Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Head of a Young Man” by Peter Paul Rubens

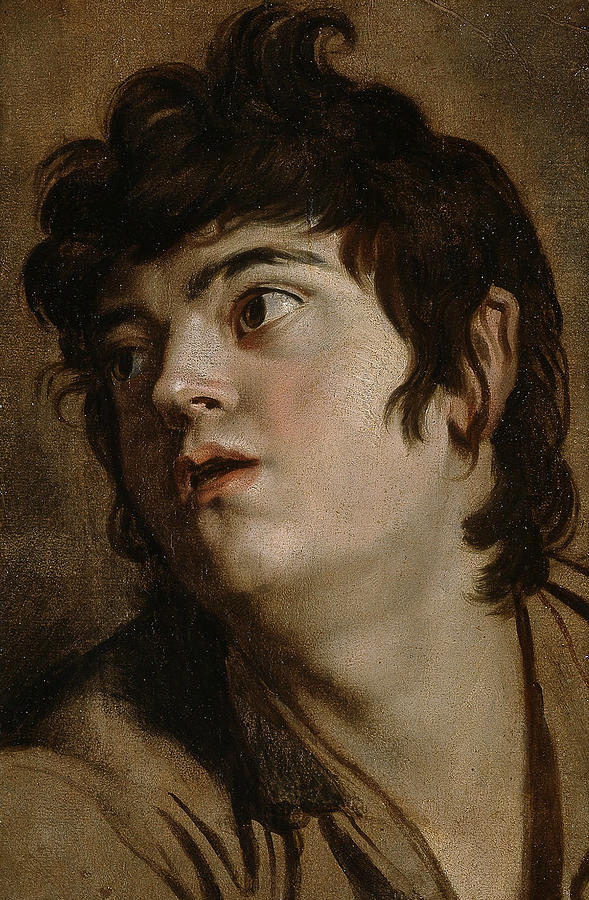

“Head of a Young Man” by Peter Paul Rubens is a compact but powerful exploration of human emotion. Unlike his large mythological canvases filled with action and dramatic light, this painting focuses on a single face. The young man’s head is turned sharply to the side, his lips parted, his eyes wide and searching. There is a sense of surprise, even alarm, as if he has just seen something unexpected outside the frame.

The composition is simple but intense. The figure fills almost the entire surface, leaving very little background. This closeness creates an intimate encounter between viewer and subject. Rubens invites us into the inner life of this young man, offering a moment of psychological immediacy that feels almost modern. The painting may have served as a study for a larger work, yet it stands on its own as a complete and compelling image.

In this work Rubens shows how much drama can reside in a single human expression. Without props, elaborate costumes, or narrative setting, he conveys movement, emotion, and character using only the tilt of the head, the direction of the gaze, and the subtle modeling of flesh. “Head of a Young Man” reveals the artist’s deep understanding of how faces communicate feeling and how a carefully observed portrait can capture the vibrancy of human life.

Composition and Point of View

The composition is dominated by the young man’s head and upper shoulders. Rubens crops the figure very tightly, so that the chin nearly touches the bottom edge while the hair brushes the top. No hands are visible, no architectural elements appear, and the background is only a neutral, textured field. This tight framing focuses attention on the face and accentuates the dynamic tilt of the head.

The young man does not look directly at the viewer. His gaze is directed up and to the side, suggesting that something or someone off canvas has suddenly seized his attention. The neck twists slightly, and the shoulders turn in the opposite direction. This twist gives the composition a spiraling energy. The viewer senses movement, as if the sitter has just turned and is about to move again.

This point of view creates a sense of narrative without specifying a story. We do not know what he sees, but we feel the urgency of his response. The openness of the composition invites the viewer to imagine different scenarios. He could be a witness to a dramatic event, a figure in a religious scene, or simply a youth reacting to a voice in a crowded room. Rubens thus uses composition to open the portrait beyond mere likeness and into the realm of suggestion and drama.

