Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Christ Attended by Angels Holding Chalices

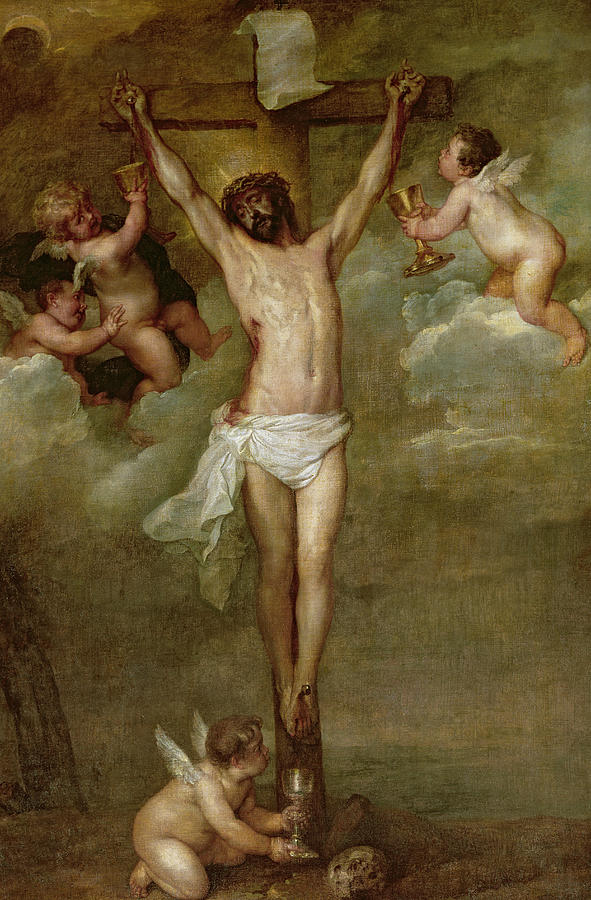

“Christ Attended by Angels Holding Chalices” by Peter Paul Rubens presents the Crucifixion in a register at once intimate and cosmic. The body of Christ hangs on the cross at the center of the composition, his head inclined, his torso illuminated against a soft, vaporous sky. Around him cluster small winged angels who hover on clouds and kneel at the base, each bearing a golden chalice. They catch and present the streaming blood from his hands, feet, and side, transforming the scene of execution into a liturgy of redemption. Rubens’s image belongs to the Baroque current of devout painting that sought to make doctrine sensuously visible: here, the suffering of the Savior becomes inseparable from the mystery of the Eucharist, with angels functioning as acolytes in an eternal Mass.

Composition and the Centering of the Crucified

Rubens sets the cross upright and monumental, yet he resists theatrical diagonals or tumultuous crowds. The figure of Christ forms a perfect vertical, from the outstretched hands down the length of his body to the single foot resting on the small suppedaneum. The slight twist of the torso, the turn of the head toward the right shoulder, and the knot of the white loincloth create a subtle S-curve that lends grace to the agony. This classical poise, learned from the antique and the High Renaissance, intensifies rather than diminishes pathos; the beauty of the body serves as a vessel for sacrificial meaning.

The surrounding angels construct a loose triangle that frames the cross. Two hover at the level of Christ’s hands, another approaches from the left in partial shadow, and one kneels in the foreground, chalice poised beneath the cross. Their positions create a rhythm that leads the eye up and down the vertical axis: from the cup at the foot, along the wood, to the wounded hands with their golden vessels, and back toward the chalice-bearing cherubs in the clouds. The movement of looking becomes a devotional ascent and return, a visual analogue of prayer that contemplates the wounds and then descends to the earth where the blood touches human history.

Angels as Liturgical Ministers of the Passion

The most striking iconographic feature is the angels with chalices. Rubens reimagines the Crucifixion not simply as a historical event but as a perpetual offering. The putti are not spectators; they minister. One kneels in humble concentration, another leans forward with urgent tenderness, and a pair in the upper left whisper or sing, as if chanting the Sanctus. The chalices are unmistakably Eucharistic, their gold surfaces glinting against the gray-green air. In Catholic theology, the blood shed on Calvary is the very blood offered sacramentally in the Mass; the angels’ actions collapse time and space, revealing the altar hidden inside the cross.

