Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Anatomical Studies: A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm”

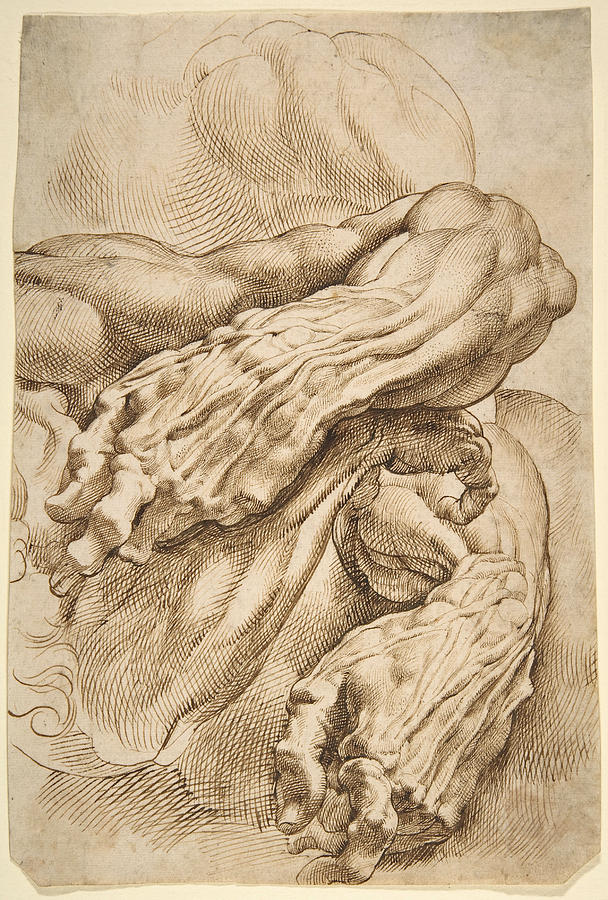

“Anatomical Studies: A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm” by Peter Paul Rubens is one of the most revealing sheets in the artist’s graphic oeuvre. Instead of a heroic saint or mythological god, Rubens concentrates solely on three massive forearms, twisting across the paper like living sculptures. The drawing offers a rare glimpse into the intellectual and technical labor that underpinned his grand Baroque paintings. Every tendon, vein, and wrinkle is pulled into sharp focus, turning a fragment of the human body into a powerful statement about strength, movement, and the discipline of artistic study.

Although the date is unknown, this work fits with Rubens’s lifelong habit of making focused anatomical drawings. They served as both exercises and reference material, ensuring that the dramatic gestures in his paintings rested on a foundation of anatomical truth. On this sheet the forearms are so enlarged and closely cropped that they almost lose their identity as parts of a body and become abstract rhythms of line and volume.

Rubens and the Discipline of Anatomical Drawing

Rubens was not only a court painter and diplomat but also a deeply learned draftsman who understood the importance of anatomy in visual storytelling. In the Baroque period, artists sought to convey intense emotion and dynamic movement, which demanded a precise knowledge of how the body twists, flexes, and strains. The forearm, with its complex interplay of muscles, tendons, and skin, was particularly important in conveying action, whether in a soldier raising a sword, an apostle gesturing in debate, or a martyr recoiling in pain.

This sheet shows Rubens treating anatomy as a subject worthy of sustained, almost obsessive attention. The poses he selects are not relaxed; the forearms are flexed, fingers curled, muscles taut. He is interested in the body under tension, the moment when physical effort transforms the surface of the skin into a map of underlying structures. Such studies were essential for his grand altarpieces and battle scenes, where arms and hands often carry the emotional weight of the composition.

Composition and Arrangement of the Forearms

At first glance, the drawing appears almost chaotic, a tangle of limbs and contours. Closer inspection reveals a deliberate arrangement. Two left forearms dominate the center, shown in different positions and foreshortening, while a right forearm enters from below. They overlap and crisscross, forming a dense knot of forms that fills nearly the entire page. There is no background, no torso, and no hint of a narrative context. The limbs occupy the sheet like geological formations, monumental and self-contained.

