Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Saint Mary Magdalene” by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

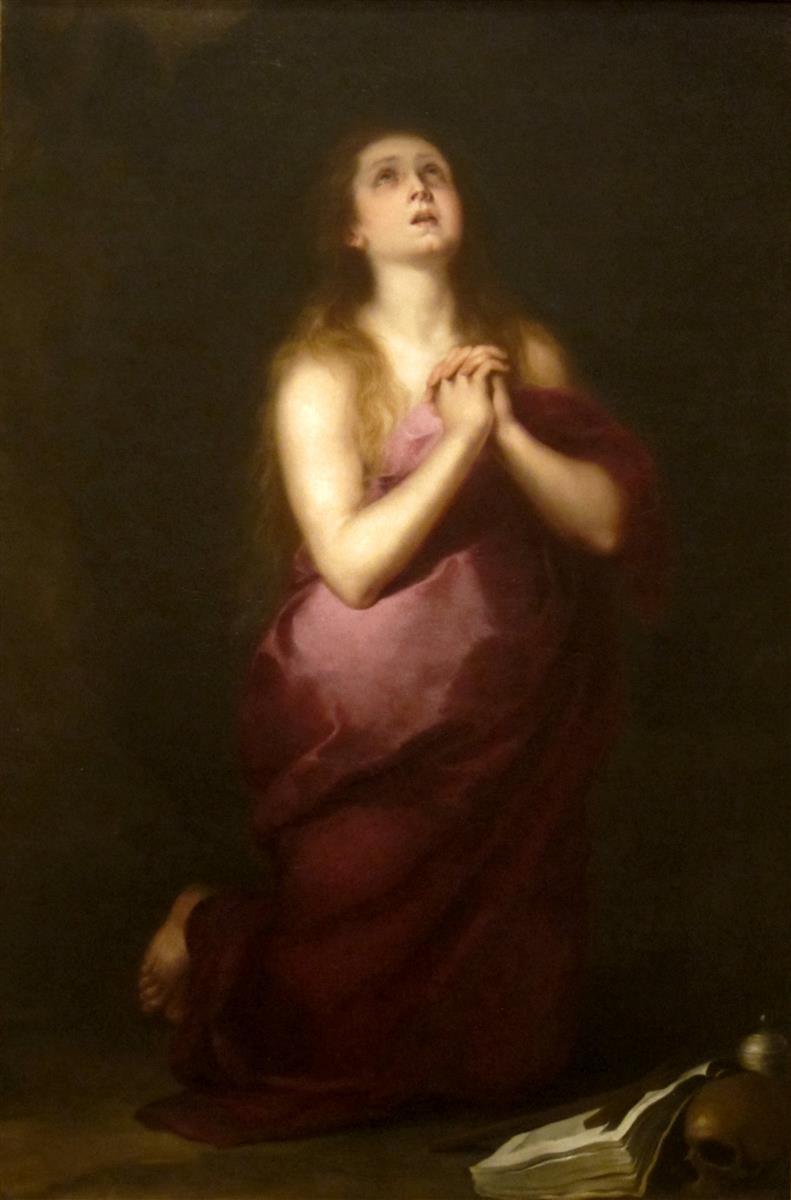

“Saint Mary Magdalene,” painted around 1655 by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, is one of the most touching images of penitence in Spanish Baroque art. The painting shows the saint kneeling alone in a dark space, wrapped in a rich reddish purple drapery that covers her body yet leaves her arms and shoulders bare. Her hands are clasped tightly at her chest, her head is tilted upward, and her eyes are lifted toward an unseen light above.

Near the lower right corner lie a skull, a book, and a small jar, traditional attributes of Mary Magdalene that point to themes of repentance, contemplation, and devotion. In this work Murillo abandons crowded narrative scenes in favor of a single, monumental figure isolated against darkness. The result is intensely introspective. The viewer feels invited into a private moment of prayer where sorrow, love, and hope meet.

Mary Magdalene as Penitent and Contemplative

Mary Magdalene holds a complex place in Christian tradition. For centuries she was understood as a woman who had lived a sinful life, often conflated with the anonymous sinner who anointed Christ’s feet with her tears. After encountering Jesus she repented and became one of his most devoted followers. In art she appears in several roles, but one of the most enduring is that of the penitent hermit, withdrawn from the world and given entirely to prayer.

Murillo chooses to show the Magdalene in this contemplative phase. There is no crowd around her, no landscape, no dramatic narrative. She is alone in a shadowy space, turned entirely toward God. The absence of other figures emphasizes the intimacy of her dialogue with the divine. Her lifted gaze and parted lips suggest that she is in the act of speaking or silently pleading.

