Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Angel with the instruments of whipping

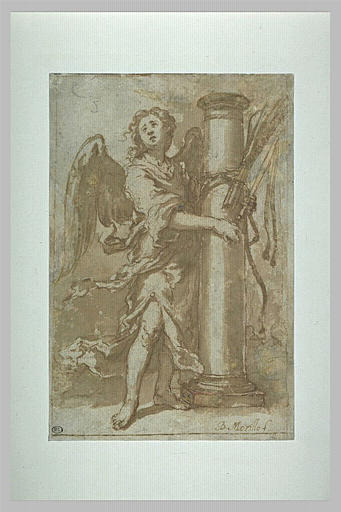

“Angel with the instruments of whipping,” created around 1660 by Bartolome Esteban Murillo, is a small yet remarkably expressive drawing that belongs to the artist’s series of angels bearing the Instruments of the Passion. Executed in brown ink and wash, the work shows a graceful angel standing beside a tall column and presenting the scourges used in the flagellation of Christ.

At first glance the image appears simple, almost understated. There is no crowd, no blood, no graphic depiction of suffering. Instead, Murillo chooses a quiet moment of contemplation. The angel’s body curves around the column, one foot stepping forward, robe swirling in soft folds, wings half open as if caught in a gentle breeze. In its hands are the whips that once tore Christ’s flesh. Between the peaceful bearing of the messenger and the violent purpose of the objects it holds, a powerful tension emerges. This tension is at the heart of the drawing and of the devotion it invites.

The Passion Tradition and Murillo’s Spiritual World

To understand the meaning of this drawing, it helps to recall the culture of seventeenth century Seville. The city was famous for its Holy Week processions and for its intense meditation on the Passion of Christ. Confraternities commissioned sculptures and paintings that represented different moments of the Passion, encouraging believers to follow Christ step by step from the Last Supper to the Crucifixion.

Murillo, one of Seville’s leading painters, responded to this devotional atmosphere with numerous works that present Christ, the Virgin and angels in gentle, approachable ways. Instead of emphasizing horror, he often highlights compassion and consolation. His series of Passion angels to which this drawing belongs fits perfectly into that spiritual context. Each angel carries a different instrument of suffering, not as an executioner but as a reverent guardian of sacred memory.

The scourging at the column is one of the most painful episodes in the Passion narrative. Christ, bound to a pillar, is whipped by soldiers until his body is covered with wounds. In Murillo’s drawing nothing of this violence is shown. Only the column remains, now a silent monument, while an angel holds the whips with a mixture of sorrow and tender respect. The scene shifts from physical cruelty to spiritual remembrance.

Composition and the Dance around the Column

The composition is ingeniously simple. A tall stone column stands slightly right of center, rising almost to the top of the sheet. Its vertical solidity anchors the drawing and immediately recalls the scene of Christ’s flagellation. Around this unyielding pillar the angel moves in a flowing arc.

Murillo positions the angel so that one arm reaches behind the column while the other rests along its side. The torso twists gently, the head turning back over the shoulder as if the messenger had been walking past and suddenly paused in recognition. The left leg steps forward, bare foot firmly planted, while the other leg bends behind. This contrapposto stance gives the figure a sense of motion and life.

The wings frame the figure, one sweeping behind the column, the other stretching outward on the left. Their curved forms soften the rigid geometry of the pillar and echo the swirling lines of the robe. The drapery itself is full of lively folds that catch the light and create a rhythmic pattern across the figure. Together, wings and drapery create a visual dance around the column, suggesting that grace surrounds even the instruments of torture.

The scourges, with their cords and knots, hang from the angel’s right hand and from a hook near the top of the pillar. They trail down in looping lines that contrast with the vertical shaft of the column. Although small in scale, they are clearly drawn, ensuring that the viewer recognizes them as the tools of whipping.

The Angel’s Gesture and Expression

Central to the emotional impact of the drawing is the angel’s gesture. The figure’s head tilts slightly upward, eyes lifted toward an unseen source of light. The mouth is parted, suggesting breath or speech, as if the angel were silently praying or listening. There is no smile and no dramatic grief, only an attentive, almost wondering expression.

One hand encircles the column low down, palm pressed against the stone. This touch feels protective and reverent, as if the angel is embracing the memory of Christ’s suffering rather than recoiling from it. The other hand holds the bundle of scourges. The grip is firm yet gentle, conveying both the seriousness of what these objects represent and the care with which heaven now handles them.

The bare feet and the movement of the robe reinforce the sense that the angel is both grounded and in motion. This is a traveler in the spiritual landscape of the Passion, pausing at the site of the flagellation. The posture invites the viewer to pause as well, to circle mentally around the column and to ponder the love that endured such pain.

Symbolism of the Column

The column is more than a piece of architecture. In Christian art it is a well established symbol of Christ’s endurance during the flagellation. Bound to the pillar, Christ became like a living column himself, steadfast in obedience to the Father. In some mystical writings the column is compared to the upright tree of the Cross, a precursor to the final instrument of death.

Murillo renders the column with simple clarity. It rests on a circular base and is topped by a rounded capital. There are no decorative carvings, no ornate details, just smooth stone rising from the ground. This plainness emphasizes its symbolic function. The pillar stands as a witness to an event that has already taken place, a silent monument that remembers without words.

The way the angel wraps an arm around the column suggests that this monument is not cold and distant. It is something to which a loving being can cling. The column becomes a meeting point between heaven and earth, a place where divine compassion and human cruelty once intersected and where, in memory, they still meet.

