Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

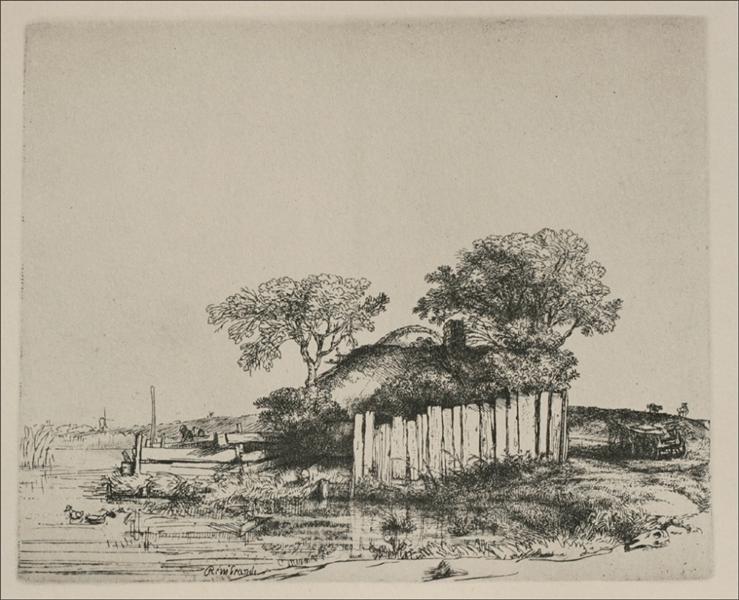

Rembrandt’s “A Cottage with White Pales” (1642) is a small etching that opens into a surprisingly generous landscape. At first glance, the scene seems almost offhand: a simple dwelling tucked behind a paling fence, trees massed above a thatched roof, a shallow canal in the foreground with reeds and a skiff, and distant structures dissolving into soft air. Yet within that modest arrangement Rembrandt compresses a world of observation—how wind lays itself along grasses, how boards weather and warp, how water receives and returns the things set beside it. With nothing more than copper, acid, ink, and paper, he creates a sweep of open sky and an atmosphere that feels Dutch to the bone: practical, windswept, and lucid. The print belongs to the artist’s great decade of landscape etchings, in which he roamed the outskirts of Amsterdam and translated the ordinary edges of the city into images of attention and rest.

Subject and Setting

The title identifies the focal structure: a cottage fenced with bright pales. The house has a low, rounded thatch; trees press in close, their foliage cushioning the roofline as if the dwelling were grown rather than built. At the right, the paling forms a semi-circular enclosure with irregular verticals, some posts leaning or split, others newly set. A small chimney peeks from the thatch, a quiet proof of habitation. The left foreground holds water crossed by a simple landing. A skiff with figures suggests slow travel or work; a few ducks ripple the surface near a stand of reeds. In the far distance, a faint windmill rises against the horizon, indexing the Netherlands’ familiar marriage of engineering and sky.

Composition and the Balance of Masses

Rembrandt’s composition is beautifully asymmetrical. He clusters the main weight—cottage, trees, fence—on the right half of the sheet, leaving the left to water, reeds, and far-off forms. This imbalance creates movement from right to left, a gentle pull that begins in the dark huddle of vegetation and drifts across the canal toward the distant town. The curve of the paling is crucial. It echoes the mound of the thatch and anchors the composition with a firm semicircle, like an architectural comma in a long sentence of horizon. Meanwhile, the low shoreline and the skiff on the left counterbalance the dense mass of foliage, keeping the image from toppling. Rembrandt also uses the tall trunks to punctuate the skyline; their canopies expand like clouds, softening the verticals of the fence below.