By focusing on this solitary, upward looking pose, Murillo highlights the spiritual transformation of the saint. Whatever her past may have been, what matters now is the intensity of her love and her desire for forgiveness. The painting becomes a visual hymn to the possibility of renewal.

Composition and the Power of a Single Figure

The composition is remarkably simple yet carefully calculated. Mary Magdalene occupies the central vertical axis of the painting. She kneels on the ground, one foot visible and the other tucked beneath her, while the voluminous drapery of her garment pools around her legs. Her torso rises from this base in a gentle spiral, leading the eye upward from her clasped hands to her uplifted face and finally to the invisible source of light above the frame.

Murillo places the saint slightly to the left, leaving a broad expanse of dark space behind and above her. This emptiness is not accidental. It creates a sense of spiritual vastness, the unseen presence of God before whom she kneels. The empty darkness also heightens the figure’s isolation. There is nothing to distract or comfort her but the light that touches her skin.

At the lower right, the still life of book, skull, and jar forms a quiet counterweight to the figure. These objects are small compared with the saint, yet they are important anchors in the composition. Their diagonals and lines echo the tilt of her body, so that the whole canvas is bound together in a subtle rhythm.

Light, Shadow, and Spiritual Drama

The use of light in “Saint Mary Magdalene” is essential to its emotional impact. The background is almost entirely dark, yet a soft, golden illumination falls from the upper left, bathing the saint’s face, shoulders, and hands. This light is not harsh or theatrical. It has a gentle, enveloping quality, almost like the touch of grace.

The play of light across her skin and drapery creates a delicate contrast between the material and the spiritual. Her bare arms and shoulders are rendered with tender naturalism, emphasizing her humanity and vulnerability. At the same time, the luminous aura around her head and upper body suggests spiritual elevation. She appears to be both of this world and already partly beyond it.

The lower area of the painting is more subdued. The book and skull are half in shadow, indicating that they belong to the realm of earth and mortality. The jar catches a faint glint of light, enough to reveal its shape but not enough to steal attention from the saint’s face. Murillo’s control of values brings every element into a hierarchy, with the intensity of the saint’s prayer as the unquestioned focal point.

Color and the Drapery of Repentance

Color plays a subtle yet significant role in this painting. Mary Magdalene is wrapped in a flowing garment of deep reddish purple, a color associated both with passion and with sorrow. The hue suggests the intensity of her former life and the fervor of her present penitence. Within the folds of the fabric Murillo introduces variations of crimson, rose, and almost black, creating a rich visual texture that adds weight and presence to the figure.

Underneath the main garment hints of a lighter, pinkish fabric are visible, especially near her clasped hands. This soft inner color can be read as a symbol of the renewed heart, gentler and purified, hidden within the heavier cloak of penitence.

The rest of the color scheme is restrained. The background is composed of deep browns and muted earth tones. The skull, book, and jar are rendered in subdued hues that reinforce their associations with mortality, study, and anointing. Against this quiet palette the luminous flesh tones of the saint stand out. Her skin appears almost translucent, animated by a warm, internal glow that hints at the life of grace within her.

Facial Expression and Gesture

Murillo’s skill at capturing nuanced emotion is evident in Mary Magdalene’s expression. Her eyes are lifted and slightly moist, her mouth parted as if in whispered prayer. The muscles of her neck and the tilt of her chin convey both strain and yearning. She looks not only upward but beyond, to a presence that the viewer cannot see.

Her hands are clasped tightly at her chest, fingers interlaced in a gesture of urgent supplication. The tension in this gesture contrasts with the softness of her features. It is as though her whole body is gathered into a single movement toward God. Murillo allows a subtle tremor of vulnerability to show in the way her fingers press together and in the slight arch of her shoulders.

The overall effect is not theatrical despair but deep, interior emotion. The viewer senses that this is not the beginning of her repentance but a moment of long continued prayer, a point at which sorrow, love, and hope are fused. It is precisely this emotional complexity that gives the painting such enduring power.

Symbols at the Saint’s Feet

The objects placed near Mary Magdalene’s knees are traditional attributes that enrich the painting with layers of meaning.

The skull is a classic symbol of mortality. It reminds both the saint and the viewer that life is fleeting and that worldly pleasures end in death. In the context of Magdalene’s story, it refers to her renunciation of former vanities. She contemplates death not to fall into despair but to detach herself from what does not last and to seek what is eternal.

