Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Christ Crucified

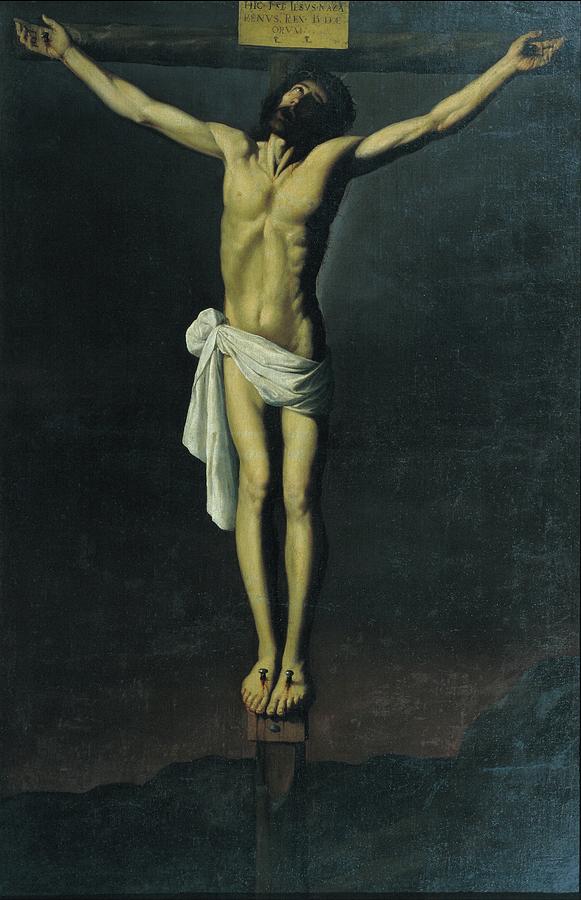

“Christ Crucified” by Francisco de Zurbaran is one of the most concentrated and solemn depictions of the crucifixion in Spanish Baroque art. The painting shows Christ alone on the cross against a dark, nearly featureless background. His body hangs in a graceful yet agonized curve, lit by a focused light that reveals every muscle, vein, and wound. There are no onlookers, no landscape details, and no narrative accessories, only the solitary figure of the crucified Savior suspended in a vast, shadowy space.

Through this radical simplicity Zurbaran transforms a familiar subject into a powerful object of contemplation. The viewer is invited to stand before the cross with nothing to distract the eye or the heart. Every element in the composition, from the pose of Christ’s body to the handling of light and color, directs attention toward the mystery of sacrificial love.

Zurbaran and the Spanish Vision of the Crucifixion

To understand the force of this painting it helps to place it within Zurbaran’s context. Working in seventeenth century Spain, he served a culture shaped strongly by the Catholic Reformation. Art was expected to nourish devotion, clarify doctrine, and engage the emotions of viewers in a direct and honest way. Spanish patrons favored images that were sober, intense, and rooted in the experience of prayer.

Zurbaran made his name through paintings of monks, martyrs, and saints, rendered with striking realism and deep spiritual gravity. His Christ figures share these qualities. Rather than treating the crucifixion as a distant historical event, he brings it close, presenting Christ as a living, suffering presence.

At the same time, his restrained style distinguishes him from more theatrical contemporaries. Where other Baroque artists multiplied figures and gestures, Zurbaran often removed everything that did not serve his meditative purpose. “Christ Crucified” is among the clearest expressions of this approach.

The Isolated Figure and the Vertical Composition

The first thing the viewer notices is the stark isolation of Christ. He fills the vertical format of the canvas, his outstretched arms almost touching the frame. The crossbar near the top and the vertical beam running down the center create a monumental cruciform shape that organizes the entire composition.

Christ’s body hangs slightly forward, forming a gentle S curve. The head tilts downward, the chin resting on the chest, and the hips twist slightly, with one leg crossing over the other. This pose combines classical ideals of beauty with the reality of suffering. The figure is both graceful and heavy, as if pulled by the weight of pain and gravity.

