting’s authority stems from its balance of honesty and idealization. It exalts the scene not by ornament but by concentration—by granting the ordinary act of writing the stage-space usually reserved for grand narratives.

Seeing The Painting With Fresh Eyes

To appreciate the work fully, one can slow down to the rhythm the scene suggests. Let the eye linger on the variations of black in sleeve and background, the way warm light pools on the wrist, the feathery shadows between the ruff’s folds. Notice how the parchment’s glow subtly illuminates the underside of the chin and the soft center of the ruff, binding page and person. Attend to the tiny highlight at the quill’s tip, the single note that promises the story will continue the moment after this one.

Conclusion

Rembrandt’s “A Scholar” is a compact masterpiece of narrative restraint and optical eloquence. It honors the dignity of learned work with a composition that moves seamlessly between page and face, with light that thinks as it illuminates, and with paint that understands the material character of everything it touches. The sitter’s pause becomes the viewer’s pause, an invitation to consider how knowledge is made: slowly, attentively, by hands and eyes working in concert with the written word. Nearly four centuries later, the quiet glow of that collaboration still compels.