Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Putti Testing a Man’s Perception of Depth”

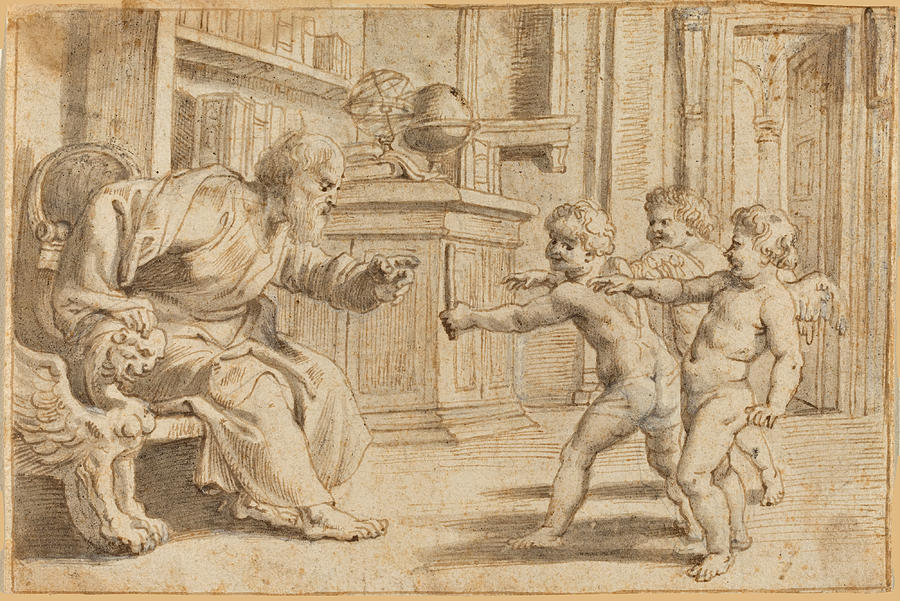

“Putti Testing a Man’s Perception of Depth” is a small but intellectually rich work attributed to Peter Paul Rubens. Executed as a drawing or monochrome study rather than a full-color canvas, it presents an elderly scholar seated in a sumptuous chair, confronted by three mischievous winged putti. The scene plays out in a learned interior filled with books, a celestial globe, and architectural details that emphasize linear perspective.

At first glance the work looks playful: chubby children approach an old man as if in a game. The title, however, hints that something more complex is taking place. Rubens appears to be exploring how the human eye perceives space, distance, and overlapping forms, and he does so by placing a philosophical figure in direct conversation with visual tricksters. The drawing becomes both a study of depth in pictorial terms and an allegory of how perception and knowledge interact.

The Learned Interior And Its Significance

The background of the drawing situates the action firmly in the world of scholarship. Behind the seated man, shelves are packed with books, their spines rhythmically aligned. On top of a substantial cabinet or lectern sits a large globe, most likely celestial rather than terrestrial, given its position in a philosopher’s study. These objects immediately signal that the central figure is an intellectual—perhaps a mathematician, astronomer, or natural philosopher.

The architecture reinforces this impression. We see high doors, pilasters, and a receding tiled floor that leads the eye back into space. Rubens uses strong linear perspective to draw the viewer’s gaze past the foreground figures towards the depth of the room. The combination of books, globe, and ordered architecture suggests a universe governed by rational laws and accessible through study and careful observation.

Against this ordered environment, the lively putti introduce an element of unpredictability. While the scholar’s world is composed of straight lines, grids, and codified knowledge, the putti move in curves, their bodies full of soft volumes and organic energy. The drawing thus sets up a contrast between the stability of accumulated learning and the fluid, experimental nature of perception and play.

The Seated Scholar: Embodiment Of Reason

The old man seated on the left is rendered with particular care. His beard and hair are wispy and thin, his forehead deeply furrowed, and his posture slightly stooped, all of which convey age and long experience. His clothing consists of ample robes that fall in heavy folds, emphasizing his immobility compared to the lively children before him.

