Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Saint Francis in Meditation

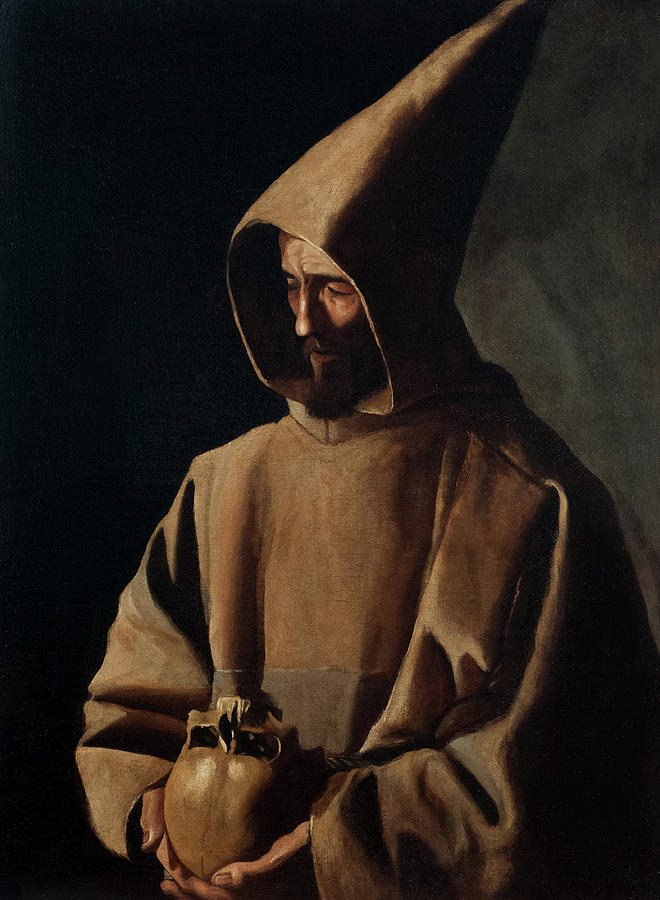

Francisco de Zurbaran’s painting “Saint Francis in Meditation” is one of the most intense and concentrated images of spiritual contemplation in seventeenth century Spanish art. A solitary friar stands against a voidlike background, wrapped in a rough brown habit that swallows his figure in shadow. The pointed hood, pulled forward over his head, partially conceals his features. He looks downward, absorbed in thought, while his hands gently cradle a human skull.

Nothing else breaks the silence of the scene. There is no landscape, no accessory furniture, no shining halo. Yet the painting vibrates with a sense of interior life. Through the humble body of Saint Francis of Assisi, Zurbaran evokes questions about mortality, humility, and the search for God. In a single cloaked figure and a skull, he builds a whole world of devotion.

Saint Francis and Spanish Counter Reformation Spirituality

Understanding the spiritual atmosphere behind the painting helps explain its powerful simplicity. Saint Francis of Assisi, founder of the Franciscan order, was revered in Catholic Europe as a model of radical poverty and Christlike compassion. He renounced wealth to live among the poor, preached to ordinary people, and sought an intimate, personal relationship with Christ.

In seventeenth century Spain, the Catholic Church was deeply shaped by the Counter Reformation. Art was expected to encourage piety, instruct the faithful, and stir the heart to devotion. Spanish artists did this not through lavish spectacle, but through sober intensity and emotional truth. Saint Francis, with his emphasis on humility and identification with the suffering Christ, became a favored subject for painters like Zurbaran.

Depicting Francis holding a skull fits perfectly with this spiritual climate. The image reminds viewers that life is short and worldly glory fragile, and that the true destination of the soul lies beyond death. Yet the mood is not despairing. Instead, the friar’s calm face and gentle hands convey a peaceful acceptance, as if he has already found in Christ the answer to the terror of mortality.

Composition and the Power of Restraint

The composition of “Saint Francis in Meditation” is strikingly economical. The figure is placed slightly to the right of center, filling most of the vertical format. He is shown from the knees up, oriented in three quarter view, his face turned down toward the skull he holds at chest level.

