Image source: wikiart.org

St Bonaventure in Prayer Before a Heavenly Choice

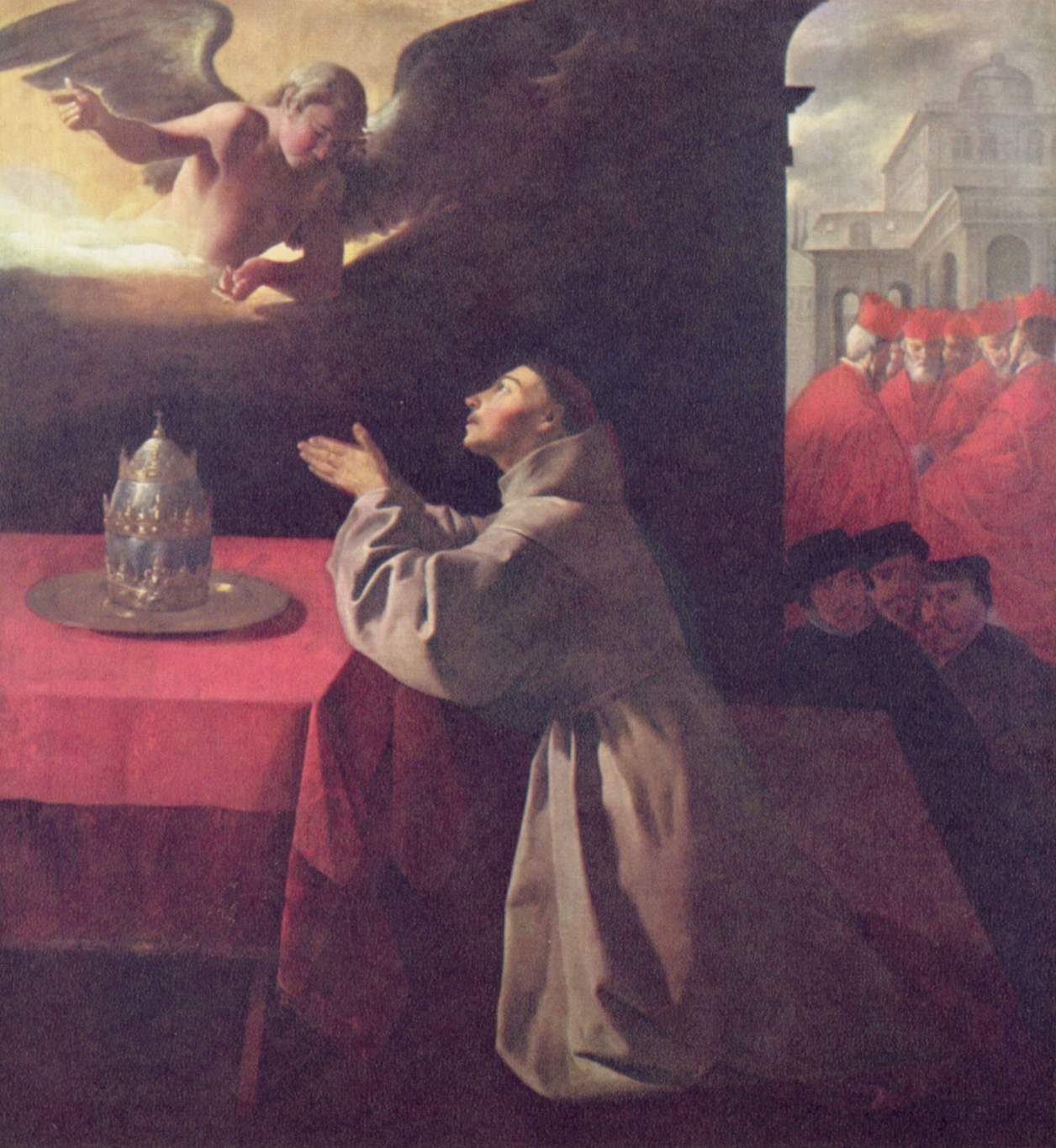

Francisco de Zurbaran’s “St. Bonaventure,” painted around 1650, offers a contemplative vision of one of the most respected theologians of the Middle Ages. Rather than portraying Bonaventure in a crowded academic setting, Zurbaran chooses a quiet, charged moment of prayer. The Franciscan saint kneels before a table draped in deep red, hands folded, eyes raised toward an angel emerging from luminous clouds. On the table rests the papal tiara, symbol of supreme authority, placed on a silver platter as if being presented to him.

In the shadowed background, a group of cardinals dressed in brilliant scarlet stand near a monumental church, observers of the scene yet distant from Bonaventure’s inner drama. By setting this humble friar between the earthly power of the Church and the direct voice of heaven, Zurbaran turns his canvas into a meditation on vocation, humility and divine election.