Symbolism of the Instruments of Whipping

The scourges or whips that the angel holds are among the most evocative of the Instruments of the Passion. They consist of cords, often with knots or bits of metal attached, designed to tear the skin. In devotional art they remind believers of the physical reality of Christ’s suffering.

In Murillo’s drawing these tools appear small and almost fragile, yet their significance is immense. Their placement high on the column and in the angel’s hand elevates them from base weapons to relics. They are no longer in the hands of cruel soldiers, but in those of a messenger from heaven. This change in ownership transforms their meaning. They become signs of a love that accepted humiliation and pain for the sake of humanity.

The cords of the scourges create a tangle of lines that contrasts with the broader planes of the column and the robe. This visual contrast may suggest the chaos and confusion of violent human actions against the clarity and solidity of Christ’s purpose. The angel, who holds the cords carefully, acts as a mediator who renders that chaos contemplative, making it possible for the viewer to look upon these instruments without horror.

Technique, Medium and the Power of Monochrome

Like many of Murillo’s passion related drawings, “Angel with the instruments of whipping” is executed in brown ink and wash. This limited palette creates a warm monochrome that resembles aged parchment. The absence of bright color turns attention to line, form and light.

Murillo first defines the contours of the figure and column with fine pen strokes. Then he adds washes of diluted ink to model volume and suggest shadow. Darker tones appear under the folds of the robe, along the shaded side of the column and beneath the angel’s feet. Highlights are left as untouched paper, especially on the face, the front of the column and the edges of the wings.

This interplay of light and dark gives the drawing a sculptural quality. The angel seems to emerge from the page as if carved from warm stone or illuminated by candlelight. The soft transitions between tones create a meditative atmosphere well suited to the subject. The viewer is invited to move slowly across the image, discovering subtle details in the folds and feathers.

The small size of the drawing encourages intimate viewing. Held close, it becomes a personal object of devotion rather than a public spectacle. This intimacy reflects Murillo’s sensitivity to the private prayer life of his patrons and contemporaries.

Emotional Tone and Contemplative Invitation

Despite its association with one of the harshest episodes of the Passion, the drawing is remarkably calm. There is no blood, no depiction of Christ’s suffering body, no aggressive movement. Instead, a quiet angel stands guard over the memory. This calm does not minimize the seriousness of the event. Rather, it presents it as something already embraced and transformed by divine love.

The angel’s upward gaze encourages the viewer to look beyond the instruments of pain toward their spiritual meaning. The composition leads the eye from the bare feet on the ground up along the twisting body, around the column and finally to the face turned heavenward. The movement becomes a visual allegory of spiritual ascent. One begins with the harsh reality of suffering, passes through remembrance and arrives at contemplation of God’s mysterious plan.

For believers, looking at this drawing could support a form of prayer that slowly considers each instrument of the Passion and the love it represents. The column and whips become prompts for gratitude rather than fear. The presence of the angel assures that one is not alone in this meditation. Heaven itself remembers with us.

Place within Murillo’s Series of Passion Angels

“Angel with the instruments of whipping” is part of a broader group of drawings in which Murillo depicts angels carrying different objects connected with Christ’s suffering. Other sheets show an angel with the cross, with nails and hammer, with the lantern and sword from Gethsemane, or with the crown of thorns. Each figure is shown alone with its particular attribute, moving through an undefined space of clouds and light.

Considered together, these drawings form a visual litany of the Passion. Each angel embodies a specific moment or instrument, and together they guide the viewer through the story of Christ’s final hours. The angel with the whips occupies the stage between the arrest in the garden and the crowning with thorns, focusing attention on the scourging that prepared the way for the Crucifixion.

Murillo’s consistent approach across the series emphasizes continuity. The angels share a similar elegance of pose and a common emotional mood of gentle gravity. Yet each one has its own character defined by the object it carries. The angel of the whips, wrapped protectively around the column, may be seen as a symbol of steadfast endurance and compassionate remembrance.

Murillo’s Artistic Personality Reflected in the Drawing

Murillo is celebrated for his ability to infuse religious themes with warmth and humanity. In his large canvases of the Immaculate Conception and the Holy Family, he often bathes figures in soft light and surrounds them with playful cherubs. Even in scenes that might invite harsh realism, he chooses a tone of mercy and tenderness.

This drawing reflects the same personality in a distilled form. Murillo does not ignore the reality of suffering. The scourges are clearly there, the column firmly rooted. Yet the overall feeling is one of hope. The angel’s presence suggests that suffering has been taken up into the sphere of grace. The lines are fluid rather than harsh, the shadows soft rather than brutal.

In this way Murillo offers a vision of the Passion that comforts as it challenges. The viewer is invited to acknowledge the depth of Christ’s pain, but also to trust in the transformative power of divine love. The drawing becomes a quiet teacher of patience, empathy and trust.

Conclusion

“Angel with the instruments of whipping” by Bartolome Esteban Murillo is a small masterpiece of Baroque devotion. Through a single figure, a plain column and a few carefully drawn whips, the artist evokes the entire drama of Christ’s scourging and its spiritual significance. The angel’s dynamic pose, tender gesture and upward gaze communicate both reverence and hope.

The column stands as a steadfast witness to suffering. The scourges, once symbols of cruelty, become relics held gently by heavenly hands. Murillo’s delicate use of brown ink and wash, his rhythmic drapery and his subtle play of light and shadow create an atmosphere in which the viewer can meditate calmly on serious themes.

More than three centuries after its creation, the drawing continues to speak to those who encounter it. It invites us to stand with the angel beside the column, to touch with our imagination the instruments of whipping and to look beyond them toward the love that transformed them. In this intimate image, Murillo turns the harshness of the Passion into an enduring source of contemplation and quiet consolation.