Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Francisco de Zurbaran’s Adoration of the Shepherds

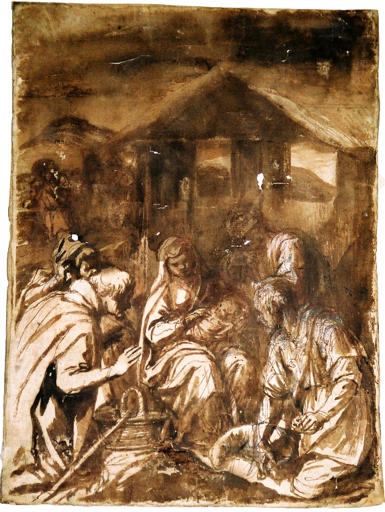

Francisco de Zurbaran is widely celebrated for his intensely spiritual altarpieces and his quiet, monumental depictions of monks and saints. “Adoration of the Shepherds” presents a different side of his art. Instead of a highly polished oil painting filled with rich colors, we encounter a monochrome work that looks like a rapid yet thoughtful study. Executed in brown ink and wash with touches of white heightening, it offers a glimpse into Zurbaran’s creative process while still functioning as a moving devotional image.

In this scene, a group of humble shepherds kneel before the newborn Christ. The figures gather in a tight circle around the Child and his mother, whose glowing presence becomes the center of both composition and meaning. Even though the work is unfinished and sketch like, Zurbaran’s command of light, gesture and storytelling is unmistakable.

Subject and Iconography of the Adoration

The Adoration of the Shepherds recounts the Gospel story in which angels announce Christ’s birth to shepherds watching their flocks by night. The shepherds hurry to Bethlehem, where they find the Child with Mary and Joseph in a stable. In Christian tradition, this episode symbolizes the recognition of Christ by simple, poor people before kings and scholars.

Zurbaran focuses on the intimate moment in which the shepherds first gaze on the infant Jesus. At the center sits Mary, cradling the Child in her lap. Joseph is placed nearby, either partially obscured or leaning in toward the group. Around them kneel at least three shepherds. One holds a staff, another may carry a simple gift, and a third bows deeply in reverence. In the dim background a rustic hut or stable frames the group, while faint suggestions of landscape and secondary figures appear beyond.

By stripping away elaborate architecture or crowds of angels, Zurbaran concentrates on human presence. The gestures of the shepherds, their bent backs and extended hands, express astonishment and devotion more eloquently than a multitude of decorative details.

The Monochrome Technique and Preparatory Character

Unlike the richly colored Zurbaran altarpieces found in many churches, this work is executed entirely in shades of brown, sometimes called a bistre or sepia wash. The artist uses a combination of ink outlines, diluted washes and areas of white body color to create form and light. This approach gives the image the feeling of a drawing rather than a finished painting.

Such monochrome works often served as preparatory studies or modello designs for larger altarpieces. They allowed the artist to plan the arrangement of figures, the distribution of light and shadow and the general emotional rhythm of a composition. In “Adoration of the Shepherds,” we see how Zurbaran experiments with overlapping silhouettes and the placement of the stable structure behind the group.

The unfinished surface, with visible brushstrokes and areas of bare paper, creates a raw immediacy. Instead of polished detail, we experience the freshness of the artist’s first ideas. The brown tone unifies the scene, almost like the warm glow of candlelight. It invites viewers to supply the missing colors in their imagination, making the act of looking more active and contemplative.

Light, Shadow and Spiritual Focus

Even in this sketch like form, Zurbaran’s sense of chiaroscuro is powerful. The primary source of light seems to fall from above and slightly to the left, illuminating the Virgin and Child and the faces of the nearest shepherds. Their robes catch strong highlights, while the hut and distant figures sink into darkness.