Beneath the feet, the rocky ground is barely visible, rendered in deep shadow. Above and around the cross spreads a vast field of dark blue gray. There is a sense of cosmic emptiness, as though all creation were holding its breath at the moment of death. The emptiness also has a practical effect. With no secondary elements for comparison, the viewer feels the full height and vulnerability of the suspended body.

Light, Shadow, and the Presence of Mystery

Zurbaran’s use of chiaroscuro in this painting is masterful. A concentrated light, perhaps imagined as moonlight or a supernatural glow, falls from the upper left. It strikes Christ’s chest, abdomen, arms, and thighs, leaving other parts in deep shadow. The result is a sculptural modeling of the body. Muscles and tendons stand out clearly, yet the light is soft enough to maintain the delicate texture of skin.

The face is partly concealed in shadow, especially the eyes, which disappear beneath the brow and beard. This obscurity lends an air of mystery and reverence. The viewer senses suffering and abandonment, but also a hidden, unspoken communication between Christ and the Father that remains beyond human sight.

The background is almost entirely dark, with only subtle variations near the horizon line. This darkness functions symbolically as the shadow of sin and death, which Christ enters fully on the cross. At the same time, it frames his illuminated body like a precious object emerging from a night sky. Light and darkness meet in the figure of Christ, suggesting that through his death divine light penetrates human darkness.

Anatomical Realism and Spiritual Ideal

One of the striking features of “Christ Crucified” is the careful anatomically informed depiction of the body. The ribcage is clearly defined, the abdominal muscles taut, and the knees and ankles rendered with precision. The artist’s study of life models and perhaps of sculptural prototypes is evident.

Yet this realism is guided by spiritual purpose. The body is idealized in its proportions and purity. Christ appears lean but not emaciated, strong yet clearly suffering. The skin is smooth, unmarred by any sign of decay. This combination of beauty and pain expresses the paradox of the crucifixion, where humiliation and glory meet.

The wounds in the hands and feet are visible but not exaggerated. Blood flows minimally, in thin rivulets. Zurbaran avoids sensationalism, choosing instead a restrained depiction that encourages quiet sorrow rather than shock. The crown of thorns is present yet partially obscured by shadow, again suggesting that the physical torment, though real, is only one aspect of the deeper spiritual sacrifice.

The Loincloth and the Question of Modesty

A key element in Zurbaran’s crucifixion is the white loincloth that wraps around Christ’s waist. Painted with broad, confident strokes, the cloth gathers in a knot at the side and falls in a vertical fold. Its bright whiteness contrasts sharply with the warm flesh tones and the dark background.

Symbolically, the cloth speaks of purity, innocence, and the voluntary poverty of Christ. It also addresses the demands of modesty in a devotional image intended for worship. Yet Zurbaran uses it to accentuate the vertical movement of the composition. The fold of fabric visually connects the torso with the legs, guiding the viewer’s eye downward, then back up along the body.

The simplicity of the cloth reinforces the overall austerity of the painting. There are no decorative patterns or complex folds, only a straightforward garment that serves both physical and symbolic needs.

The Inscription and the Historical Anchoring of the Scene

At the very top of the cross is a small plaque with the abbreviated inscription that identifies Jesus as “King of the Jews.” Even though the letters are hard to read from a distance, their presence anchors the painting in the Gospel narrative. This is not an abstract figure but the crucified Jesus of Nazareth condemned under Roman authority.

The plaque also reminds viewers that Christ’s kingship is revealed precisely in his apparent defeat. The irony of the title, meant as a mockery by the authorities, becomes for believers a proclamation of truth. In the context of Zurbaran’s Spain, where royal imagery was familiar, the crucified King offered a model of humble yet absolute sovereignty.

Emotional Impact and Devotional Purpose

“Christ Crucified” was created not simply as a work of art but as an aid to prayer. Its emotional impact arises from the way it encourages viewers to stand in silent presence before Christ. With no crowd of mourners or executioners, each viewer feels addressed personally by the sacrifice.