This celestial liturgy also speaks to the intimacy of the divine economy. Angels become embodiments of what the faithful are asked to do spiritually: receive the grace that flows from Christ and offer it back in praise. Their smallness relative to the cross underscores the disproportion between human and divine action, while their sweetness softens the ferocity of nails and wounds. Rubens thus stages a paradox central to Baroque devotion: the infinite made close, the terrible made tender.

Light, Color, and the Atmosphere of Atonement

The palette is restricted and devotional. A world of warm grays, smoked golds, and pallid flesh tones surrounds Christ’s body, which glows with an inner light. The cloth around his waist reads as cool white with greenish shadows; the wood of the cross is brown-black, nearly swallowing the nails. The angels’ skin is rosier and their wings pearly, catching light at the edges like shells turned toward the sun.

Light operates symbolically as grace. It falls where the mystery is most concentrated—on the torso and wounds, on the reflecting chalices, on the kneeling angel’s face—and fades toward the margins where the earth horizon and Golgotha’s skull sit in shadow. The sky is not storm-wracked; rather, it is hushed and translucent, a diffusing veil through which the sacred action shines. With this restrained tonality Rubens avoids sensationalism and draws the viewer into contemplative attention. The muted atmosphere suggests that creation itself holds its breath as the new covenant is sealed.

The Body of Christ: Beauty, Suffering, and Theology

Rubens, a master of the human figure, paints Christ’s body with anatomical knowledge and spiritual intent. The thorax expands, ribs barely visible beneath taut skin; the abdomen softens above the knot of cloth; the thighs are weighty and real. The crown of thorns presses into the forehead, and thin streams of blood trail toward the eyes and beard. Yet the flesh is not disfigured beyond recognition. The artist’s famed sensuousness is disciplined to serve doctrine: the beauty of the form proclaims the dignity of the victim and the voluntary character of his self-offering.

This aesthetic choice carries theological weight. In Catholic and early modern spirituality, the contemplation of Christ’s wounds functions as a gateway to divine love. The viewer is meant to feel both sorrow and gratitude, to experience the shock that such a body is given up “for you.” The angels’ veneration corroborates this reading. Their chalices insist that the Passion is not merely an example of heroic endurance; it is an efficacious sacrifice whose fruits are communicable, drinkable, life-giving.

The Inscription and the Instruments of the Place

Above Christ’s head sits the placard of the titulus, its letters faint or lost in light, a white rectangle that flutters like parchment in wind. The absence of legible script paradoxically universalizes the proclamation “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews.” Rather than anchoring the scene in linguistic specificity, Rubens lets the blankness frame the Word made flesh.

At the foot of the cross lie discrete tokens. A skull rests on the ground, naming Golgotha, “the place of the skull,” and recalling Adam, whose death is undone by Christ’s new Adam. Near the skull a chalice on the earth mirrors the heavenly cups, as if to say that even the dust expects transubstantiation. The wood of the cross is bare, with simple grain, devoid of excessive ornament. These minimal instruments situate us firmly on Calvary while leaving space for the angels’ liturgy to expand.

Baroque Devotion and the Counter-Reformation Context

Rubens’s devotional Crucifixions participate in the broader visual culture of the Counter-Reformation, which emphasized clarity of doctrine, emotional engagement, and sacramental piety. This canvas answers all three aims. The doctrine is clear: the blood shed on the cross is the blood received in the chalice. The emotion is carefully guided: tenderness and reverence, not horror, lead the soul to thanksgiving. The sacramental piety is unmistakable: angels behave as ministers of the altar, and the entire sky becomes a sanctuary.

Such images were intended not only for churches but also for private chapels and princely or clerical collections. The scale and intimacy of the composition suggest a space where viewers could pray in front of the work as they prepared for Mass or meditated afterward. Rubens’s painterly skill, his speed, and the warmth of his palette make the theological message persuasive to the senses, bridging intellect and affection.

