Image source: wikiart.org

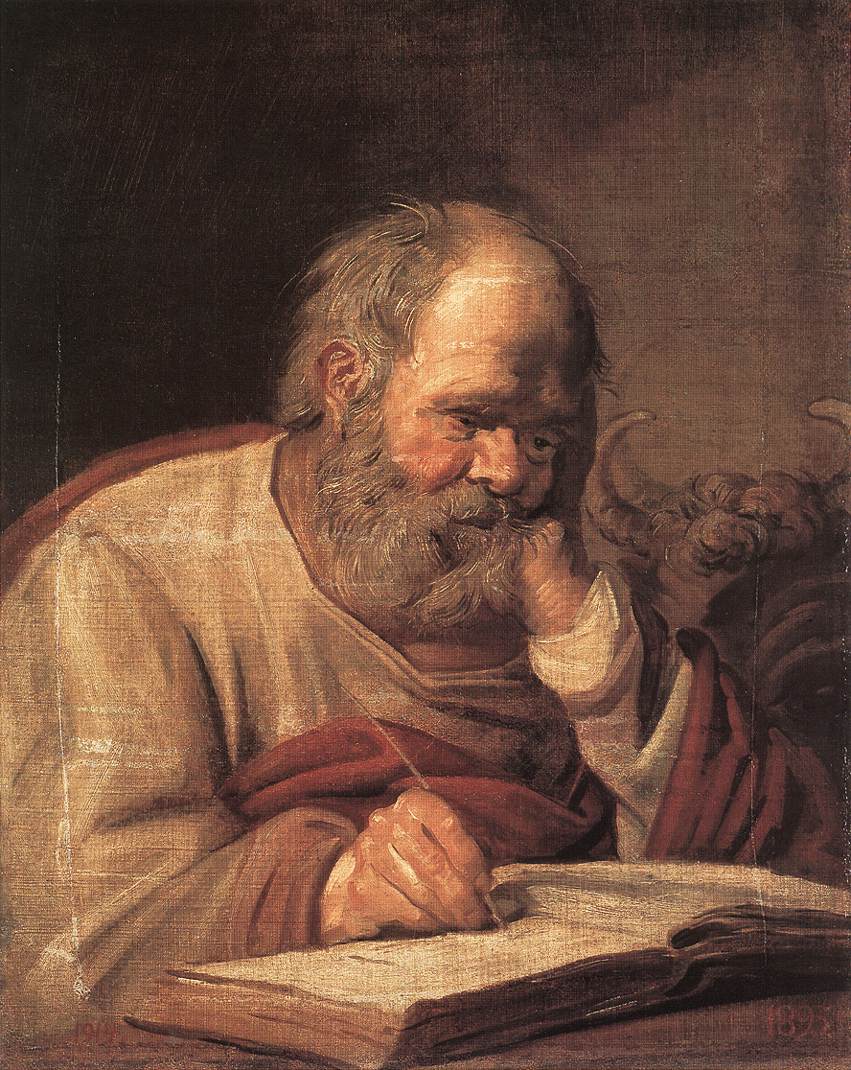

Meeting St. Luke in a Private Moment

Frans Hals’s St. Luke (1625) approaches a sacred subject in a way that feels strikingly human. Instead of presenting the evangelist as an untouchable emblem of authority, Hals offers an elderly man absorbed in work, leaning forward with the weight of thought in his posture. The scene is quiet, almost domestic. The saint’s holiness is not announced through spectacle; it is suggested through attention, patience, and the dignity of labor.

The painting’s emotional center is this sense of intimacy. We are brought close enough to read the gesture of the hand, the softness of the beard, the creases of age and concentration. The evangelist is not preaching or gesturing to a vision. He is writing. Hals makes the act of recording the Gospel feel like something that happens in real time, under a single light, in a room that might be ordinary except for the gravity of what is being formed on the page.

There is also a subtle invitation in how the figure turns inward. St. Luke does not perform for us. He does not seek the viewer’s agreement or admiration. He is turned toward the work, and we become witnesses. That choice transforms the viewing experience. Rather than confronting us, the painting draws us into the silence of composition, the slow accumulation of words, the private struggle to shape truth into language.

Composition and the Architecture of Concentration

The composition is built around a simple, persuasive structure: head, hand, and book. The saint’s face sits above the open pages like a lantern of thought, while the writing hand anchors the lower portion of the scene. Hals uses diagonal lines to create momentum: the angle of the arm, the slant of the desk or book, and the forward tilt of the torso guide the eye toward the act of writing. The saint appears to be caught in the middle of a sentence, paused for a heartbeat as if listening for the next phrase.

The figure occupies much of the frame, creating a sense of closeness. There is enough space to breathe, but not enough to turn the moment into a grand tableau. The background remains restrained, allowing the saint’s body and the luminous book to dominate. Even the chair and surrounding shapes feel secondary, present mainly to support the pose and the atmosphere.

