Image source: wikiart.org

A Tender Vision of Sacrifice: Introducing Murillo’s “The Christ Child asleep on the Cross”

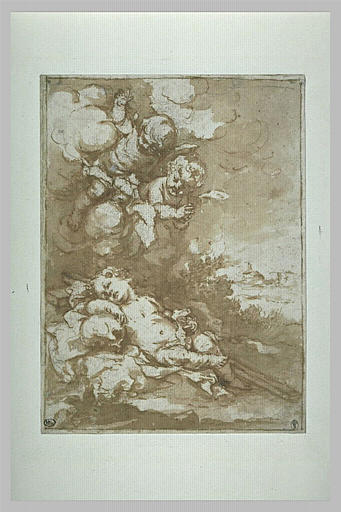

“The Christ Child asleep on the Cross” by Bartolome Esteban Murillo is a small but powerful devotional image created around 1670. At first glance it feels intimate and quiet. The entire composition is rendered in a warm monochrome wash, suggesting a preparatory drawing or a finished study rather than a large public altarpiece. Yet in this modest format Murillo brings together themes that shaped his whole career: childhood innocence, divine love, and the mystery of Christ’s sacrifice.

Murillo worked in Seville at the height of the Catholic Reformation. Artists were expected to inspire piety, to move the heart rather than merely impress the eye. This image answers that demand perfectly. By showing Jesus as a sleeping child resting on the symbol of his future death, Murillo compresses the whole story of the Gospel into a single tender moment. The viewer is invited to contemplate the paradox of a baby who is already a savior and a victim, cherished and vulnerable yet quietly accepting his destiny.

Even in this reduced, almost sketch like image, Murillo’s gift for emotional storytelling is clear. The clouds, the small angels, and the sleeping boy are all orchestrated to create a gentle yet haunting meditation on love, suffering, and trust in God.

First Impressions: Reading the Monochrome Composition

The image is vertically oriented, framed by a simple border that reinforces the sense of a cherished devotional sheet or design for a print. Inside this frame, Murillo builds the scene almost entirely out of tonal values rather than color. Brown ink or wash forms the figures, the clouds, and the distant landscape, while the surrounding paper becomes the source of light.

In the lower left, the Christ Child lies across the diagonal form of a wooden cross. His body is slightly twisted, suggesting both the natural rest of a sleeping child and a faint echo of the crucified pose he will one day assume. His head is relaxed, his face turned toward the viewer, and the softness of his features creates a sharp emotional contrast with the rough geometry of the cross itself.

Above and around him, a swirl of cherubic figures and clouds fills the sky. These little angels lean forward, their plump faces and tiny hands forming a protective canopy over the sleeping child. They emerge from the clouds, some more clearly defined, others barely suggested with a few strokes of wash. To the right, the forms dissolve into a luminous open space that may represent both a distant landscape and the infinite realm of heaven.

The monochrome treatment invites the viewer to focus on gesture and tone rather than decorative detail. Light seems to emanate from the Christ Child himself, while the surrounding forms are modeled in darker washes. The result is a quiet, contemplative atmosphere. Despite the drama of the subject, nothing feels violent. Instead the scene appears hushed, like a prayer whispered in the early morning.

The Sleeping Christ Child: Innocence on the Edge of Destiny

At the emotional core of the image lies the sleeping boy. Murillo was famous for his depictions of children, especially the street urchins of Seville, and he brings that same understanding of childhood to this holy subject. The Christ Child does not look like a miniaturized adult. He looks genuinely young. His cheeks are full, his limbs soft, his posture relaxed in the complete trust of deep sleep.

This innocence is crucial to the meaning of the work. Murillo asks the viewer to hold two ideas in mind at once. On one side we see an ordinary child, vulnerable and oblivious, the way any child appears when sleeping peacefully. On the other side we know that this child is Christ, whose life will culminate in the agony of the crucifixion. The cross is already under him, a foreign object in the world of childhood, yet he accepts it almost as if it were a pillow or a cradle.