This pattern of illumination has a clear spiritual meaning. The brightest area is concentrated around the infant Christ, whose small body radiates light outward to the surrounding adults. Mary’s face is gently lit, her features soft and calm. The shepherd nearest to the viewer bends toward the light, his rugged clothing catching bright streaks. Another shepherd, partially in shadow, leans in with a mixture of awe and hesitancy.

The background remains comparatively dark and indistinct. This contrast isolates the holy group in the foreground, as if the rest of the world is fading into obscurity while the miracle of the Nativity unfolds. The effect is contemplative rather than theatrical. Light does not explode across the surface but quietly carves out forms, directing our attention to the center of devotion.

The Composition and Arrangement of Figures

Zurbaran organizes the scene around a triangular configuration. At the apex of the triangle sits Mary with the Child in her lap. The base of the triangle is formed by the kneeling shepherds and one seated figure in the foreground. This classical structure gives the group stability and harmony, echoing the traditional Holy Family compositions of Renaissance art while retaining Zurbaran’s own sober mood.

The hut in the background frames the central group like a shallow stage set. Its dark interior arch mirrors the curve of Mary’s body and creates a niche around her. The roofline runs horizontally, anchoring the composition and separating the sacred foreground from the hazier landscape beyond.

Diagonal lines add subtle movement. The staff of a shepherd, the angle of another’s back and the slope of Mary’s arm all draw the eye toward the Child. Even when parts of the drawing appear rough, these lines reveal a carefully calculated structure that guides the viewer’s gaze.

The Shepherds as Human Witnesses

One of the strengths of Zurbaran’s religious images is his ability to dignify ordinary people. In this “Adoration of the Shepherds,” the rustic visitors are portrayed with a mix of realism and reverence. Their garments are simple cloaks and tunics, rendered with a few broad strokes. Yet their faces, even when barely defined, convey concentration, humility and astonishment.

The shepherd in the left foreground kneels with one knee raised, leaning on his staff. His head is turned toward the Child, and his gesture suggests both offering and self presentation. He comes as he is, with his tools and rough clothing, yet he is fully welcomed into the sacred space.

The figure at the lower right, seated or kneeling, bends forward in a posture of deep respect. His shoulders are rounded and his head inclined, as if overwhelmed by the sight before him. Another shepherd slightly behind may clasp his hands or clutch a small gift. Through these varied poses, Zurbaran creates a mini drama of responses to the divine: awe, gratitude, curiosity and devotion.

The Holy Family at the Center

Mary sits quietly at the center of the group, her body forming a gentle curve around the sleeping or resting Child. In this drawing she is not heavily idealized. Her face is modest and serene, her robes simple in design. The sense of motherly tenderness is strong, even though the outlines are loose. She cradles the infant carefully, turning slightly toward the shepherds so they can see him, while still keeping him close.

Christ appears as a small bundle in her arms, rendered with a few swift strokes of light wash. Despite the simplicity, his role as the focus of attention is unmistakable. Every line in the composition seems to bend or tilt toward him.

Joseph, often shown as an older man, may be the figure standing or seated just behind Mary, perhaps to the right. Even if only faintly indicated, he acts as a stabilizing presence, a guardian who watches over the group. Zurbaran frequently portrayed Joseph with quiet dignity rather than dramatic gestures, and that attitude seems consistent here.

Architectural and Landscape Setting

Behind the main group rises a crude shelter, likely representing the stable at Bethlehem. It consists of simple posts and a sloping roof, perhaps made of rough boards or thatch. In keeping with the sketch like nature of the work, Zurbaran suggests rather than details the building. The structure serves three purposes. It situates the scene in a recognizably humble environment, it frames the holy figures, and it provides a dark backdrop that enhances the light on the foreground group.

Beyond the hut, faint horizontal strokes suggest a distant town or hillside. These elements are very understated, almost ghostlike. They remind us that the Nativity took place within a broader world, yet they never compete with the intimacy of the immediate group.