The Story Behind Zurbaran’s “St. Bonaventure”

Bonaventure, born Giovanni di Fidanza in the thirteenth century, joined the Franciscan order and became one of its greatest theologians and leaders. He was eventually created cardinal and bishop of Albano, gaining immense influence in the Church while remaining personally devoted to poverty and simplicity. Later traditions relate that he was considered as a candidate for the papacy, but out of humility and obedience he refused, preferring to serve as a Franciscan rather than as pope.

Zurbaran’s painting appears to reference this episode. The papal tiara on the table and the gathering of cardinals suggest an impending election. Yet the saint is not engaged in political maneuvering; he is entirely turned toward the angelic messenger. The composition thus dramatizes a spiritual choice: whether to accept the highest worldly office or to remain faithful to a vocation shaped by the Franciscan spirit.

For seventeenth century viewers in Catholic Spain, Bonaventure represented an ideal combination of learning and holiness. He was a scholar whose writings nourished mystical devotion and a leader who placed submission to God above ambition. Zurbaran distills these qualities into a single moment of intense prayer.

Composition and the Division of Space

The canvas is divided into two main zones. On the left, a red draped table extends toward the viewer, occupying much of the foreground. Bonaventure kneels beside it, his gray habit forming a triangular mass that firmly grounds the composition. Above him, the angel bursts forth from a glowing cloud.

On the right, separated by a dark architectural wall, stands the group of cardinals and the façade of a church bathed in soft daylight. They are placed at a distance, their red robes forming a block of color that echoes the tablecloth yet remains secondary to the emotional center. This separation between foreground and background, between solitary prayer and public life, reinforces the theme of inner discernment versus external expectations.

The diagonal line formed by Bonaventure’s body and raised gaze leads directly toward the angel’s outstretched arm. This strong diagonal gives the otherwise quiet scene a sense of movement and spiritual tension. The viewer’s eye follows the same path, moving from the tiara on the table, up through the saint’s clasped hands and face, to the heavenly messenger whose gesture carries divine instruction.

Light, Shadow and the Atmosphere of Revelation

As in many of Zurbaran’s works, light plays a crucial narrative role. The left side of the painting, where Bonaventure and the angel appear, is suffused with a warm, golden illumination. The angel’s body seems to be carved out of light, emerging from a cloud of radiance that spills over the tabletop and gently touches the saint’s habit.

In contrast, the right side with the cardinals and church is lit more coolly and evenly, as if under ordinary daylight. The difference in lighting subtly suggests that the true drama is happening between Bonaventure and the angel, in a supernatural sphere, while the ecclesiastical gathering remains on the level of earthly affairs.

Chiaroscuro heightens the sense of mystery. Bonaventure’s robe and the massive wall behind him sink into deep shadow, from which his illuminated face and hands emerge. This contrast symbolizes his interior life: the world around him may be dark or uncertain, but his attention is fixed on the source of light. The papal tiara itself catches highlights on its metallic surfaces, shimmering like an object of great allure, yet its gleam is less intense than the glow surrounding the angel.

The Figure of St Bonaventure

Zurbaran portrays Bonaventure as a relatively young friar, kneeling with both knees firmly planted on the ground. His gray Franciscan habit is voluminous, its folds rendered with heavy, sculptural realism. The rough material suggests poverty and simplicity, yet the way it is painted conveys dignity and weight.

The saint’s hands are joined in prayer, fingers extended upward. His expression is one of absorbed attention rather than ecstasy. His mouth is slightly parted, his eyes lifted, conveying the sense that he is listening as much as speaking. This listening posture is crucial. Bonaventure is not dramatically resisting the tiara; he is asking what God desires.

The positioning of his body near the table and the tiara hints at the nearness of the temptation. The symbol of ultimate ecclesiastical power is within arm’s reach. Yet his body angles away from it, oriented instead toward the angel. The contrast between his humble habit and the opulent headpiece summarizes the choice he faces.

The Angel and the Papal Tiara

The angel in the upper left is rendered with a luminous, almost sculptural presence. Partially emerging from a bank of clouds, the figure leans forward with one arm extended, hand open in a gesture that combines invitation and instruction. The angel’s wings create dark shapes that frame the head and torso, enhancing the dramatic effect.

Zurbaran carefully avoids turning the angel into a mere decorative element. The messenger’s gaze is directed firmly toward Bonaventure, implying an intimate conversation. The exact content of the message is left unspecified, which allows viewers to project various interpretations: a divine command to refuse the papacy, an affirmation of his Franciscan calling, or simply a reassurance that God sees his struggle.

On the table, the papal tiara stands as a tangible counterpoint to this heavenly guidance. It is painted with great attention to detail: multiple crowns rising in tiers, small crosses and jewels, all resting on a silver platter atop the red cloth. The platter emphasizes that the office is being offered, almost like a ceremonial gift presented at a banquet.