He sits on an elaborate chair whose arms terminate in winged lion heads, a traditional symbol of strength, wisdom, and perhaps evangelist authority. The very chair links him to venerable traditions and suggests that his position is not only intellectual but also moral or spiritual.

Most important is his gesture. Leaning forward, he extends one hand toward the foremost putto, index finger pointing as if testing the child’s distance or trying to touch him. His other hand supports him on the chair, indicating that this motion requires effort. His expression appears intent, almost skeptical. He is not merely smiling at childish antics; he is scrutinizing, measuring, and judging what he sees.

In the context of the title, the scholar represents disciplined reason under examination. His perception of depth is being “tested,” not by instruments or geometric diagrams, but by the animated bodies of the putti, who inhabit the same space yet play by different visual rules.

The Putti As Agents Of Perception

Three winged putti stand opposite the scholar, moving toward him in a staggered line. Their small wings identify them as more than ordinary children; they belong to the traditional vocabulary of Renaissance and Baroque art in which putti can represent love, inspiration, senses, or even the invisible forces of nature.

The foremost putto extends both arms, palms open, walking toward the scholar with determined steps. His body leans forward, feet spread, as if exerting effort to bridge the gap. The second putto follows closely behind, a hand resting on the shoulder of the first, while the third stands slightly farther back, also engaged but less prominent. This ordering creates an overlapping sequence that visually demonstrates depth: near, middle, and far.

In a playful way, the putti enact a lesson in perspective. By overlapping their bodies and staggering their positions, Rubens creates a receding rhythm that helps the viewer understand spatial relationships. The very act of one putto touching the other’s shoulder emphasizes continuity in space—each is separate yet connected, much as different planes of depth in a drawing relate to each other.

At the same time, the putti are testing the scholar. Are they approaching him from a true distance or simply appearing nearer because of perceptual tricks? Their gestures suggest both invitation and challenge, as if saying: “Can your learned mind grasp not only abstractions but also the immediate experience of space in front of you?”

Depth And Perspective In The Drawing Itself

Beyond the depicted experiment, Rubens uses the drawing to explore depth on the sheet of paper. The tiled floor receding toward the right, the raking lines of the cabinets, and the diminishing size of architectural elements all work together to establish a convincing three-dimensional space.

The scholar occupies a firmly defined foreground zone, his chair placed at an angle that echoes the perspective grid of the floor. The putti stand slightly further back, yet they are still in the front half of the room. Behind them rise the cabinets and the doorway leading into another chamber. Rubens thus uses multiple layers: the viewer’s space outside the drawing, the scholar’s zone, the putti’s approach, and the recessive background.

Line work plays a crucial role. Cross-hatching darkens areas under the table, behind the shelves, and within folds of drapery, pushing them back. Lighter, more open hatching describes surfaces closer to the viewer. Rubens’s control of tonal value, even in a monochrome medium, allows him to model both volume and distance.

The title “Putti Testing a Man’s Perception of Depth” can therefore be understood in a meta-artistic sense: the drawing itself is a test of how far shading, perspective, and overlapping figures can persuade an observer to experience depth on a flat page.

Allegory Of Knowledge And The Limits Of Reason

Beyond formal experimentation, the drawing carries an allegorical charge. The scholar, surrounded by books and instruments, stands for accumulated knowledge—geometry, astronomy, philosophy. He is the personification of the learned intellect. Yet his knowledge is mediated through texts and models; the books and globe are abstractions of reality.

The putti, in contrast, come from the realm of immediate experience and perhaps divine inspiration. They are barefoot, naked, and unencumbered by material objects. Their testing of depth may hint at the way perception and intuition can challenge or expand the boundaries of purely bookish understanding.

The scholar’s forward lean and extended finger suggest recognition that to truly know, he must engage not just with symbols and diagrams but with living phenomena. The children’s approach embodies the world’s insistence on being experienced directly, not merely described. In this reading, the drawing becomes an allegory of how the senses and imagination correct and enrich intellectual systems.

The Role Of Play And Experiment

The encounter between the old man and the cherubs is laced with humor. The contrast between his serious concentration and their carefree movement suggests a scenario where play becomes a form of experiment. This aligns with early modern scientific culture, which began to value observation, experiment, and even “trials” that might resemble games or demonstrations.