The diagonal thrust of the principal arm drives the composition from upper right to lower left, creating a sense of energetic movement even though the forms are static. The repetition of similar structures in different rotations allows the viewer to compare the way muscles shift with each change of angle. In this way the sheet functions almost like a rotating model, frozen at three crucial moments.

The absence of a complete figure intensifies the viewer’s focus. Rubens is not interested here in ideal beauty or graceful proportion; what matters is the sensation of weight, strain, and the tactile reality of flesh. By cropping so tightly, he compels us to look closely at the anatomy itself.

Line, Hatching, and the Illusion of Volume

The technical brilliance of the drawing lies in Rubens’s handling of line. Using pen and brown ink, he constructs the arms through dense networks of parallel and cross-hatched strokes. These lines follow the direction of the muscles and the curvature of the skin, wrapping around the forms as if they were three-dimensional. The result is a remarkably sculptural effect; the forearms seem to project out of the paper, each ridge and hollow carefully modeled by line alone.

Rubens varies the thickness and spacing of his strokes to suggest different textures and levels of shadow. In deep creases and recessed areas he lays down dense, dark hatching, while on raised muscles the lines are lighter and more widely spaced, letting the paper shine through as highlight. Long, sweeping strokes define the broad planes of the biceps and forearm, while shorter, jagged strokes articulate the knuckles and wrinkled skin of the fingers.

Behind and around the arms, he draws loose, curving lines that echo the forms without describing any specific object. These background strokes suggest the rounded mass of a torso or shoulder, but they remain deliberately vague. Their main purpose is compositional: they soften the transition between the solid limbs and the blank paper, and they add an almost atmospheric vibration around the dense central cluster.

Musculature, Tendons, and Surface Detail

What makes this sheet so compelling is the intensity with which Rubens observes and records the forearm’s structure. The muscles swell and taper with convincing rhythm; tendons stretch in taut bands across the back of the hand; veins wind subtly beneath the skin’s surface. The fingers are gnarled and bony, their tips curling inward in a way that conveys both power and wear.

The skin is not smooth. Rubens pays careful attention to wrinkles at the wrist, folds on the back of the hand, and the slight bunching of flesh where the forearm bends. These surface details are not decorative; they reveal how the underlying anatomy presses against the skin. Especially striking are the exaggerated ridges along the backs of the hands and fingers. They almost resemble tree roots or twisted ropes, emphasizing the strain of gripping or pushing.

By focusing on such details, Rubens transforms the drawing into a study of how energy manifests itself in bodily form. The arms do not simply exist; they act, exert, and resist. Even without seeing what the hands grasp or push against, we feel the effort.

Expressive Qualities and the Drama of the Body

Although the drawing is ostensibly a neutral anatomical study, it carries a strong emotional charge. The contorted fingers and bulging veins suggest struggle or labor; these could be the arms of a martyr, a hero in battle, or a worker lifting a heavy weight. Rubens, master of Baroque drama, cannot help infusing even a fragmentary study with expressive life.

The overlapping arrangement of the limbs adds to this sense of drama. It is almost as if several arms are simultaneously engaged in a violent action just outside the viewer’s field of vision. The viewer might imagine a tightly packed group of figures, each straining in a different direction. In this way the drawing anticipates the crowded, swirling compositions of Rubens’s finished canvases.

At the same time, there is a certain austerity. The absence of faces, clothing, or background story strips the scene down to pure physicality. What remains is the raw, universal language of effort. The hands and forearms communicate emotion not through facial expression but through the choreography of muscles and tendons.

Relationship to Rubens’s Painting Practice

This sheet was almost certainly part of Rubens’s working archive, a resource he could consult when designing large-scale paintings. His altarpieces, mythological cycles, and battle scenes are filled with complex poses in which arms carry weapons, embrace companions, or reach toward heaven. To choreograph such actions convincingly, he needed a mental library of how the forearm behaves in extreme positions.