The contrast between the softness of his body and the rigid diagonal of the cross intensifies the pathos. The child’s arm and leg drape naturally across the wood. His hand may touch or nearly touch the intersection of the beams, a subtle hint of the future placement of the nails. By letting the viewer see these small correspondences Murillo invites a meditative reading. The sleeping figure becomes a quiet prophecy of the Passion.

The eyes closed in sleep also suggest a spiritual dimension. Sleep can symbolize trust, abandonment to divine will, or even foreshadow death and resurrection. In this context the Christ Child’s slumber hints that his sacrifice, though terrible, is part of a divine plan that he accepts without resistance. The viewer is encouraged to imitate that trusting surrender.

The Cross as Cradle and Prophecy

The cross in this composition is more than a prop. It is the central sign that transforms a charming child study into a deeply theological image. Murillo positions the cross diagonally, cutting across the lower half of the picture. This diagonal gives the scene energy but also creates a sense of instability, as if the peaceful moment could end at any time. The child is secure for now, but the instrument of his death is already present.

At the same time the cross functions almost like a cradle or bed. The child’s body curves around it, and his head finds a resting place along its beam. In visual terms Murillo fuses two iconographic traditions. One is the Nativity and the tender images of the Virgin with the sleeping baby Jesus. The other is the Crucifixion and the long tradition of meditating on the instruments of the Passion. The cross in this image belongs fully to neither world yet touches both. It is at once a piece of rough wood and a foreshadowed altar of sacrifice.

This dual role of the cross would have resonated strongly with seventeenth century Spanish viewers steeped in Catholic spirituality. Devotional texts of the period often encouraged believers to contemplate the Passion not only as a historical event but as an ongoing reality present from Christ’s birth onward. Murillo’s visual strategy matches that theology. The child resting on the cross makes visible the idea that Christ came into the world precisely to redeem it through suffering.

Angels and Clouds: A Heavenly Witness

Murillo fills the upper part of the composition with swirling clouds and tiny angels. These cherubs act as both witnesses and guardians. They cluster around the central figure, some leaning in as if in conversation, others looking outward toward the viewer. Their presence turns an intimate domestic scene into a cosmic one. Heaven itself is already watching over the sleeping child and contemplating the mystery of his future sacrifice.

The angels also help guide the viewer’s eye. Their bodies form a loose spiral that begins near the child and rises into the upper left corner. This movement suggests uplift, drawing the viewer’s thoughts from the earthly realm toward the divine. Yet the cherubs are themselves very human in their expressions. Their rounded faces and playful poses recall the children in Murillo’s genre scenes. This blending of sacred and everyday qualities makes the spiritual message more accessible. The heavenly beings feel close and affectionate rather than distant and awe inspiring.

The clouds, rendered in soft washes of varying intensity, wrap around the figures like a curtain. They create depth without the need for a detailed architectural setting. This abstraction keeps the focus on the emotional relationships rather than on secondary details. The indistinct boundary between cloud and sky also suggests the idea that heaven is not a distant place but a reality that touches the earthly world wherever Christ is present.

Light, Shadow, and the Poetics of Sepia

Although the drawing lacks color, it is rich in tonal nuance. Murillo uses the white of the paper as his brightest light. The Christ Child’s skin is modeled with only a few gentle shadows, which makes his body appear luminous against the darker forms of the cross and the surrounding drapery. This contrast reinforces the spiritual symbolism of Christ as the light in the darkness.

The cross is rendered with denser wash and firmer strokes, underlining its physical weight and solidity. The deep shadows between the beams and under the child’s body build a sense of volume. Meanwhile the clouds and angels are painted with a range of mid tones that create a soft, vaporous atmosphere. Some areas are barely indicated, becoming almost abstract shapes of light and dark. This economical handling adds to the dreamlike quality of the scene.

The sepia palette itself contributes to the mood. Brown ink has a warmth that pure black lacks. It resembles aged parchment or the color of earth, linking the divine drama to the physical world. For a seventeenth century viewer the work might have appeared as a precious object, its warm tones inviting close, prolonged contemplation. The limited palette also allows subtle shifts in value to carry expressive weight. A slightly darker stroke around the child’s face or hand can guide the eye and emphasize key details.