The lowered head and closed eyes of Christ suggest both death and prayer. He appears at once abandoned and serene. The slight twist of the torso and the tension in the arms communicate pain, yet the overall stillness of the figure gives a sense of consummation, as if the drama of the passion has resolved into a final offering.

Viewers are invited to enter into this moment, to consider the cost of love and the depth of mercy. The painting does not dictate a specific emotional response. Some may feel sorrow, others gratitude, others awe. But its stripped down language ensures that whatever response arises is focused directly on Christ rather than on secondary narrative details.

Symbolic Reading of the Vertical Axis

If one reads the painting symbolically, the vertical axis of the cross can be seen as a bridge between heaven and earth. At the top, near the inscription, the crossbar touches the upper frame, pointing beyond the visible world. At the bottom, the vertical beam plunges into the dark rocky ground, firmly planted in human history and suffering.

Christ’s body occupies this axis fully. His head is nearer the realm of heaven, his feet near the earth, and his open arms span the space between. This configuration visually expresses the role of Christ as mediator, uniting divine and human. It also suggests a cosmic embrace, as if his outstretched arms gather all creation into the saving act of the cross.

The darkness that surrounds the lower part of the painting can be understood as the realm of sin, ignorance, and death. As the viewer’s eye moves upward along the body, the light intensifies until it reaches the chest and upper torso, where the illumination is strongest. This upward movement can be read as a path from darkness to light made possible through the crucifixion.

Comparison with Other Crucifixions

When compared with other famous crucifixion images, such as those by Velázquez or Flemish painters, Zurbaran’s painting stands out for its extreme minimalism. Many works include elaborate landscapes, angelic witnesses, the Virgin and Saint John, or symbolic details like skulls and bones at the foot of the cross. In “Christ Crucified” all such additions are omitted.

This simplicity aligns with the spirituality of certain religious orders, especially those that valued silence, poverty, and interior prayer. In a monastic setting, such a painting would create a visual space similar to a cell or a chapel, where the monk faced Christ alone.

The choice of a nearly monochrome background also distances the image from theatrical Baroque scenes filled with clouds, rays, and heavenly hosts. Zurbaran’s crucifixion is more introspective. It invites extended, quiet looking rather than quick emotional excitement.

Contemporary Resonance of the Painting

For modern viewers, “Christ Crucified” has a surprising contemporary feel. Its large empty areas, limited color palette, and focus on a single figure echo some aspects of modern minimalism. The painting’s refusal of sentimentality and decorative excess may resonate with audiences accustomed to clean, uncluttered visual design.

At the same time, the work confronts present day viewers with a stark image of vulnerability. The exposed body, nailed and suspended, can evoke compassion beyond specifically religious contexts. It may recall victims of injustice, torture, and violence in every era. The painting thus opens a path for reflection on suffering and solidarity, even for those who do not share Christian beliefs.

For believers, the piece continues to function as a powerful reminder of the central mystery of their faith. Its realism emphasizes that the crucifixion is not a myth but an event that involved a real human body. Its contemplative tone encourages personal appropriation of that event as a source of hope and transformation.

Conclusion A Monument of Silent Sacrifice

“Christ Crucified” by Francisco de Zurbaran is a monument of silent sacrifice and concentrated devotion. Through a solitary figure on a dark background, the painter distills the vast narrative of the passion into a single moment of arresting stillness. The disciplined composition, careful anatomy, sensitive light, and symbolic details all work together to reveal the cross as both an instrument of death and a sign of redeeming love.

The painting is not an illustration that explains everything. Instead, it establishes a relationship between the viewer and the crucified Christ. Standing before it, one senses both the weight of human suffering and the depth of divine compassion. The emptiness around the cross becomes a space where the viewer’s own questions and prayers can arise.

Centuries after its creation, the work retains a powerful presence. It demonstrates how art can serve as a bridge between history and contemplation, between physical reality and spiritual meaning, between the solitude of an individual and the universal drama of salvation. In its stark simplicity, “Christ Crucified” continues to speak with a voice that is quiet yet impossible to ignore.