The open book suggests meditation on scripture or devotional texts. It indicates that Magdalene’s repentance is not pure emotion but also thoughtful contemplation. She seeks knowledge of God’s will and guidance for her renewed life. The pages catch some light, hinting that the word she reads is itself a source of illumination.

The small jar recalls the ointment with which she anointed Christ’s feet. It serves as a memory of the moment when she expressed her love through a lavish gesture, breaking the jar and pouring its contents as a sign of total self giving. In this painting the sealed jar becomes a quiet reminder of that earlier episode and of the connection between love and sacrifice.

Together, skull, book, and jar tell a story of transformation. Death, knowledge, and devoted action shape the path of the penitent saint. Murillo integrates these symbols discreetly, so that they support rather than dominate the main image.

Murillo’s Magdalene and Spanish Baroque Spirituality

Murillo painted several versions of Mary Magdalene, and they all share an atmosphere of gentle introspection. In contrast with more dramatic Baroque depictions that show the saint in wild ecstasy or physical mortification, Murillo favors a restrained, contemplative mood. His Magdalene is deeply emotional but never hysterical. She embodies the ideals of Spanish Counter Reformation spirituality, which valued heartfelt contrition, interior prayer, and trust in divine mercy.

The Spanish mystics of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, such as Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross, wrote about experiences of darkness and light, absence and presence, that resonate with the visual language of this painting. The dark void behind the saint can be read as the spiritual night through which the soul must pass. The soft light that falls on her face suggests the consoling presence of God, often felt more than seen.

Murillo’s emphasis on the beauty and vulnerability of the human body also reflects a Catholic sacramental worldview, in which the material world is seen as capable of revealing spiritual realities. Mary Magdalene’s bare arms and flowing hair are not merely sensual details. They testify to the goodness of the human person, even when wounded by sin. Her very physicality becomes the site of redemption.

Artistic Style and Murillo’s Signature Softness

In “Saint Mary Magdalene” Murillo displays many features of his mature style. His handling of paint is smooth and blended, especially in the transitions of light across skin and fabric. This softness gives the figure a dreamlike quality, as if she exists in a space between the earthly and the heavenly.

At the same time, the anatomical structure is solid. The way her weight rests on one knee, the curve of her spine, and the positioning of her arms all feel natural and believable. Murillo combines idealization with realism in a way that invites both aesthetic admiration and emotional identification.

The painting also shows his gift for integrating figure and background. The dark setting is not a mere backdrop, but a kind of atmosphere that envelops the saint. The edges of the drapery dissolve gently into shadow, creating a sense that she is emerging from or receding into a mysterious depth. This atmospheric unity is a hallmark of Murillo’s most successful works.

Devotional Impact and Modern Reception

For its original viewers, this painting would have functioned as an aid to devotion. Contemplating Mary Magdalene’s intense prayer, they were encouraged to examine their own hearts, to acknowledge sin, and to trust in God’s mercy. The saint serves as a mirror and a model. She reflects human frailty, yet she also shows the possibility of radical change.

Today, even outside explicitly religious contexts, the painting continues to move viewers. Many respond to the honesty of the emotion, the sense of a person laid bare before something greater than herself. The image speaks to universal themes of regret, longing for forgiveness, and the desire for a new start.

In a world that often prizes self assurance and public success, Murillo’s kneeling Magdalene reminds us of the power of vulnerability and the courage involved in admitting need. Her upturned face and clasped hands express a hope that transcends specific doctrines. Through this combination of personal feeling and spiritual symbolism, the painting retains a compelling relevance.

Conclusion

“Saint Mary Magdalene,” created by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo around 1655, is a masterpiece of Baroque religious painting and a deeply human portrayal of penitence. With a single kneeling figure, a handful of symbolic objects, and a dramatic yet gentle play of light and shadow, Murillo invites the viewer into a quiet but intense moment of prayer.

The saint’s uplifted gaze, tightly clasped hands, and flowing garment of reddish purple convey a powerful mixture of sorrow, love, and hope. The dark background emphasizes her isolation while suggesting the vastness of the divine mystery that surrounds her. The skull, book, and jar at her feet enrich the image with reflections on mortality, contemplation, and devoted action.

Murillo’s soft handling of paint, his sensitivity to emotional nuance, and his integration of spiritual symbolism make this painting an enduring reflection on the possibility of transformation. “Saint Mary Magdalene” stands as a visual reminder that even from the depths of remorse, a soul can rise toward light, sustained by the belief that mercy is greater than any past.