Light, Air, and Tonal Architecture

The print’s light is built as much by restraint as by marks. The open sky is left almost entirely blank, a field of paper that reads as northern air. Against that pale the dark mound of the cottage grows luminous—light described by the neighborly presence of shadow rather than by drawn rays. The “white” pales, despite being drawn in ink, read as bright because Rembrandt encloses them with darker grasses and the shadowed base of the hedge. The canal is a mirror that holds the world lightly; thin, horizontal hatchings suggest a changing surface, and a few darker strokes indicate reflections of fence and foliage without insisting on exact symmetry. Tonally, the sheet is a pyramid: darkest at the foot of the cottage and in the hedge, medium in the water and distant bank, and lightest in the sky.

The Etcher’s Line and Touch

Rembrandt’s line here is quick and conversational. He varies pressure and spacing to summon different textures: feathery loops for leaves, straight irregulars for pales, compact mesh for the hedge’s core shadow, long gliding strokes for water. The thatch is indicated with short, slightly curved dashes that run with the roof’s contour, giving the sense of layered reeds. In the grasses he allows lines to escape like stray blades, an improvisational flourish that keeps the ground lively. The fence posts are not ruler-straight; tiny wobbles and breaks record weathering and hand-made construction. Everywhere the line shows both knowledge and affection, the warmth of someone drawing what he has walked past more than once.

The Motif of the White Pales

The paling is more than a practical fence; it is the image’s emblem and its title. Rembrandt uses it to think about enclosure and exposure. The posts protect a modest domestic sphere—garden, animals, tools—while also declaring it to the world. The pales are “white” because the eye, bathed in the blank sky, assigns brightness to anything standing clear against darker vegetation and reflected in water. Their rhythm, with irregular intervals and heights, keeps the sheet from becoming static; they beat time like a soft percussion through the right foreground. Their reflection in the canal doubles their presence and ties house to water, land to the broader routes of trade and travel.

Water, Reflection, and Quiet Movement

The canal is the print’s breath. It receives reflections from the fence and foliage, but Rembrandt does not pursue mirrorlike accuracy. Instead, he allows the water to tremble, broken by ripples, reeds, and the slow approach of a skiff. A single vertical pole near the landing gives the left side a counterpoint to the fence’s up-standings. The ducks set a domestic scale; they also puncture any temptation to solemnity. Water in Rembrandt’s landscapes often serves as a slow-moving stage on which everyday life glides. Here, its horizontal calm balances the upward push of trees and pales, making the scene feel settled.

Human Presence and the Measure of Scale

Figures are small: a boatman or two near the landing, perhaps a person by the fence, barely more than a few notches of the needle. Their minuteness matters. It assigns true scale to the trees and the house and keeps the print intimate rather than theatrical. The cottage reads as lived-in not because we see its inhabitants clearly but because everything in the drawing speaks of daily use—worn paths, mended pales, a tended hedge, the boat’s habitual route. The human presence is everywhere encoded in maintenance.

Space, Distance, and the Long Horizon

Rembrandt achieves distance with astonishing economy. A few thin horizontals and light verticals conjure far fields. The faint silhouette of a windmill or church tower at the left horizon signals miles without needing detail. The sky remains unmarked, a gulf of pale that draws the eye outward and upward. Against that emptiness, the cottage’s mound and its close company of trees feel especially snug. The image therefore offers two pleasures at once: the protected near-at-hand and the expansive far-away.

Weather, Season, and the Sense of Time

The print registers a fair-weather day with dry air and good visibility. Leaves are full; grasses are plentiful; the thatch looks sound. But Rembrandt always allows time to touch his motifs. The paling’s varied condition, the slight subsidence of ground around the posts, and the hedge’s dense heart suggest seasons of growth and mending. This is not a brand-new farm but a place that has yielded to wind and work. The canal’s level is low enough to expose clumps of bank vegetation—an index of tides and sluices that rule Dutch waterland. The whole scene breathes the slow tempos of rural maintenance.

Landscape as Character

Rather than treating the cottage simply as architecture, Rembrandt characterizes it. The round, almost burrow-like thatch and the pressing trees give it the feeling of a creature nestled into a bank. The fence stands like ribs; the chimney is a small, alert ear. This quiet anthropomorphism is never cute; it is a byproduct of empathy. The artist’s line humanizes what it touches. In doing so, he grants the place dignity: a poor dwelling perhaps, but not mean; a dwelling woven into its environment and therefore strong.