The putti can be seen as animated hypotheses. Their movement across the room tests whether the scholar’s theories about depth and vision hold up when confronted with shifting bodies. At the same time, their playfulness reminds us that learning often occurs through curiosity and interaction rather than solemn contemplation alone.

Rubens, who moved in humanist and courtly circles, knew that patrons appreciated images that combined wit and instruction. A drawing like this could delight viewers with its charming figures while also provoking thought about how we come to know the world.

Stylistic Features And Rubens’s Draftsmanship

The drawing demonstrates Rubens’s mastery of line and his ability to imply texture and weight within a small format. The robes of the scholar are composed of long, sweeping contours that break into quick internal folds, suggesting heavy fabric. The putti’s bodies, by contrast, are modelled with shorter curves and softer hatching, emphasizing plumpness and youth.

Rubens achieves a sense of light streaming from the left side of the image. Highlights along the scholar’s head, the globe, and the putti’s shoulders indicate the direction of this light source. Shadows fall under the furniture and on the far side of each figure, further solidifying their presence in space.

The precision of architectural lines—doorframes, shelf edges, baseboards—contrasts with the more organic flow of figures. This tension between rigid geometry and supple anatomy is a hallmark of Rubens’s style, one that allows him to stage human drama within convincingly constructed spaces.

The medium itself, likely pen and ink with wash on paper, contributes to the intimate, exploratory character of the work. It feels like a conceptual sketch, possibly part of a larger program or a design for a print or painting, in which Rubens tested ideas about allegory, composition, and spatial illusion.

Humanism, Classical Learning, And The Image Of The Philosopher

In the seventeenth century, the figure of the philosopher or sage in his study was a familiar motif. Such images celebrated classical learning revived by Renaissance humanism. The books and globe in Rubens’s drawing echo portraits of scholars, astronomers, and theologians who were portrayed surrounded by their tools of knowledge.

By introducing putti into this venerable image-type, Rubens freshens the theme. The philosophical study becomes a stage where classical notions of wisdom meet newer ideas about experimentation and perception. The putti themselves, rooted in antique imagery of Eros and attendants of the gods, reinforce the humanist connection to antiquity while injecting it with Baroque liveliness.

The specific discipline of the scholar is left ambiguous—he could be a mathematician testing Euclidean theories of optics or a general philosopher reflecting on the limits of sense perception. This ambiguity allows the scene to speak to a broad set of concerns about how humans interpret the visible world.

Viewer Engagement And Visual Irony

The drawing quietly implicates the viewer in its exploration of depth. As we look at the scene, we are ourselves engaged in perceiving spatial relationships: how far the scholar sits from the putti, how deep the room is, how objects overlap. Our own perception of depth is being tested by the same cues that the imagined philosopher contemplates.

There is a mild irony in this arrangement. The scholar, who represents sophisticated understanding, is in some sense in the same position as we are—trying to make sense of what he sees. The putti’s experiment with him is mirrored by Rubens’s experiment with us. The artwork thus becomes a layered play on seeing and knowing: a study about perception that operates through our own perception.

Conclusion: A Small Drawing With Large Ideas

“Putti Testing a Man’s Perception of Depth” may be modest in scale and monochrome in palette, but it is conceptually rich. Rubens uses a simple scene—a scholar and three putti in a study—to explore how depth is represented on paper, how the senses interact with reason, and how play can serve as a mode of inquiry.

The carefully constructed interior, the staggered positions of the putti, and the concentrated expression of the old man all work together to create a visual dialogue between knowledge and experience. Rubens’s deft draftsmanship makes the space convincing, while his imaginative arrangement of figures gives the drawing allegorical resonance.

Viewed today, the work reminds us that questions about perception, illusion, and the reliability of our senses are not new. They fascinated artists and thinkers in Rubens’s time just as they do now. Through this charming yet sophisticated drawing, Rubens invites us to join the putti and the philosopher in considering how we see the world—and how the world, in turn, tests the limits of our seeing.