Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

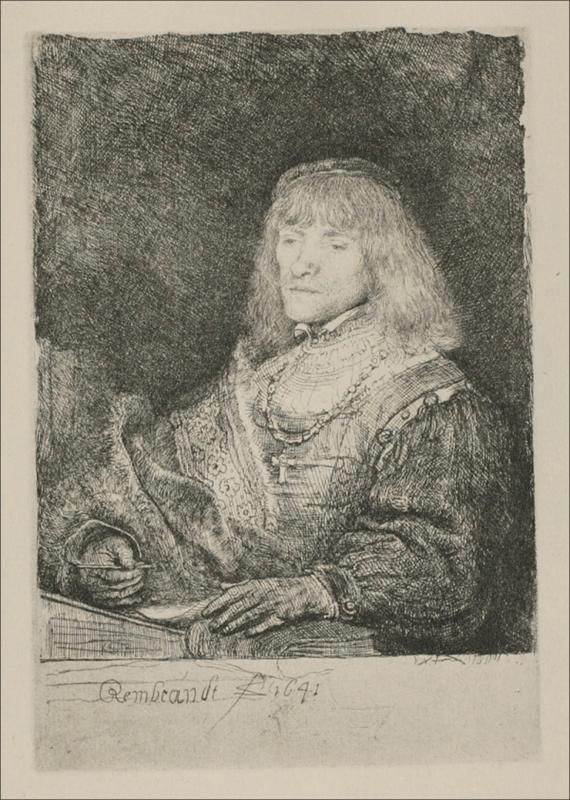

Rembrandt’s “A Man with a Crucifix and Chain” (1641) is a small yet resonant etching that turns a half-length figure into a meditation on faith, status, and the power of line. The sitter—shown three-quarter length, turned gently to the right—wears layered garments embroidered with dense patterns, a soft cap, and, most prominently, multiple chains that culminate in a small crucifix resting at his chest. His right hand holds a writing instrument; his left rests on a book or ledger at the table’s edge. Behind him, a field of richly woven cross-hatching closes like a curtain, pressing the figure forward into the viewer’s space. With a few square inches of copper and an economy of marks, Rembrandt orchestrates material splendor, spiritual sign, and human self-possession into a single, lucid statement.

A Portrait Shaped by the Etching Needle

Although the print has the directness of a portrait, it reads equally as a “tronie,” or character study. Rembrandt exploits the freedom of etching—drawing with a needle through a wax ground so the bite of acid translates thought directly into line—to calibrate the sitter’s presence. Where a painter might build flesh with color, the printmaker varies stroke weight, direction, and density. The face is described with close, carefully modulated hatches that soften toward the cheek and jaw; the garments erupt into a chorus of short, angular marks that catch the glint of embroidery; and the background is woven from deep, overlapping nets of lines that behave like a tonal scrim. The result is at once descriptive and performative: you see a man in ornamented dress, and you also see Rembrandt thinking aloud in copper.

Composition and the Architecture of Presence

The plate’s design pulls the viewer’s eye along a deliberate path. The whitened lower margin—where the artist signs and dates the work—functions as an antechamber; moving upward, you meet the horizontal ledge of the table, then the gloved left hand, then the luminous plane of the book. From there the composition climbs diagonally through the writing hand to the sitter’s chest, where the chains and crucifix form a bright, intricate node. Finally, the gaze arrives at the face, which is slightly set back and modeled with quieter tones, as if character were something steadier and more inward than ornament. The dark field on the upper right balances the mass of figure and costume; it is less background than a counterweight that makes the central light breathe.

The Crucifix and Chain as Luminous Center

The title’s objects are not incidental. Rembrandt stages the jewelry as the visual heart of the print: links rendered with short, incised curves; a cross shaped by the paper’s untouched white and edged with decisive contour lines; and secondary chains that loop and echo like rhythmic afterthoughts. As pure design, these forms knit the torso and head together; as symbol, they announce a life aligned with Christian devotion. The crucifix is small and wearable, not theatrical—an emblem of daily piety folded into the fabric of worldly attire. This dual identity—spiritual sign amid material wealth—summarizes the print’s theme: a person who holds faith and status in balanced tension.

Hands, Book, and the Intelligence of Gesture

Rembrandt often says the most with hands. Here, the right hand lightly grips a pen or stylus, poised as if pausing between thoughts. The left rests on a closed book or ledger, fingers relaxed, gloved for warmth or ceremony. These opposed actions—writing and resting—generate a quiet narrative: a cultivated person midway through reading, noting, or signing a document. The gestures never overact. The knuckles bulge as they must; the fingertips press gently into leather; the wrist bends with believable weight. Because the gestures are true, they extend the sitter’s psychology: reflective, practiced, and at ease with instruments of literacy.

Costume as a Workshop for Line

The garment is a concert of etched techniques. Parallel hatches describe the cloth’s weight; stippling and short diagonals stand in for stitched ornament; and clustered lines swelling and thinning with pressure suggest the irregular sheen of brocade. Rembrandt enlarges and simplifies motifs just enough for them to read in print, while keeping them irregular so they feel made rather than printed wallpaper. The garment’s dark mass also frames the face and jewelry, acting as a tonal reservoir that lets bright accents spark. Texture becomes more than depiction: it is the engine that distributes force across the plate.