The left side of the canvas is almost entirely black. This deep, unmodulated darkness is not merely empty space. It functions like a backdrop that pushes the friar forward, isolating him from any concrete environment. The viewer’s eye has nowhere else to go. We are compelled to face Francis and the object of his contemplation.

On the right, a lighter, more varied patch of background appears behind the shoulder and hood, suggesting a wall catching faint light. This creates a subtle diagonal that moves from the dark void on the left, through the illuminated habit and face, toward the slightly lighter area on the right. The result is a sense of quiet movement, as if the monk’s interior gaze were drawing him out of shadow toward spiritual illumination.

This severe compositional restraint heightens the emotional impact. The entire world of the painting consists of three elements: the monk, the skull, and the darkness. Zurbaran trusts that these few elements are enough to carry a profound spiritual message.

Chiaroscuro and the Theater of Light

Light is a key protagonist in this painting. A strong, focused light source enters from the upper left, striking the front of the hood, the bridge of the nose, the cheek, and the hands that hold the skull. The rest of the figure falls gradually into shadow, with the cowl’s interior almost swallowing the upper part of the face in darkness.

This use of chiaroscuro, reminiscent of Caravaggio yet adapted to Zurbaran’s more contemplative temperament, creates a sense of drama without movement. Light seems to reveal not only physical surfaces but spiritual states. The illuminated planes of the habit emphasize its coarse texture and simple folds, while the shadowed areas hint at the mysterious depths of Francis’s inner life.

The skull, although also in shadow, receives a glancing highlight that picks out its rounded form and hollow eye sockets. It appears almost like a small, mute interlocutor, catching the same light that reveals the saint’s features. Light therefore binds the living and the dead together in a single field, announcing both the inevitability of death and the possibility of grace that shines upon it.

The Habit as a Second Skin

Zurbaran, famous for his ability to paint fabric, gives the Franciscan habit a palpable presence. The heavy wool robe falls in straight, simple folds. The large sleeves and wide shoulders make the figure appear both massive and modest, as if the garment were more important than the body it covers.

The pointed hood is particularly striking. Its long peak rises up and back, creating a dramatic silhouette. Yet the inside of the hood remains dark, framing the saint’s face and drawing attention to the small zone where light reveals human flesh. The viewer senses that the monk has withdrawn deeply into the protective shell of his habit, a visual metaphor for retreat from worldly distractions.

The dull, earthy brown of the robe underscores the Franciscan vow of poverty. There are no decorations, no cords with elaborate knots, no color beyond variations of brown and warm gray. The very monotony of the fabric invites contemplation. In its folds we see a life stripped of luxury, focused entirely on prayer, penance, and service.

The Skull and the Theme of Memento Mori

At the heart of the painting’s symbolism lies the skull cradled in Francis’s hands. In Christian art, skulls serve as memento mori, reminders that all human beings will die. They urge viewers to evaluate their lives in light of eternity rather than temporary pleasures.

In “Saint Francis in Meditation,” the skull is not a frightening object. It is held gently, almost tenderly, in the saint’s palms. His fingers wrap around its sides with the care one might give a precious relic. This gesture suggests that he is not recoiling from death but accepting it as a truth that must be embraced.

The skull’s placement at chest level, close to the heart, reinforces this introspective meaning. It is as if Francis is holding death before his own heart, measuring his desires against the reality of mortality. He appears to ask: How should I live, knowing that I will die? For a Franciscan, the answer lies in embracing humility, poverty, and love of Christ. The painting becomes a visual sermon inviting the viewer to participate in the same meditation.

The Expression and Inner Life of Saint Francis

Because so much of the composition is taken up by the habit and dark background, the viewer is drawn to the small area of exposed face. Zurbaran portrays Francis with a long nose, narrow cheeks, and a short, trimmed beard. His eyes are lowered, barely visible beneath the shadow of the hood, and his lips are closed in a neutral, almost melancholic line.