Yet the tiara is also somewhat isolated. No human hand touches it, and it seems slightly off to the side of Bonaventure’s kneeling form. This spatial separation suggests that, despite its proximity, it remains external to his true identity. The saint belongs to the Franciscan habit, not to the triple crown of papal power.

Cardinals, Onlookers and Architecture in the Background

To the right, behind the dividing wall, stands a cluster of cardinals in vivid scarlet robes. Their presence connects the scene to the institutional Church. Some appear engaged in conversation, others glance toward the kneeling figure, yet all remain physically distant. Their brilliant red garments echo the color of the tablecloth, visually linking the world of ecclesiastical politics with the tempting symbol on the table.

Below them, three men in darker clothing look on. These could represent theologians, clerics or lay supporters. Their expressions are more varied and harder to read, perhaps indicating curiosity about the outcome of the election or concern for Bonaventure’s decision.

The architectural background includes a large church or basilica, with classical elements and a dome. This setting places the event in the ecclesiastical heart of Christendom and suggests the weight of tradition and authority that surrounds Bonaventure’s potential elevation. Yet the distance and soft focus of the building reinforce that, for the moment, the true center of the story lies in the intimate space of prayer at the front.

Color Symbolism and Emotional Tone

The predominance of red and gray in the painting carries strong symbolic resonance. Red appears in the cardinals’ robes, the tablecloth and, faintly, in the sky. It suggests power, passion, and the blood of Christ that undergirds the Church. In contrast, Bonaventure’s habit is gray, a color of humility, withdrawal from worldly splendor and the simple life of a friar.

The juxtaposition of these two color zones reflects the tension in Bonaventure’s life. As a cardinal, he belonged to the hierarchy signified by red, yet his Franciscan heart remained anchored in the gray of poverty. Zurbaran’s palette makes this internal conflict visible.

The overall mood is solemn but not despairing. Warm light and soft transitions keep the scene from feeling harsh. The angel’s presence introduces an element of hope and reassurance. Even the reds, although intense, are tempered by shadows, suggesting that ecclesiastical power itself is not evil, only potentially overwhelming without divine guidance.

Zurbaran’s Style at the End of His Career

Painted around 1650, “St. Bonaventure” belongs to the later phase of Zurbaran’s career. By this time he had refined his approach to religious subjects, moving from the stark tenebrism of his early years toward a somewhat softer, more atmospheric handling of light. In this work, the shadows are deep but not absolute; forms remain legible even in darkness.

The figures show the sculptural solidity characteristic of Zurbaran. Bonaventure’s habit and the angel’s body have the weight and presence of carved stone, yet the painter’s touch lends them a gentle liveliness. The composition remains simple and uncluttered, focusing on a few key elements rather than distracting with ornamental detail.

Compared with other Spanish Baroque artists, Zurbaran stands out for his ability to convey intense spirituality through stillness rather than through swirling movement. “St. Bonaventure” is a perfect example. There is very little physical action, yet the viewer senses a profound inner decision taking place.

Spiritual Themes and Contemporary Relevance

The themes embedded in “St. Bonaventure” remain relevant far beyond its historical context. At its core, the painting explores the tension between ambition and vocation, between external honors and inner fidelity to God. Bonaventure is not tempted by something obviously sinful, but by an office that carries immense responsibility and potential for good. The question is not merely whether he will be powerful, but whether accepting such power aligns with his specific calling.

For modern viewers, this can resonate with experiences of career advancement, public recognition or leadership roles. The painting suggests that discernment requires stepping back from pressure and listening for a deeper voice. Like Bonaventure, individuals may need to kneel metaphorically before God, weighing opportunities not only in terms of prestige but in terms of faithfulness to their core identity.

The image also highlights the importance of humility in leadership. Bonaventure’s reluctance to grasp at power contrasts with many historical abuses of ecclesiastical authority. The painting offers a counter model: a leader who seeks guidance before accepting responsibility, and who is willing to decline honors if they threaten his spiritual integrity.

Finally, the presence of the angel reminds viewers that decisions of great importance are not made alone. Divine grace, represented by the bright messenger, accompanies and enlightens those who sincerely seek God’s will. This assurance can be consoling to anyone facing a difficult choice.

Conclusion

Francisco de Zurbaran’s “St. Bonaventure” is far more than a historical vignette of a medieval theologian. It is a profound visual meditation on prayer, humility and the discernment of vocation. Through a carefully balanced composition, expressive use of light and color, and the interplay between the papal tiara, the kneeling friar and the angelic messenger, Zurbaran invites viewers into the saint’s inner struggle.

The cardinal’s red robes and monumental church in the background testify to the weight of institutional expectation, while the solitary figure in gray reminds us that authentic holiness often takes shape in quiet, hidden decisions. The painting continues to speak across centuries, encouraging anyone who contemplates it to seek divine guidance amid the pressures of ambition and responsibility.

In the stillness of Bonaventure’s prayer and the luminous gesture of the angel, Zurbaran offers a timeless image of a heart choosing fidelity to God above all else.