The pose itself is carefully chosen. St. Luke rests his head on his left hand, a classic gesture associated with contemplation and study. In many images, this could read as melancholy. Here it reads as depth. The weight of the head suggests fatigue, age, and the long hours of mental labor, but the alertness of the eyes and the readiness of the writing hand keep the scene active. It is not despair; it is concentration.

The desk and book form a stage for that concentration. The open pages catch light and reflect it upward, illuminating the saint’s face and beard. This creates a visual logic that also becomes symbolic: the text is literally a source of light. Hals does not need to paint an angel or a halo to imply spiritual illumination. The act of writing, and the light it generates in the composition, does the work.

Light, Shadow, and the Mood of a Single Source

Light in this painting feels focused and local, as if coming from a window just out of view. It falls across the saint’s forehead, cheek, and beard, and pools on the pages of the book. The surrounding space remains subdued. This creates a mood of enclosure, the kind of atmosphere that makes a room feel hushed even during the day.

Hals uses shadow not only to model form but to protect the moment. The darker background and the deep tones around the figure keep the scene from feeling exposed. The saint is sheltered in shadow, while the essential elements are lit: face, hand, and page. The viewer’s attention is guided without force. The lighting feels natural and believable, which helps the sacred content feel grounded rather than theatrical.

The transitions between light and shade are handled with sensitivity. Hals does not smooth everything into a polished gradient. He allows paint to remain visible, and the light often appears in decisive touches rather than blended softness. This gives the illumination a living quality, as if it is flickering slightly with the movement of the subject or the shifting of the day.

The contrast between the bright book and the darker surroundings also creates a psychological effect. It makes the written word feel urgent and heavy. The pages seem almost too bright to ignore, a kind of visual demand. St. Luke’s posture, leaning into that brightness, reads as devotion shaped by effort.

The Face as a Record of Time

St. Luke’s face is one of the most compelling aspects of the painting. Hals renders age with honesty, but not cruelty. The skin shows wear, the cheeks are flushed, and the eyes carry the slight heaviness of years. Yet the expression is not simply tired. It is thoughtful, inward, and steady.

The beard becomes a major expressive tool. Hals paints it with a mixture of soft masses and sharper strokes, letting the texture suggest both fullness and looseness. This beard does not feel like a decorative prop. It feels like part of a living body, subject to time and gravity. In the same way, the thinning hair and the balding head are not hidden. They are integrated into the portrait’s truth.

The saint’s gaze is also intriguing. It does not lock onto the viewer. It appears to aim slightly downward and inward, toward the page or toward a mental space where sentences are formed. That gaze creates the sense that we have entered a moment already in progress. We are late arrivals, allowed to observe but not acknowledged.

This treatment of the face aligns with Hals’s broader interest in capturing the immediacy of a person rather than a static ideal. Even in a religious subject, he remains a portraitist of character. St. Luke is not reduced to an emblem. He remains a man who thinks, pauses, and continues.

Hands, Gesture, and the Physicality of Writing

The writing hand is painted with a careful balance of realism and painterly freedom. Hals understands that hands carry narrative. The saint’s right hand, holding the pen, is a tool of creation. Its placement and firmness communicate the seriousness of the task. The left hand, supporting the head, communicates endurance, the long duration of study.

The contrast between these hands is meaningful. One is active, the other is supportive. Together they describe the full body experience of intellectual labor: the mind pushing forward, the body bearing weight.

The pen itself, a small object, becomes a quiet axis of meaning. It is the instrument through which sacred text enters the world. Hals does not exaggerate it, but he ensures it is readable. The tip aligns with the pages, visually reinforcing the idea that the painting is about transmission, about turning thought into record.

The open book also matters as a physical presence. Its pages are thick and slightly uneven, with a sense of weight. This is not a symbolic book painted as a flat sign. It is a real object in space, a substantial volume that suggests authority and labor.

Color and the Warmth of Earthbound Spirituality

The palette is warm and restrained, dominated by browns, creams, and reds. These colors create a world that feels grounded and tactile. The saint’s clothing is rendered in pale tones that catch light gently, and the red fabric draped across him adds depth and warmth. This red is not merely decorative. It gives the figure a pulse, a sense of life within the quiet.

The background remains subdued, allowing the warmer notes to stand out. The overall harmony suggests a room lit by late afternoon light, where objects and flesh share a common atmosphere. Hals uses this harmony to avoid dividing the sacred from the ordinary. Everything belongs to the same world.

The cream and off white tones on the pages and sleeves echo each other, linking writing and body. The saint’s labor becomes part of his physical presence, not separate from it. The colors support the painting’s central claim: holiness can be expressed through ordinary materials and ordinary effort.

