Image source: wikiart.org

First Encounter With A Ragged Silhouette And A Human Aside

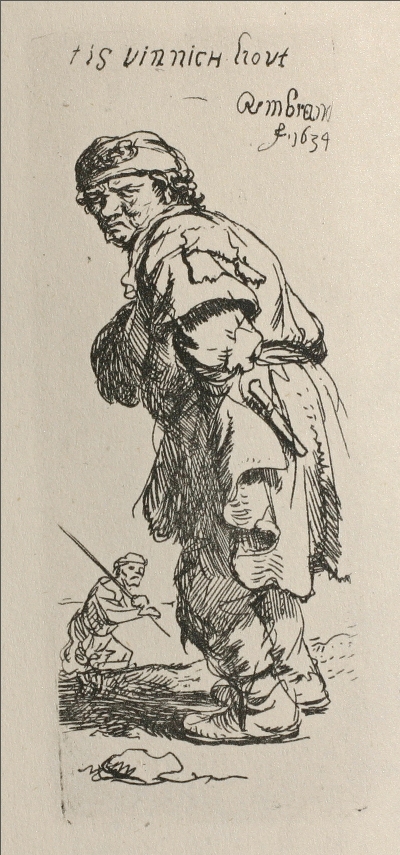

Rembrandt’s “A Beggar and a Companion Piece, Turned to the Left” (1634) looks disarmingly simple at first glance: a tall, bundled figure trudges across the page while a smaller companion crouches behind him with a stick. But the longer you look, the more the drawing opens—into a study of movement, humor, social vision, and the quicksilver precision of line. Above the figures, Rembrandt has written a short phrase in his own hand, the kind of marginal note that makes the sheet feel overheard rather than staged. The inscription, brisk and colloquial, folds weather and voice into the image. What we meet is not a symbol but two people caught between steps on a cold day, recorded by an artist acutely awake to dignity even at the edge of society.

A Composition Built On Unequal Scales And Walking Time

The drawing relies on a witty misalignment of scale. The main figure, turned to the left, fills most of the vertical. Heavy layers—cap, cloak, patched tunic—stack into a silhouette that reads instantly even at a distance. The smaller companion crouches lower right, head down, one hand gripping a stick set diagonally into the ground. The two bodies are bound by a narrow path of hatching that indicates earth and by a barely suggested landscape that keeps them from floating. The page’s empty space is purposeful; it becomes cold air. Read from top to bottom, the drawing behaves like walking itself: a stride begun, a pause behind, a destination outside the paper’s edge.

Line As Voice: Drypoint Clarity With A Calligrapher’s Ease

The sheet is a master class in how a few kinds of stroke can carry the heft of a life. Short, parallel hatches knit the bundle of the cloak; broken contour lines let the eye finish the ragged hem; tight curls build hair and cap; quick zigzags turn dirt into ground. Nothing is labored. Rembrandt’s line declares, suggests, and leaves off at exactly the moment your perception can take over. The effect is a drawing that feels spoken rather than carved—a voice that trusts the listener. Even small textures, like the ribbed stocking or the patched elbow, arrive as a handful of marks that are more readable than fussy detail would be.

The Inscription That Turns Weather Into Story

At the top, Rembrandt writes an offhand sentence in Dutch (commonly read as “’t is vinnich kout,” meaning “it’s bitterly cold”), followed by his signature and date. This scribble is not decoration; it is dramaturgy. It supplies temperature, tone, and time. The big figure’s hunched shoulders and tucked head suddenly acquire motive; the little companion’s grip on the stick becomes a practical brace against a frozen path. With eight or nine inked words the drawing converts from generic “beggars” into a specific, shivering morning in the 1630s. The text also collapses distance between artist and subject: we hear the weather as the artist did, and we see as he speaks.

Gesture And Clothing As a Grammar Of Survival

Every fold is functional. The big figure wraps the cloak not with theatrical flourish but with the tight economy of someone who counts heat. The cap fits low; the tunic falls in layers that thicken where wind would bite. The companion’s crouch is less a pose than a tactic—lower center of gravity, stick as third leg, head under the line of weather. Rembrandt is careful to avoid caricature. Feet are big because boots are thick; hands are hidden because mitts and sleeves exist; posture is stooped because a life of carrying and cold makes a back honest. The drawing respects the work that is survival.

Humor Without Cruelty

There is wit here, but never mockery. The large figure’s profile mutters a little, as if he is speaking the very phrase the artist inscribes. The small figure’s exaggerated crouch and stick could tip toward cartoon in lesser hands. Rembrandt keeps them human by calibrating proportion and weight. The big man’s mass rests convincingly on his leading foot; the little companion’s stick digs into the ground with a believable angle; the shadows under soles are just dark enough to carry heft. We smile with them, not at them, because their world makes physical sense.

The Ethics Of Looking From The Side

The turn to the left is a compositional choice that doubles as ethics. Rembrandt does not confront the beggar head-on, nor does he hide behind distance. He walks beside him—slightly behind, slightly to the side—attending to motion more than to face. That side-on nearness places the viewer in a respectful relation: close enough to note detail, not so close as to invade. It is a way of seeing that the artist uses repeatedly in his studies of workers, beggars, and street figures. The side-view honors someone’s trajectory rather than arresting it for inspection.