Murillo’s Devotional Vision and the Culture of Seville

To fully appreciate this image it helps to consider the spiritual climate of Seville in Murillo’s time. The city was a major religious and commercial center of the Spanish empire. Its churches and confraternities commissioned paintings that aimed to stir the faithful to compassion, repentance, and love for Christ and the Virgin. Murillo became one of the most sought after painters for such works because he combined doctrinal clarity with emotional warmth.

Images of the Christ Child were especially popular in Spain, where devotion to the Niño Jesús took many forms. Sculptures and paintings showed the child blessing, playing, or appearing in visions to saints. Murillo’s treatment of the sleeping Christ on the cross fits into this broad tradition but adds a particular emphasis on meditation on the Passion. Rather than emphasizing royal triumph or playful charm, he centers the image on the quiet acceptance of suffering for the sake of humanity.

The drawing could have been intended as a model for a larger painting, a print, or even a small altarpiece. Whatever its final destination, the composition reflects the priorities of Catholic Reformation art: clarity of narrative, emotional appeal, and accessibility for all kinds of viewers. The theological content is present but not presented in a dry, intellectual way. Instead it is embodied in the simple, touching figure of a child at rest.

Childhood, Poverty, and Compassion in Murillo’s Art

Murillo often painted poor children, beggars, and street urchins he observed around Seville. These images, now admired for their charm, originally carried a strong moral and devotional message. They reminded wealthy viewers of the Christian duty to charity. In “The Christ Child asleep on the Cross” we can sense a similar current of tenderness and concern.

Although this is a divine child, his vulnerability mirrors that of the poor children Murillo saw every day. His body is unprotected, his clothing minimal, his bed a rough piece of wood rather than a soft cushion. The viewer is invited to feel compassion not only for Christ but for all children who suffer. In this way the image connects the supernatural drama of the Passion with the concrete reality of human hardship.

Murillo’s ability to evoke empathy through the depiction of children was one of his greatest strengths. He never idealizes them into cold symbols. Instead he captures tiny gestures of relaxation, the weight of a limb at rest, the turn of a head that feels completely natural. These details deliver the emotional impact of the work more powerfully than any theoretical explanation could.

A Personal Image for Private Devotion

The modest size and intimate character of this drawing suggest that it may have been meant for private use or as a design closely studied by the artist and his patrons. Unlike large altarpieces that address an entire congregation, this image speaks directly to a single viewer. It invites quiet contemplation rather than public ceremony.

In devotional practice such an image would serve as a focus for meditation. A believer might reflect on the trust of the sleeping child, compare it to their own anxieties, and be encouraged to place their worries in God’s hands. The juxtaposition of peace and impending suffering could also inspire gratitude and sorrow for Christ’s sacrifice.

Because the face of the Christ Child is turned slightly outward, the viewer feels almost included in the scene. It is as if we have approached quietly and found him sleeping, watched by the angels. The cross under him tells us that this peaceful moment is fragile, and that our own salvation depends on what he will one day endure. The effect is both humbling and consoling.

Continuing Impact and Modern Reflection

Although created for a seventeenth century Catholic audience, “The Christ Child asleep on the Cross” still speaks to viewers today. Even for those who do not share the original religious beliefs, the image offers a meditation on vulnerability, destiny, and the cost of love. Parents recognize the instinct to protect a sleeping child at all costs. The presence of the cross in this context raises universal questions about sacrifice and the ways people accept suffering for those they love.

From an art historical perspective, the work showcases Murillo’s mastery of line and tone in drawing. It reveals his process of building a composition from simple shapes, setting emotional emphases through light and posture, and integrating figures into a dynamic yet harmonious whole. The drawing reminds us that even grand religious narratives begin with subtle decisions on a sheet of paper.

For viewers exploring Murillo’s oeuvre, this image offers an important key to his larger paintings. The combination of warmth, compassion, and theological depth seen here runs through his famous works of the Immaculate Conception, the Holy Family, and scenes of charity. “The Christ Child asleep on the Cross” distills those themes into a single, unforgettable vision that lingers in the mind long after one has looked away.