This subdued expression speaks volumes. There is no theatrical ecstasy, no tearful anguish, no dramatic gesture toward heaven. Instead, the saint appears deeply absorbed, as if listening to an interior voice or holding an intense yet silent conversation with God.

The slight downward angle of his head adds to the impression of humility. He does not appear to seek attention. The viewer has the sense of intruding on a private moment of prayer. The respectful distance encouraged by the darkness around him mirrors the respect that contemplative life commands.

Yet the face is not severe. The soft light on the cheek and brow reveals warmth and humanity. We sense that Francis is compassionate, not harsh. His contemplation of death is not a morbid fascination but a pathway to deeper love and understanding.

Zurbaran’s Unique Approach to Franciscan Imagery

Many artists before Zurbaran had depicted Saint Francis, often emphasizing the dramatic miracle of the stigmata, where the saint receives the wounds of Christ in his hands, feet, and side. Such images typically include angels, crosses, or beams of light descending from heaven.

Zurbaran’s approach is more austere and psychological. Rather than showing a moment of miraculous intervention, he shows a moment of silent meditation. The miraculous is interior rather than exterior. This emphasis reflects Spanish mysticism of the period, deeply influenced by figures like Saint Teresa of Avila and Saint John of the Cross, who wrote about the soul’s dark night and the silent encounter with God.

In Zurbaran’s hands, Saint Francis becomes a kind of every believer. Stripped of external signs of sainthood, he appears as a simple monk wrestling with the same existential questions that face all humans. That universality is one reason the painting still speaks so strongly to modern viewers.

Dialogue Between Darkness and Light

Beyond individual symbolism, the painting can be read as a visual meditation on the relationship between darkness and light. The dark void that surrounds Francis may represent the unknown, the mystery of God, or the uncertainties of life. The light that strikes him suggests grace, revelation, and truth.

The friar stands at the threshold between these two realms. Part of his body fades into shadow, while another part is clearly illuminated. The skull, too, participates in this dynamic. In a sense, the painting states that only through confronting darkness, particularly the darkness of death, can one fully receive the light of divine understanding.

This interplay is calculated with great care. There is enough detail to keep the figure real and tangible, yet enough shadow to preserve a sense of mystery. The painting thus avoids both sentimental clarity and obscure abstraction. It mirrors the spiritual journey, where moments of insight alternate with stretches of obscurity.

Relevance for Contemporary Viewers

Although created in the context of seventeenth century Catholic Spain, “Saint Francis in Meditation” retains a compelling relevance today. In a world marked by constant noise, rapid communication, and entertainment, the image of a solitary figure in deep silence is striking. The painting invites viewers to rediscover the value of contemplation, of stepping back from distractions to reflect on life’s ultimate questions.

The skull, too, speaks to modern anxieties about mortality, especially in times of crisis or global uncertainty. Zurbaran does not deny the harshness of death, yet he shows it held calmly in human hands. The painting suggests that acknowledging mortality need not lead to despair. Instead, it can encourage a more meaningful, compassionate, and focused way of living.

Saint Francis’s humble habit also challenges contemporary ideals of status and display. In a culture that often prizes wealth and visibility, the painting presents a counter ideal: a life stripped down to essentials, where the greatest richness lies in spiritual depth rather than in external possessions.

Conclusion A Silent Icon of Interior Prayer

“Saint Francis in Meditation” is a masterpiece of concentrated emotion and spiritual reflection. With minimal elements, Francisco de Zurbaran creates a powerful image of a soul turned inward toward God. The heavy brown habit, the pointed hood, the gently cradled skull, and the quiet face illuminated against a sea of darkness all work together to express themes of mortality, humility, and contemplative search.

Rather than dazzling the viewer with narrative complexity or decorative excess, the painting commands attention through silence, emptiness, and light. It stands as a visual companion to the writings of Spanish mystics and to the Franciscan ideal of radical poverty and love for Christ.

Centuries after its creation, the painting still offers a place of visual retreat. To stand before it is to be invited into the same meditation as Saint Francis: to consider the fragility of life, to let go of unnecessary attachments, and to seek a deeper communion with the divine in the quiet of the heart.