Painterly Surface and the Breath of the Brush

A close reading of the surface reveals the vitality of Rubens’s brushwork. The angels’ wings are feathered with quick, luminous strokes; the clouds are scumbled with thin veils of lead white and gray, allowing the ground to breathe through; the flesh of Christ is built with semi-transparent layers that allow warm underpaint to infuse the half-tones. Tiny catches of impasto sparkle on the rims of the chalices and along the thorny crown. The loincloth is drafted with confident, economical folds that twist in the breeze and hold the eye at the center of the body.

This tactile handling supports the spiritual intention. The viewer almost feels the softness of putto flesh, the cool metal of the cups, the roughness of wood—sensations that guide the imagination into the narrative. Rubens’s art insists that the Incarnation is not an abstraction; it enters the realm of touch, weight, and breath.

Silence, Sound, and the Angelic Choir

Though painting is a silent art, Rubens suggests sound through the postures of the angels. The two on the left seem to whisper; the one at the right lifts his cup as if at a cue; the kneeling angel gazes upward with parted lips, in a posture of “Amen.” One can almost hear the muted responses of a Mass, the murmur of prayer at the foot of the cross. Christ’s head is inclined in a way that reads as both exhaustion and listening, as though he hears the small voices of those who love him. The clouds become muffled acoustics for this heavenly liturgy, enclosing the action in a hush that dignifies the sacrifice.

Iconographic Echoes and Artistic Lineage

Rubens’s solution has precedents in late medieval imagery of the “Mass of St. Gregory,” in which Christ appears on the altar to affirm the Real Presence. It also echoes earlier Netherlandish paintings where angels catch the Precious Blood in chalices or ampullae. Yet Rubens modernizes the scheme with Baroque naturalism and motion. His Christ is not a rigid emblem but a living body whose muscles tire and whose skin cools under the gathering clouds. The angels are not hieratic attendants; they are children with weight, curiosity, and reverence. The synthesis of tradition and immediate sensation is characteristically Rubensian, making old theology feel newly seen.

The Viewer’s Place at the Foot of the Cross

Because the foreground angel kneels below the crossbeam and faces toward us, he becomes a proxy for the viewer. The cup he holds is near our space, its rim bright, inviting participation. In many devotional practices, the faithful imagined themselves at Calvary, offering their suffering and receiving grace. Rubens constructs that invitation visually. We are placed precisely where the blood meets earth, where the divine gift crosses into human need. The painting does not simply show a past event; it proposes an exchange that is happening now, between Christ and whoever stands before the canvas.

The Paradox of Majesty in Humility

Despite the absence of royal regalia, the image communicates kingship. Christ’s nakedness, the rough wood, and the modest cloth speak of humility; yet the centered composition, the steady vertical, and the angelic court confer majesty. The blank titulus, fluttering like a white banner, serves as a cryptic standard above the King. The message is paradoxical: power revealed in self-emptying, triumph in apparent defeat, banquet in the shedding of blood. Rubens thus translates Pauline theology into pictorial form, insisting that the wisdom of God appears as folly to the world and yet draws angels and humans alike to adoration.

From Calvary to the Altar: A Devotional Conclusion

Everything in the painting bends toward sacrament. The cross becomes an altar; the sky becomes a sanctuary; the angels become ministers; the chalices gleam with the promise that what is poured out will be poured into hearts. The skull on the ground recalls death’s reign; the chalice beside it announces that death has been drunk up and transformed into life. The restrained light, the gentle putti, the noble body—all conspire to change a scene of execution into a celebration of divine generosity.

In this way Rubens achieves a peculiarly Baroque miracle. He persuades the senses to consent to mystery. The eye delights in the flesh tones and the soft clouds, the gold vessels and the playful wings; the mind recognizes in these delights the signs of a deeper reality; the heart is moved to gratitude. “Christ Attended by Angels Holding Chalices” stands as a devotional engine, turning seeing into prayer and contemplation into participation, so that the beholder might leave the painting with the echo of the angels’ quiet responses still sounding within.