Paper As Weather And Silence

The wide, empty field of the sheet matters. Against it, the ink reads like breath condensed in cold air. The absence of background tricks is not laziness; it is a decision to make the white of the paper act like the space the figures occupy. The small hummock near the bottom, sketched with a few flicks, keeps the ground believable without clutter; a faint horizon may be suggested by the sweeps around the companion’s head. Rembrandt knows when to stop. In a drawing about cold, leaving space cold is part of the truth.

Patches, Seams, And The Touch Of Poverty

Rembrandt’s sympathy lives in his attention to edges. The sleeve patch is a sliver darker than the cloth around it; the tunic’s torn hem is clarified by a jag of line; the stocking’s wrinkles are vertical, because gravity is. Poverty becomes legible through sewing and wearing rather than through editorial labels. The artist resists the moralizing tendency of emblem books in which beggars symbolize vices. His beggar symbolizes himself: a person with a body, moving through weather, using what is available to get where he must go.

The Companion As Chorus

Why the small companion? In part, to supply rhythm and scale; in part, to turn a portrait into a scene. The crouching figure makes the big man bigger, but he also activates the space between figures, pulling an invisible tether—friendship, need, work—across the page. The diagonal of the stick ties ground to body, adds a counterslant to the big figure’s forward tilt, and gives the group a shared task: getting through. In theater terms, the companion is chorus, echoing and grounding the main action without stealing it.

Speed And Certainty In The Making

If you follow the line, you can reconstruct the order of the drawing. The contour of the large figure likely came first, a single sweep for cap, back, and cloak; then the inner folds and sleeve; then the shoes and ground to lock him in place. The companion arrives afterward, his tiny head and stick added to balance the page. The inscription caps the scene like a spoken title, and the signature takes ownership of the moment. The speed is part of the sheet’s charm: it feels like a glimpse captured while walking—just enough time to draw, no time to fuss.

A 1634 Lens On Amsterdam’s Social Fabric

The year 1634 places the sheet in Rembrandt’s early Amsterdam period, when the city swelled with sailors, craftsmen, refugees, and the poor who serviced an expanding economy. Artists frequented markets and alleys for subjects, and prints of beggars by Jacques Callot and others circulated widely. Rembrandt absorbs the genre but resists its cruelty and ornamental poverty. Instead of turning the beggar into a decorative grotesque, he makes him a neighbor. The phrase about cold acknowledges shared weather. The drawing’s ethics are therefore civic as much as artistic.

Compared To Painted Grandeur, A Different Kind Of Power

In the same years, Rembrandt painted gilded chains, lace, and velvets in commissioned portraits. This sheet runs the other way—ink, rags, street. The connection is not contradiction but extension. The same eye that measures light on satin measures darkness on a patched sleeve; the same compassion that ennobles a merchant’s face preserves the humanity of a man without coin. Both worlds are Amsterdam. Rembrandt’s greatness lies partly in refusing to separate them inside his attention.

The Phrase As Soundtrack And Temperature Gauge

Because the words are present, the drawing almost has sound. We hear a grumble, feel the wind, and taste the sting of air. The phrase does not patronize; it testifies. It also reveals something about Rembrandt’s working method: he did not merely copy bodies; he listened. The scribble converts the page into a piece of fieldwork. Modern viewers, accustomed to snapshots with captions, will recognize the freshness of that practice.

Movement, Balance, And The Micropoetry Of Feet

Take a last look at the shoes. The big figure’s leading foot plants heel first, toes slightly lifted; the trailing foot is still flexed, the boot’s sole indicated by a flattened dark shape. These two simple forms—no more than ovals with a couple of cuts—contain gait, weight, and direction. The companion’s feet point outward for stability. A small dark under each shoe is enough to bind them to the earth. This is Rembrandt’s micropoetry: small marks doing big work.

The Drawing As A Portable Moral

The sheet does not preach, yet it offers a moral that travels easily: attention confers dignity. By taking the time to record these two figures with economy and tact, the artist argues that no life is beneath the grammar of art. Viewers carry that argument away from the drawing into their own streets. The afterimage is not of “types” but of people you might step aside for, or greet, or see.

How The Image Still Feels Contemporary

The drawing’s modernity lies in its refusal of melodrama and its affection for the ordinary. It could be a sketch in a contemporary artist’s notebook: two figures hunched against wind, a line of text like a social-media caption, the world pared to essentials. The ethics of looking from the side, the humor without cruelty, and the tact of leaving space blank remain powerful in a culture saturated with images that either exploit or ignore the poor. Rembrandt’s sheet models a third way: meet, record, respect.

Closing Reflection On Ink, Weather, And Fellowship

“A Beggar and a Companion Piece, Turned to the Left” compresses fellowship into a handful of lines. A cold sentence at the top turns ink into air; a big silhouette and a small crouch turn paper into ground. In that compact space, a seventeenth-century artist practices a habit of attention that is still radical—treating strangers as worthy of exact notice. The sheet keeps its promise each time we return to it: we feel the day’s bite, we hear the mutter, and we recognize the unglamorous bravery of going on.