The ground at the bottom of the image is indicated by a few curved lines and patches of wash. Perhaps we can make out a basket, a bundle of belongings or the simple gifts that the shepherds have brought. Zurbaran’s restraint keeps the scene uncluttered and focused.

Devotional Atmosphere and Emotional Tone

Despite its preparatory character, “Adoration of the Shepherds” carries a strong devotional atmosphere. The close clustering of figures, the warm brown tonality and the hushed gestures create a sense of quiet reverence. It is as if we have entered the stable with the shepherds and are sharing their first glimpse of the Child.

The absence of brilliant color actually heightens this feeling. Without visual distractions, we concentrate on posture and gesture. The bowed heads and folded hands encourage viewers to adopt a similar attitude of inward adoration. Zurbaran’s subdued approach is in harmony with the spiritual ideals of Spanish Counter Reformation piety, which valued humility, simplicity and deep interior prayer.

At the same time, there is a gentle warmth running through the scene. Mary’s protective embrace, the shepherds’ earnest curiosity and the compact shelter all suggest a community formed around the newborn Christ. The mood is not tragic or foreboding but quietly joyful, emphasizing the human tenderness of the Nativity.

Zurbaran’s Artistic Method Revealed

Works like this are especially valuable because they reveal how Zurbaran’s grand altarpieces were built from initial sketches. In “Adoration of the Shepherds,” we can see him testing the balance between figures, adjusting the tilt of heads and the flow of drapery. Areas that appear overworked, with thicker patches of wash or corrections in white, indicate where he changed his mind or strengthened a shadow.

For students of Baroque art, the drawing offers insight into how a painter known for his still, monumental imagery first conceived those compositions. The energy and looseness of the brushwork show that his seemingly frozen altarpieces began as experiments full of movement.

This piece also demonstrates Zurbaran’s reliance on light as an organizing principle. Instead of starting with precise line drawing and then applying color, he seems to think in terms of illuminated masses, sculpting the scene through tonal values. That habit helps explain the powerful chiaroscuro of his finished canvases.

Place Within Zurbaran’s Oeuvre and the Baroque Tradition

The theme of the Adoration of the Shepherds appears several times in Zurbaran’s career, and more broadly it was a favorite subject among Spanish Baroque painters. It allowed artists to combine humble realism with spiritual drama: weathered shepherds, rustic animals and rough architecture illuminated by a miraculous child.

Compared to more theatrical interpretations by some contemporaries, this monochrome version is remarkably restrained. There are no swirling angels or luxurious fabrics, only simple figures and a wooden shelter. Yet its very simplicity places it close to the heart of Zurbaran’s art. He excelled at making holiness visible in quiet, ordinary forms, whether in the face of a monk, the folds of a habit or the surface of a rough wooden table.

Seen today, “Adoration of the Shepherds” bridges the gap between drawing and painting, between preparatory sketch and finished devotional work. It invites us not only to admire Zurbaran’s skill but also to imagine the larger altarpiece it may have inspired, perhaps filled with rich colors yet still grounded in the intimate, humble vision we see here.

Conclusion

“Adoration of the Shepherds” by Francisco de Zurbaran is far more than an unfinished study. In its warm monochrome palette, concentrated light and quietly expressive figures, it captures the essential meaning of the Nativity story. The humble shepherds who first received the news of Christ’s birth gather with Mary and Joseph around the Child, forming a circle of reverent attention.

Through swift brushstrokes and subtle gradations of tone, Zurbaran shapes a narrative of faith recognized by simple hearts. The rustic shelter and faint landscape suggest the poverty of Bethlehem, while the luminous center conveys the presence of divine grace. Even without the artist’s usual rich colors, the image pulses with spiritual life.

For modern viewers, this work offers a unique glimpse into Zurbaran’s workshop and imagination. It shows how a great Baroque painter thought through composition, light and gesture before committing himself to a finished canvas. At the same time, it stands alone as a meditation on humility, wonder and the quiet joy of the first Christmas night.