Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to A Girl and her Duenna

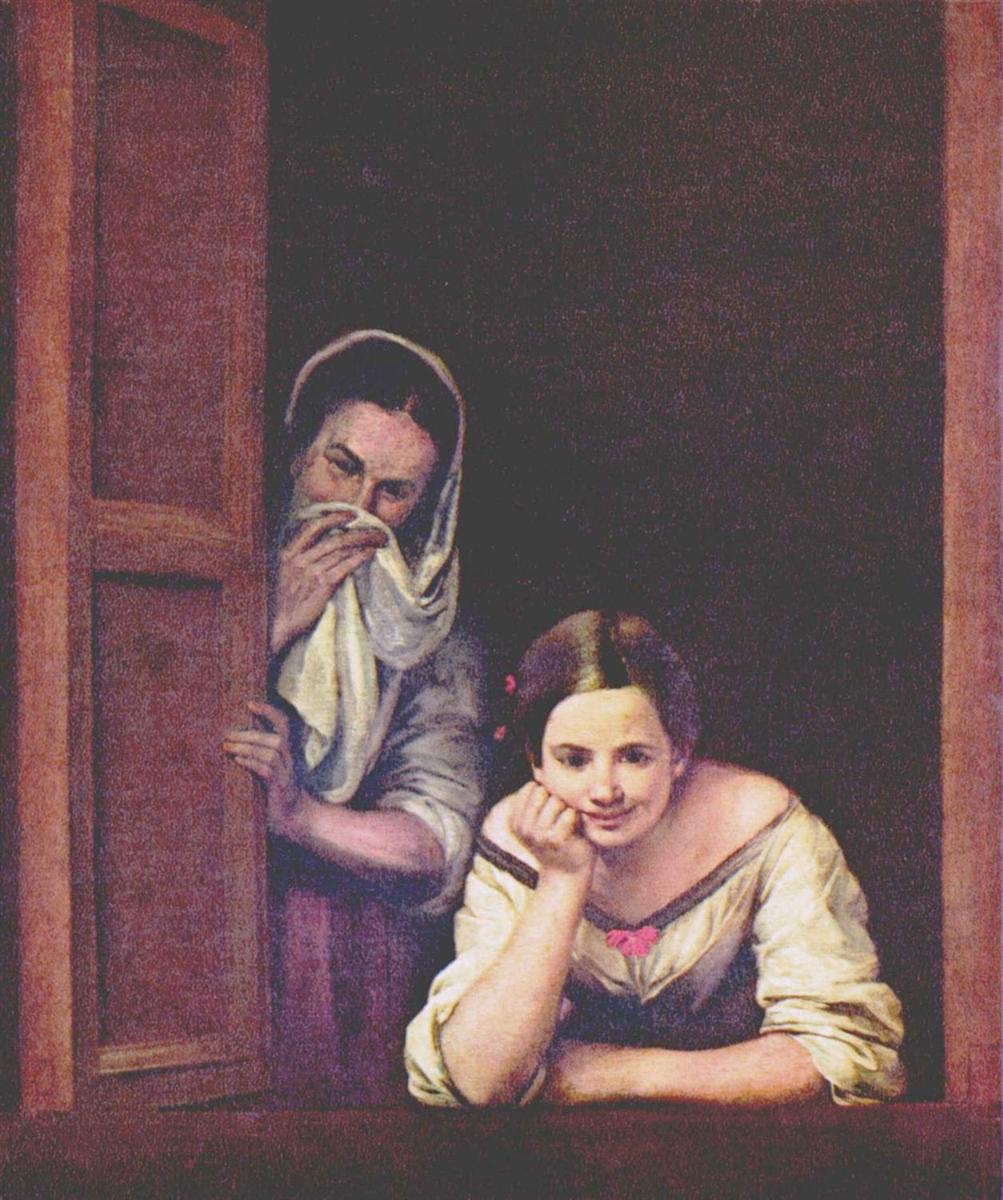

“A Girl and her Duenna,” painted by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo around 1670, is one of the artist’s most fascinating genre scenes. At first glance the painting seems simple. A young woman leans over a window ledge with an engaging smile, while an older woman, her duenna or chaperone, hovers behind, partly concealed by the shutter and a white cloth. Yet this apparently casual scene at a window captures a complex web of social codes, gender expectations, and emotional contrasts in seventeenth century Seville.

Murillo was renowned for religious works that glow with spiritual tenderness, but he also excelled in scenes of everyday life. In “A Girl and her Duenna” he turns his observational skill to the world of Spanish households, where young women were carefully guarded and courtship unfolded under the watchful eyes of older relatives. The painting hovers between humor and seriousness, charm and caution, offering a subtle commentary on the boundaries between innocence and experience.