Light, Shadow, and Color

Light plays a crucial role in shaping the emotional atmosphere of the painting. A soft illumination falls from the upper left, bathing the young man’s forehead, cheek, and nose. This light models the planes of the face, emphasizing the rounded cheekbones, the bridge of the nose, and the curve of the lips. It also creates highlights in the eyes, which sparkle with reflected light and help convey alertness.

Shadow takes on equal importance. The right side of the face, particularly near the jaw and ear, sinks into deeper tones. The hair becomes a dark mass broken by a few glints of light along individual strands. These contrasts of light and dark not only give the head volume but also contribute to the painting’s psychological depth. The alternation of illuminated and shadowed areas suggests inner tension, as if conflicting feelings are playing across the young man’s mind.

Rubens uses a restrained palette. Flesh tones range from warm pinks on the cheeks and lips to more neutral, slightly grayish hues on the neck and forehead. The background is a muted brown that recedes and allows the head to stand out. The clothing, glimpsed at the lower edge, is painted in earthy colors that do not distract from the face. This limited color range helps concentrate all visual interest on the expression and the play of light on skin.

The Expressive Power of the Face

What makes “Head of a Young Man” so compelling is the intensity of the expression. The mouth is slightly open, as if the figure has just spoken or is about to utter an exclamation. The parted lips hint at breathing, speech, or a sudden intake of air. This tiny detail helps give the painting a sense of life and immediacy.

The eyes are equally important. They are wide and directed upward, with visible whites that convey a heightened emotional state. This is not a calm, contemplative gaze. It is alert, reactive, and full of surprise. The raised eyebrows contribute to this impression, drawing the skin upward and creating subtle lines on the forehead.

The angle of the head reinforces the emotional effect. The young man does not simply turn his eyes. His whole head swings toward the source of interest. This full bodily engagement suggests that whatever he sees or hears has strong significance. Rubens thus captures a moment of psychological intensity, a fleeting instant when an emotion first appears on the surface of the face.

Hair, Clothing, and the Sense of Character

Although the painting focuses on the head, Rubens includes enough detail in the hair and clothing to suggest a specific type of character. The hair is thick, tousled, and slightly unruly, with locks curling upward. This roughness contributes to the sense of vigor and youth. It indicates a person who is active rather than formally posed, perhaps a figure caught in the midst of work or movement.

The clothing is simple and loosely rendered but appears to be that of an ordinary young man rather than a noble or courtier. The collar is plain, and the fabric falls in soft folds without ornament. These details hint that the sitter might be a model drawn from everyday life, an assistant, an apprentice, or a character study meant to be used in a narrative painting. Rubens was known to maintain a busy studio, and such studies provided him with a repertoire of faces that he could adapt to mythological or religious compositions.

Despite the modest clothing, the young man does not appear insignificant. His features are strong, his gaze intense, and his presence commanding. Rubens dignifies an ordinary face by presenting it with the same seriousness he would reserve for a historical or biblical figure. In this way, the painting bridges the gap between portrait and character study and affirms the intrinsic interest of the human face.

Brushwork and Painterly Technique

A closer look at the surface reveals Rubens’s lively brushwork. The paint is applied with varying degrees of thickness. In some places, particularly the highlights of the forehead and nose, the stroke is more loaded, giving a slight texture that catches the light. In other areas, such as the shadowed cheek and neck, the paint is thinner and more blended, creating smooth transitions between tones.

The hair is painted more loosely, with quick, curving strokes that describe individual locks without freezing them in place. This looseness contrasts with the more refined handling of the facial features and intensifies the impression of movement. The clothing, rendered in broader strokes, recedes into a softer focus. Rubens seems less concerned with precise detail here and more interested in building a base that supports the head.

This variation in brushwork gives the painting a living quality. The viewer’s eye experiences areas of sharp clarity and areas of soft suggestion, much like natural vision. The technique also hints at the painting’s function as a study. Rubens was likely working quickly, concentrating his attention on the features and expression while allowing the surrounding parts to remain more impressionistic. Yet the result feels complete, because the vitality of the brushwork matches the energy of the subject.