The Face as a Weather Map of Light

The head tilts slightly upward, eyes almost closed, as if the sitter were tasting thought or catching distant sound. Rembrandt spares the face extraneous detail, allowing the lightest paper to glint at the forehead and nose while shading the cheeks with shallow, parallel strokes. Where the skin thins—along the eyelids and at the philtrum—his line slows into delicate calibrations. The restraint keeps the face from competing with the jewelry and hands, and it emphasizes temperament over likeness. We read quiet self-assurance, a certain inwardness, and the calm of someone who inhabits both faith and responsibility.

Chiaroscuro and Plate Tone

The atmosphere owes much to the way the plate was wiped before printing. Rembrandt often left a film of ink—plate tone—on the copper so that areas of the print carry a soft veil, especially in the upper field. Here the heavy tone at the top and right drops like a stage drape. The cleaner wiping around the head and chest opens a cone of light that reads as window-glow or lamplight. This manipulation is not an afterthought; it is part of composition. Tone establishes where the eye lingers and how the space breathes, giving the figure the aura of a person standing just inside the threshold of a dim room.

Faith, Status, and Seventeenth-Century Context

In the Dutch Republic, jewelry and chains often signaled office or achievement, while the crucifix, though identifying a Catholic devotion, could also be worn by anyone who valued the cross as a personal emblem. Rembrandt is less interested in strict denominational labeling than in the visible coordination of belief and public life. The sitter’s literate tools—book and pen—situate him among the Republic’s culture of reading; the chain claims worldly station; the crucifix insists that the heart has its anchor. Without overt moralizing, the print posits an ethic familiar to Rembrandt’s portraits: virtue arises where interior conviction and exterior duty meet.

The Poetics of Restraint

Despite the dense cross-hatching and ornamental dress, the print feels remarkably calm. Rembrandt achieves this through restraint in crucial places: he leaves the book’s pages lightly described; he refuses to over-model the hands; he suppresses background detail; and he keeps the face open and breathable. The bright crucifix, precisely because it is small and simply drawn, becomes the picture’s still point. Everything else, however richly rendered, revolves around that modest form.

Relation to Rembrandt’s Tronies and Portraits

This sheet stands midway between Rembrandt’s anonymous character studies and his commissioned likenesses. Like a tronie, it explores a type—a reflective, well-dressed man of means and conscience—without tying itself to a name. Like a portrait, it grants individual gravity and the subtleties of personal habit: the fall of hair, the slight tilt of head, the specific way a glove wrinkles. This dual allegiance allowed Rembrandt to circulate such prints widely. Collectors prized them for their combination of human insight and technical bravura; artists studied them as portable lessons in light, texture, and stance.

The Rhythm of Lines and the Music of the Plate

One can almost hear the plate’s music. In the background, cross-hatches hum like sustained chords. In the garment, shorter, syncopated marks suggest ornamented rhythms. In the jewelry, bright, isolated strokes ring like small bells. The face and hands occupy a quieter register, where lines breathe and rest. This musical structure guides the viewer through the image with a sense of phrasing: introduction at the table, crescendo at the chains, calm resolution at the face.

The Viewer’s Experience and the Ethics of Looking

Rembrandt places us at conversational distance across the table, close enough to inspect the crucifix and the minute structure of links, but far enough to prevent voyeurism. The sitter’s almost-closed eyes deny the theatricality of a returned gaze, keeping the encounter contemplative. We observe without being tested. The print enacts a respectful etiquette: look carefully, acknowledge the symbols others carry, and allow them the dignity of thought.

Modernity in an Early Modern Print

To contemporary eyes, the image feels unexpectedly modern. The shallow space, the dark field, the concentrated lighting, and the absence of props beyond book and pen anticipate the language of studio portrait photography. The symbolic economy—a single cross as the entire argument—reads with minimalist clarity. And the visibility of process—the etched line’s speed, pressure, and hesitations—aligns with today’s appreciation of craft transparency. The print remains fresh because it trusts essentials.

Lessons for Image-Makers

From this etching, painters, designers, and photographers can draw practical lessons. Use asymmetry to stabilize a square or vertical format. Deploy a bright focal node—here, the crucifix and chain—against a darker field to concentrate attention. Vary line or texture to differentiate materials. Let faces breathe; leave some surfaces undertold so others can sing. Above all, integrate symbol with gesture: the cross matters more because the hand that writes and the book that waits share the frame.

On States, Impressions, and the Life of the Plate

Rembrandt’s plates often passed through multiple states, as he deepened lines or adjusted passages. Even within a single state, differences in inking, wiping, and paper produce diverse atmospheres—some impressions will feel duskier, others brighter. That variability is not noise; it is part of the work’s identity. Like a sitter whose expression shifts subtly over a sitting, the print has many moods, each true to the plate.

The Quiet Drama of Belief

No narrative incident occurs: no vision, no exchange, no miracle. Yet a quiet drama unfolds. A man who writes and reads wears a cross. The light that glances off silver also finds his face. A heavy garment that could have been ostentatious becomes supporting architecture for a small sign of love and suffering. Rembrandt’s serious mercy—his habit of granting even ornament the dignity of restraint—lets the viewer contemplate how convictions lodge in daily life.

Conclusion

“A Man with a Crucifix and Chain” is the kind of Rembrandt print that grows larger the longer one looks. In a small field of copper, he aligns craft and insight: etching’s virtuosic line, plate tone’s breath, the choreography of hands, the orchestra of textures, and a single emblem that holds the picture’s meaning. The sitter emerges as literate, measured, and devout—an individual in whom worldly capacity and inner fidelity rhyme. Four centuries later, the print still reads with clarity because it trusts the simplest argument a portrait can make: show a person’s tools, show their signs, let light touch the face, and the viewer will understand.