Composition and Framing at the Window

The entire scene is framed by a window opening, which functions as both literal and symbolic border. Murillo places the viewer outside the building as if we are walking along a street and glance up to find these two figures looking down. The girl leans on the bottom ledge with her elbows, projecting into our space, while the duenna stays further back within the dark interior.

This use of the window frame turns the painting into a stage. The vertical posts and the shutter create a strong architectural structure that anchors the composition. The figures occupy the lower half of the canvas, leaving a large area of deep shadow above them. This choice focuses attention on their faces and gestures. The darkness behind them emphasizes the sense that we are seeing something private that has been momentarily revealed.

Murillo balances the composition carefully. The older woman occupies the left side, her cloth and veil echoing the vertical shutter. The girl dominates the right side, where her pale blouse and bare arms form a powerful light shape against the dark background. The diagonal of her forearm, resting on the sill, leads directly to her face, which becomes the visual and emotional center of the work.

Light, Shadow, and the Baroque Sense of Drama

Light enters the scene as if from the street, striking the girl full on and illuminating part of the duenna’s face and hands. The strong contrast between light and shadow reveals Murillo’s understanding of Baroque chiaroscuro, a technique he absorbed from the broader European painting of his time.

The girl’s skin is warm and luminous. Her blouse glows with a soft, creamy tone that gently transitions into shadow around the folds of fabric. The older woman, by contrast, remains half hidden. The light catches only the upper part of her face, her knuckles, and the crisp white of the cloth she holds to her mouth. The darkness around her suggests interiority and secrecy.

This play of light and shadow does more than create three dimensional forms. It reinforces the psychological contrast between the two figures. The girl belongs to the world of light, youth, and open curiosity. The duenna occupies a more ambiguous middle ground between watching and hiding, vigilance and complicity. Murillo presents their relationship through light itself.

The Expressive Young Girl

The young girl in “A Girl and her Duenna” is one of Murillo’s most charming secular figures. Her pose is relaxed and natural. She leans forward on her left elbow, her chin resting on her hand, while her right arm drapes casually along the sill. Her shoulders tilt slightly, and the neckline of her blouse slips low enough to reveal the grace of her collarbones without crossing into impropriety.

Her expression is a mixture of amusement and self awareness. She smiles softly, lips closed, as if enjoying a private joke or responding to someone just outside the frame. Her eyes are bright and directed outward, engaging the viewer or an imagined passerby. There is nothing stiff or idealized about her face. She appears as a real Sevillian girl, lively and intelligent, fully aware that she is being observed.

Murillo pays close attention to details that underline her youth. Her hair is parted in the center, smoothed back, and tied with small pink ribbons that echo the tiny colored bow at the neckline of her blouse. The rolled up sleeves reveal strong forearms, suggesting that she is not an aristocratic lady but a young woman of the urban middle or artisan class. Her weight resting comfortably on the sill suggests confidence, perhaps even a hint of flirtatious boldness.

The Watchful Duenna

Behind her stands the duenna, traditionally an older woman appointed to chaperone respectable girls and protect their reputation. Murillo paints her in a very different key. She is wrapped in a veil and scarf, fully covered, with only her face and hands visible. She clutches a white cloth to her mouth, a gesture that can signify modesty, secrecy, or perhaps the attempt to conceal a smile.

Her gaze is not directed at the girl but out toward the street, in the same general direction as the younger woman’s. Yet her expression is more wary. Murillo draws her eyebrows together slightly, and the shadows under her brow deepen the look of concern. She seems torn between disapproval and indulgence. On one hand, her duty is to guard the girl from unwanted advances. On the other, she may feel nostalgia for her own youth and the excitement of courtship.

The duenna’s presence introduces tension into the painting. Without her, the scene would simply be an appealing portrait of a girl at a window. With her, the viewer becomes aware of the constraints of social decorum. The older woman is both a guardian and a witness, ensuring that whatever interchange takes place between the girl and the outside world remains within the boundaries of propriety.

Social Context and the Spanish Idea of Honor

To understand the dynamics between the girl and her duenna, it is helpful to remember the importance of honor in seventeenth century Spain. A family’s reputation depended heavily on the visible virtue of its women, especially young unmarried daughters. Public flirtation or unsupervised conversation with men could damage that reputation.

A duenna was therefore not simply a servant but a guardian of honor. Her role was to accompany young women in public, monitor interactions, and report any questionable behavior. At the same time, in plays and literature of the period, duennas are often portrayed with humor. They sometimes aid in secret romances or become unwitting participants in the young people’s schemes.

Murillo captures this cultural nuance beautifully. The older woman’s protective posture and partially hidden face signal her official role as chaperone, yet the soft humor of the scene suggests she might be more lenient than her stern appearance implies. The painting seems to hover on the boundary between vigilance and collusion in youthful amusement.