Possible Function as a Study or Character Head

Art historians often interpret works like “Head of a Young Man” as studies for larger paintings. Rubens frequently created separate oil sketches of heads that he would later incorporate into complex compositions. These character heads allowed him to experiment with lighting, expression, and perspective before committing them to a final canvas.

In that context, the heightened expression of this young man makes sense. He could have been intended as a witness to a miracle, a fleeing figure in a martyrdom scene, or an astonished onlooker in a dramatic narrative. The upward gaze might fit into a religious context, where the figure looks toward a divine apparition or a central event occurring above his line of sight.

Even if the painting originally served as a preparatory study, it stands today as an autonomous artwork. Its power does not depend on knowing which larger composition it might have belonged to. Instead, we can see it as a concentrated exercise in capturing an emotional reaction. This focus on the expressive head is highly characteristic of Baroque art, which sought to move the viewer not only through grand stories but also through the intensity of individual human responses.

Relationship to Baroque Portraiture and Rubens’s Style

“Head of a Young Man” exemplifies key aspects of Baroque portraiture. Rather than presenting the sitter in a static, frontal pose, Rubens captures a moment of action. The turning head, the animated expression, and the dramatic lighting all align with the Baroque interest in movement and emotion. Portraits of this period often aimed to show the sitter as a living person rather than a rigid emblem of status.

Rubens’s style is clearly visible in the soft transitions between light and shadow, the warm flesh tones, and the emphasis on physical vitality. His figures usually possess a sense of fullness and energy, even when they are still. In this painting, the young man’s cheeks and neck show that characteristic Rubensian solidity. He appears healthy, vigorous, and ready to act.

At the same time, the painting hints at Rubens’s admiration for Italian masters. The subtle modeling of the face, the use of warm brown grounds, and the tonal unity recall aspects of Venetian painting, particularly the work of Titian. Rubens studied in Italy early in his career, and that experience left a lasting mark. In “Head of a Young Man” he fuses this Italian influence with his own northern attention to texture and close observation.

Emotional Resonance and Modern Appeal

For contemporary viewers, “Head of a Young Man” feels surprisingly immediate. The youth’s expression, caught between fear, wonder, and alertness, is one that we can easily recognize from real life. This universality allows the painting to transcend its historical context. Even without knowing anything about the seventeenth century, a viewer can respond to the psychological tension on the canvas.

The closeness of the composition adds to this impact. We are drawn into the young man’s space, sharing his vantage point if not his exact experience. His parted lips and wide eyes suggest words about to be spoken or a cry about to escape. The painting arrests that moment before it unfolds, leaving us with a sense of suspended time.

This emotional resonance may explain why such studies, once considered secondary to grand historical canvases, are now highly prized. They reveal the artist’s hand at work and place viewers face to face with the human subjects of the past. “Head of a Young Man” invites not only admiration for Rubens’s skill but also empathy for the figure depicted. He is both an artistic creation and a believable young person whose sudden reaction continues to speak across centuries.

Conclusion

“Head of a Young Man” by Peter Paul Rubens is a masterful demonstration of how a single face can convey drama, movement, and inner life. Through tight composition, sensitive use of light and shadow, and expressive brushwork, Rubens transforms what might seem a simple study into a compelling portrait of emotion. The young man’s upward gaze and parted lips capture a fleeting instant of intense response, leaving the viewer to imagine the unseen event that provokes it.

The painting showcases Rubens’s ability to model flesh with warmth and subtlety, to animate hair and fabric with lively strokes, and to create psychological depth without relying on elaborate narrative devices. It bridges the worlds of preparatory sketch and finished portrait, offering insight into the artist’s working process while standing as a complete artwork in its own right.

For modern audiences, “Head of a Young Man” remains striking in its immediacy. The emotional truth of the expression, the intimacy of the viewpoint, and the vitality of the painted surface combine to make this small work a powerful encounter with Baroque art. In the direct, searching gaze that never quite meets ours, we glimpse not only the skill of Rubens but also the enduring fascination of the human face as a mirror of inner experience.