Brushwork and the Sense of a Living Surface

Hals’s brushwork is essential to how the painting feels. He often allows strokes to remain visible, and here that visibility enhances the subject. The paint describes fabric, beard, and skin without becoming overly finished. The texture of the surface suggests the texture of life, imperfect and immediate.

In the clothing, Hals uses broad strokes that imply folds and weight without counting every crease. The result feels natural. In the beard and hair, the strokes become more varied, sometimes soft and blended, sometimes quick and linear, creating a convincing sense of strands and volume.

The face is built from layered tones that model form while preserving liveliness. Highlights are placed strategically on the forehead and cheek, and the transitions are handled with confidence. Hals is not chasing porcelain smoothness. He is chasing presence.

Even the background, though quiet, is not empty. It has a worked surface, a subtle field of paint that keeps the air alive. This matters because it prevents the scene from becoming a cutout figure against void. St. Luke occupies a real atmosphere.

Iconography and the Evangelist’s Identity

St. Luke is traditionally associated with writing, both as an evangelist and, in later tradition, as an artist who painted the Virgin. This painting emphasizes the writer aspect. The saint’s task is the creation of text, the formation of a Gospel. Hals’s choice to focus on writing rather than on overt symbols suggests a preference for lived devotion over ceremonial display.

Many images of Luke include the ox, his symbolic animal, or an angelic presence. Here, such elements are not prominent. That absence is not a loss. It is a deliberate simplification that pushes the viewer toward the human core of the story. Luke becomes credible not because he is surrounded by signs, but because he looks like someone who could actually do this work.

The writing scene also carries broader meaning. It suggests continuity and tradition: sacred knowledge passed through hands, through books, through time. The saint’s age reinforces the idea of accumulated wisdom. His posture suggests that wisdom is not effortless. It is earned through hours, through bodily strain, through persistence.

Between Portrait and Sacred Image

One of the painting’s most fascinating qualities is its balance between portrait realism and religious subject. Hals treats St. Luke with the same observational intensity he might bring to a Haarlem sitter. The saint’s individuality feels intact. This approach makes the sacred story feel close to everyday experience.

At the same time, the painting does not become merely a genre scene of an old man writing. Its seriousness, lighting, and compositional focus elevate the moment. The open book becomes an altar of sorts, and the saint’s face becomes a site of inner attention. The religious meaning emerges through mood and structure rather than through explicit spectacle.

This balance reflects a broader strength in Dutch painting of the period, where spirituality could be conveyed through domestic interiors, stillness, and honest observation. Hals brings his own temperament to that tradition, emphasizing vitality and immediacy. Even in stillness, his paint feels alive.

The Emotional Tone: Quiet, Weighty, Human

The dominant emotion is quiet gravity. St. Luke appears absorbed, perhaps tired, but not defeated. There is tenderness in the way Hals paints the aged features. The saint’s humanity is not corrected or idealized away. It is honored.

The painting also carries a subtle sense of time. We feel the hours that have passed and the hours still to come. The posture implies a long session at the desk, and the weight of the head suggests the physical cost of sustained attention. This time sense makes the sacred task feel real. Writing becomes a form of devotion that requires endurance.

There is also a kind of companionship offered to the viewer. Many people recognize the experience of leaning on a hand while thinking, of pausing mid task to search for the right words. Hals connects that familiar experience with the figure of an evangelist. The result is an image that can feel comforting: the sacred is not distant, it is built through the same struggles of attention and effort that shape any serious work.

Hals’s Achievement in 1625

By 1625, Hals had already established a style known for liveliness, strong characterization, and confident paint handling. In St. Luke, he applies those strengths to a subject that could easily become stiff or overly solemn. Instead, he finds a stillness that remains vivid.

His achievement is not only technical, though the handling of light and texture is impressive. The deeper achievement is psychological. Hals makes the saint believable. He makes the act of writing feel like an act of being, not a staged emblem. The viewer is invited to respect the labor, the mind, and the body that carries the mind.

The painting also shows Hals’s ability to compress meaning. With a limited setting and a restrained palette, he creates a scene that feels complete. Everything points toward the central act. The viewer does not need additional symbols because the structure already speaks.

Conclusion: Sacred Meaning Through Ordinary Labor

St. Luke presents holiness as something that happens in a room, at a desk, through a hand that continues to write even when the head grows heavy. Frans Hals turns the evangelist into a living person whose authority is inseparable from effort and time. The warm light on the pages, the honest depiction of age, and the quiet intensity of the pose create an image that feels both intimate and weighty.

What remains with the viewer is not a dramatic miracle but a human truth: that words capable of shaping history are formed in private moments of concentration. Hals captures that truth with paint that stays visibly alive, reminding us that the sacred enters the world through physical acts, imperfect bodies, and persistent minds. The result is a painting that feels deeply respectful without being distant, and deeply human without losing spiritual gravity.