In many of his paintings, we can detect echoes of studies like this one. Soldiers in “The Elevation of the Cross” or executioners in martyrs’ scenes display similarly tense and wrinkled hands. The exaggeration of surface detail in the drawing—the rope-like veins and knotted fingers—prepares him to heighten physical drama on the canvas when narrative demands it.

For Rubens, drawing was a laboratory where he could experiment without the pressure of public display. “Anatomical Studies: A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm” reveals the analytical underpinnings of his theatrical style. The wild energy of his compositions rests on a solid understanding of basics, tested repeatedly on sheets like this.

Dialogue with Renaissance and Classical Models

Rubens’s interest in anatomical study was nourished by earlier masters. During his Italian period, he studied Michelangelo’s frescoes and sculptures, whose muscular figures set a standard for expressive anatomy. The exaggerated forms in this drawing, particularly the swollen muscles and dynamic contours, recall Michelangelo’s powerful ignudi and prophets. Rubens translates that tradition into the language of pen and ink, turning stone and fresco into line and hatching.

At the same time, the sheet reflects his engagement with antique sculpture. Classical fragments, torsos, and limbs found in Italian collections provided him with endless material for study. The monumental scale and somewhat idealized structure of the arms suggest that he may have based them partly on sculptural models, then animated them with the added detail of living skin.

What distinguishes Rubens, however, is his tendency to push anatomy beyond idealization toward expressive distortion. The hands in this drawing are more rugged and wrinkled than most classical examples, more human in their imperfections. In fusing classical monumentality with close observation, he creates a uniquely Baroque kind of anatomical study.

The Sheet as an Independent Work of Art

Although created as a study, this drawing has an aesthetic value independent of its function. The flow of lines, the play of light and shadow, and the rhythmic repetition of forms produce a kind of abstract beauty. One can appreciate it simply as a composition of curves and textures, without reference to its anatomical content.

The viewer’s eye travels along the sinuous contours of the arms, dips into the dark pockets of shadow between overlapping muscles, and then rises again along lighter planes. The pattern of hatching, especially in the background, creates a sense of movement across the paper, almost like ripples on water. In this sense, the drawing operates on two levels at once: it is both a precise anatomical record and an expressive design.

The physical condition of the sheet—the slight discoloration of the paper, the irregular edges—also contributes to its charm. We feel close to the artist at work, imagining him turning the sheet, testing different pressures of the pen, and adjusting the arrangement of limbs as he refines his understanding.

Insight into Rubens’s Mind and Method

Studying this drawing allows us to glimpse Rubens’s mental process. He does not start from an abstract theory of anatomy; instead, he builds knowledge through repeated, careful observation. The two versions of the left forearm demonstrate comparative thinking. By placing them side by side, he can analyze how rotating the arm changes the interplay of muscles, where the tendons stand out, and how skin stretches or compresses.

The decision to add a right forearm below the others shows a mind constantly seeking variation. Perhaps he realized that a different perspective or configuration would be useful for other compositions. Each arm is self-contained yet part of a broader investigation into how limbs behave in space.

This methodical curiosity reflects a broader intellectual culture in Rubens’s time, when artists were also amateur scientists. Anatomy, optics, and geometry were not separate from art; they were essential to creating convincing illusions. “Anatomical Studies: A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm” is a visual record of such interdisciplinary thinking.

Conclusion

“Anatomical Studies: A Left Forearm in Two Positions and a Right Forearm” is a powerful testament to Peter Paul Rubens’s commitment to understanding the human body in depth. Through dense hatching, precise contour lines, and a keen eye for muscular structure, he turns three forearms into a drama of flesh, effort, and form. The drawing stands at the crossroads of science and art, serving as both working tool and self-sufficient masterpiece.

In isolating and magnifying these limbs, Rubens invites viewers to consider how much emotion and narrative can be carried by a single part of the body. The sheet reveals the hidden foundation beneath his grand canvases: rigorous study, patient observation, and a fascination with the expressive possibilities of anatomy. Today, it continues to captivate artists, historians, and admirers of drawing as a vivid display of Baroque intelligence and craft.