Intimacy, Humor, and Possible Narratives

One of the pleasures of “A Girl and her Duenna” lies in how much narrative it suggests with so few elements. We see only two women at a window, but the implied story extends beyond the frame. Perhaps the girl is leaning out to watch the street, where soldiers, students, or merchants pass by. Maybe she has noticed a particular admirer and waits for him to look up. The slight tilt of her head and knowing smile suggest a specific object of attention.

The duenna, meanwhile, might be pretending to reprimand or counsel her while secretly enjoying the scene herself. The cloth over her mouth may hide a chuckle as much as a frown. Murillo leaves these possibilities open, allowing viewers to invent their own scenarios.

There is gentle humor in the contrast between the girl’s fresh face and the duenna’s cautious posture. Yet the humor never becomes cruel. The older woman is not caricatured but treated respectfully, with her own dignity and complexity. The relationship between the two appears affectionate, not adversarial. The painting portrays a moment of everyday domestic theater in which both women participate.

Color, Texture, and Painterly Detail

Murillo’s color palette in this work is restrained yet effective. The warm reddish tones of the wooden frame harmonize with the earthy browns of the girl’s skirt and the subdued mauves in the duenna’s clothing. Against this subdued range, the creamy white of the young woman’s blouse and the bright highlights on her skin stand out strongly.

The older woman’s veil is painted with gentle grayish whites that blend into the surrounding shadow, implying softness and age. The cloth she holds is rendered with crisp edges and small folds, catching touches of light that draw attention to her gesture. Murillo’s brushwork is subtle. He uses smoother strokes for the faces and hands, preserving clear form and expression, while allowing slightly rougher handling in the fabrics and wood.

The background is an almost uniform dark brown, with only slight variations in tone. This flat darkness pushes the figures forward and simplifies the composition. We are not distracted by interior details or street scenery. All the painterly energy is focused on the two women and the psychological space between them.

Genre Painting and Murillo’s Reputation

“A Girl and her Duenna” belongs to Murillo’s small but significant group of secular genre paintings. While he is best known for religious scenes such as the Immaculate Conception, the Holy Family, and images of saints, he also painted street children, beggars, and domestic interiors. These works reveal his deep interest in the everyday life of Seville.

In this painting, Murillo applies the same sensitivity he brings to his sacred subjects. He treats the young girl with the tenderness usually reserved for images of the Virgin or child angels. Her humanity is depicted with warmth and respect, not as a mere object of male gaze but as an individual with feeling and a subtle sense of humor.

At the same time, the painting shows Murillo’s awareness of different audiences. A work like this likely appealed to urban patrons who enjoyed clever, lifelike scenes that reflected their own world. The painting invites viewers from the seventeenth century to recognize familiar social roles and perhaps to smile at the antics of youth under supervision. For modern viewers, it offers a valuable glimpse into the gender customs of Golden Age Spain while still feeling surprisingly fresh and relatable.

Psychological Depth and the Viewer’s Role

One of Murillo’s great achievements in “A Girl and her Duenna” is the psychological depth achieved without elaborate narrative devices. The interaction of glances and gestures is enough to create a layered experience. The girl’s eyes and smile pull the viewer into a direct relationship. We become the one at whom she smiles, the passerby who has unwittingly become part of her game.

The duenna’s sideways glance, less direct yet still outward, complicates this relationship. We feel scrutinized. It is as if the painting asks us to consider our own role as observers. Are we innocent onlookers, or are we participating in a flirtation that tests social limits? Murillo involves the viewer, making the act of looking itself part of the subject.

This subtle self awareness aligns the painting with broader Baroque concerns about appearance, reality, and theater. The window frame resembles a proscenium arch, and the figures perform a small drama for anyone who passes. Yet, unlike in a formal theater, the boundaries between actors and audience remain porous. We are not just watching the scene we are implicated in it.

Legacy and Continuing Appeal

Today “A Girl and her Duenna” is admired for its psychological nuance, its masterful handling of light, and its charming portrayal of feminine youth and age in dialogue. The painting has become one of the most frequently reproduced of Murillo’s genre works because it condenses so much humanity into a simple composition.

For art historians, it provides evidence of how Golden Age Spanish artists used genre painting to explore social themes such as honor, gender roles, and domestic life. For general viewers, it offers an immediately relatable moment. The shy watcher and the confident young woman at the window feel timeless. Many people can find echoes of their own experiences of being supervised as teenagers or of looking out with curiosity at the wider world.

Murillo’s ability to communicate across centuries arises from his combination of technical skill and empathy. He paints not only what people look like but what they feel. “A Girl and her Duenna” remains a vivid example of how a quiet household moment can reveal the complexities of an entire culture.