Comparisons within Rembrandt’s Landscapes

Compared to his dramatic etched views with storm skies, bridges, or towering trees, “A Cottage with White Pales” is a study in restraint. It lacks theatrical chiaroscuro, choosing instead clarity and balance. Yet it shares with those works the hallmark of Rembrandt’s landscape art: the sense that the world has been looked at in weather, on foot, with affection. In prints such as his views along the Amstel or the “Cottage with Dutch Canal and Swans,” he marshals similar devices—blank sky, reflective water, a huddle of structures—to create space that exceeds the sheet. The present print is among the most intimate and lyric of the group.

The Print as Object: Plate, Ink, and Paper

As with many of Rembrandt’s etchings, impressions vary. Crisp early pulls display needle-fine grasses and delicate hatchings in the sky’s lower band; later, as the plate wears, the lines soften and the whole scene grows slightly hazier, which can read as afternoon warmth. Paper choice matters enormously: a warm, slightly toned sheet deepens the mid-tones and turns the “white” pales into gentler ivory; a whiter paper emphasizes the contrast and makes the sky more brilliant. The artist’s signature, lightly tucked in the foreground near the bank, anchors the sheet not as a boast but as a personal witness to the view.

The Dutch Republic and the Meaning of the Cottage

In the seventeenth-century Netherlands, the humble cottage was an emblem of national self-understanding. Prosperity bloomed in cities, but it rested on reclaimed land, disciplined water, and the steady labor of households like this one. Rembrandt’s image honors that economy without propaganda. The paling speaks of property and care; the skiff hints at commerce and connection; the windmill at the horizon stands for the country’s engineered housekeeping. At the same time, the generous sky and clean air declare that such labor unfolds within a creation roomy enough for wonder.

Psychological and Poetic Readings

Viewers have long sensed in this print a promise of refuge. The fencing, while defensive, is thin and permeable; the house is embraced by trees rather than barricaded by walls. The open left side and the canal lead the gaze to a wider world, suggesting that safety and openness are not opposites. The image becomes a meditation on sufficiency: a place just large enough, a fence just strong enough, a sky just empty enough to make breathing easy. It is also a picture of listening. The clustered trees lean inward as if to hear the slight noises of household life within.

Looking Notes for Painters and Photographers

For artists studying structure, the print is a primer in massing and value. Rembrandt groups his darks—hedge, lower foliage, fence shadows—so that the eye reads a single coherent shape before it subdivides. He lets the middle tones live in the water and distant bank, then reserves his lightest area for the sky and pale-white fence. For photographers, the lesson is similar: anchor the frame with one major mass, offset it with a counter-mass, and keep sufficient negative space to let the subject breathe. The result is calm without dullness.

Legacy and Influence

Rembrandt’s landscape etchings influenced generations of printmakers who learned from his fearless use of blank paper as light and his avoidance of prettiness. Painters of the Dutch countryside and, much later, artists of the Barbizon and Hague Schools admired his ability to make low subjects—cottage, ditch, hedge—carry poetic weight. The print’s emphasis on lived texture rather than picturesque arrangement anticipates a modern sensibility that finds beauty in usefulness.

Conclusion

“A Cottage with White Pales” is a hymn to modest order. It turns fence posts, thatch, and canal into a balanced chord of form and feeling. The scene is specific—one fence, one roofline, one bank of reeds—and yet it seems to stand for many such places along the Dutch waterways. Rembrandt, at the height of his powers, can conjure such fullness with a minimum of means: a few dozen kinds of line, carefully judged spaces of untouched paper, a composition that trusts the eye to travel and the mind to rest. In this cottage behind its paling we glimpse an ideal of habitation—secure, permeable, cultivated, and at peace with its long horizon.