Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “The Statue of Ceres”

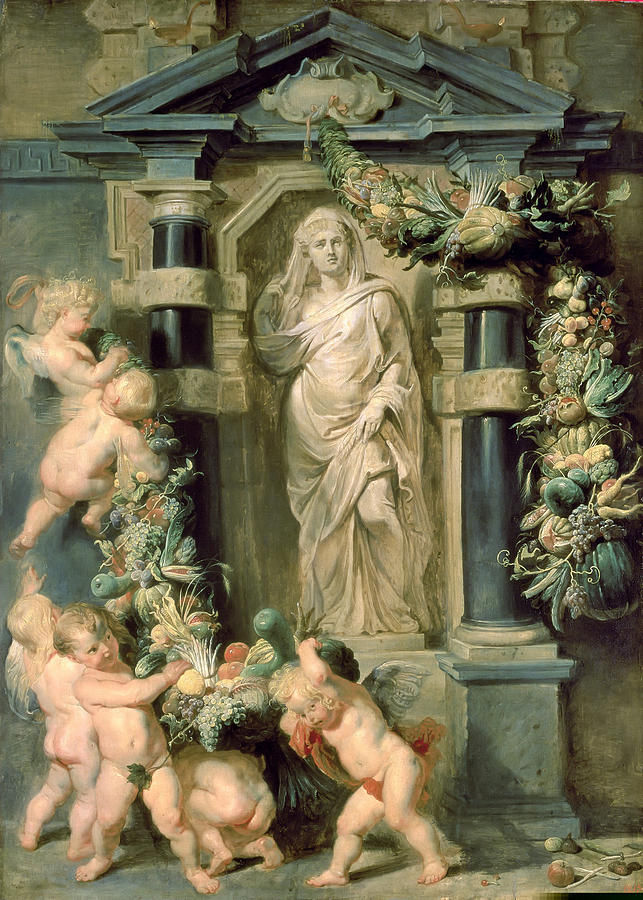

“The Statue of Ceres” by Peter Paul Rubens is a dazzling meditation on abundance, classical antiquity, and the animated power of painting. At first glance the work seems to show a marble niche with a statue of the Roman goddess of agriculture, framed by a heavy architectural setting. Yet the stone stillness of Ceres is surrounded by lively putti who hoist garlands overflowing with fruits and vegetables. The contrast between cold sculpture and warm, rosy flesh is central to Rubens’ idea: painting can bring to life what stone can only suggest, turning a static monument into a celebration of fertility and joy.

The date of the painting is unknown, but stylistically it fits with Rubens’ mature Antwerp period, when he was immersed in classical themes and collaborating with other artists on decorative cycles. “The Statue of Ceres” likely formed part of a series of allegorical works celebrating the seasons, fertility, or the prosperity of a patron’s estate. Rubens uses the subject to display his virtuosity in figure painting, still life, and architectural illusionism at once.

Ceres and the Classical Theme of Fertility

In Roman mythology, Ceres is the goddess of agriculture, grain, and the fruitful earth, closely related to the Greek Demeter. She presides over the cycles of sowing and harvest, and her favor ensures plenty. Artists and patrons in the Baroque period frequently invoked Ceres as an emblem of prosperity, good governance, and natural bounty. To have Ceres present—whether in sculpture or painting—was to proclaim that one lived in a land blessed by rich harvests and political stability.

Rubens, a renowned humanist as well as painter, would have known ancient texts and images of Ceres. In this painting he deliberately presents her as a classical marble statue: draped in heavy folds, standing in a niche between columns, her expression serene and somewhat remote. She raises one hand in a modest gesture, the other resting on her drapery. This sculptural pose evokes antique temple statues and also reflects the kind of Roman marbles Rubens studied and collected.

Yet Rubens does not stop at archaeological accuracy. By surrounding the statue with chubby, energetic putti who handle overflowing garlands of fruits, he translates the abstract concept of fertility into a tangible, playful scene. The viewer senses not only reverence for antiquity but also delight in the physical pleasures that Ceres bestows: ripe grapes, melons, gourds, and grains.

Architectural Illusion and the Central Niche

The setting of “The Statue of Ceres” is itself a work of imagination. Rubens constructs a grand niche with pediment, columns, and plinths, all rendered in cool stone tones. Two dark columns flank the central figure, supporting an entablature and triangular pediment decorated with scrolls and cartouches. The architecture feels solid and weighty, occupying believable space. It frames Ceres like an altar, turning the painting into a kind of fictive chapel dedicated to the goddess.

Rubens uses this architecture to play with illusion. At first, the viewer might mistake the entire image for a depiction of an actual stone monument. But the warm colors and animated poses of the putti quickly undermine that first impression. They are clearly living beings, not carved decorations. Some of them climb up the column bases, others tug at the garlands that hang from the pediment, as if they might topple the architectural structure with their exuberance.

This interplay between the static stone and the animated children highlights one of Rubens’ favorite themes: the superiority of painting in representing both texture and movement. He can convincingly imitate cold marble while simultaneously showing what marble cannot do—move, laugh, and strain with effort. The niche becomes a stage on which painting demonstrates its power to outdo sculpture.

The Statue of Ceres: Stillness and Dignity

Within the central niche, Ceres herself is depicted as a classicizing marble figure. Unlike the rosy putti, she is bathed in a pale, almost monochrome light that suggests carved stone. Her drapery cascades in heavy folds, covering most of her body; only the oval of her face and a bare foot peeking from below hint at the human form beneath. Rubens uses subtle shifts in tone to model the statue’s surface, capturing both the weight of the garment and the slight wear of time on stone.

Her pose is dignified and reserved. One arm is raised near her head, the other gently gathers her mantle, creating a soft diagonal that leads the eye downward. Her expression is calm, almost introspective, as if she is unaware of the lively activity happening around her pedestal. This aloofness is fitting for a goddess who embodies enduring natural cycles rather than fleeting emotions.

By keeping Ceres still and monochromatic, Rubens allows the viewer to experience her as both an artwork within the painting and as a divine presence. She is the source of the bounty represented by the garlands of produce, yet she appears self-contained, eternal. The putti behave almost like altar servants decorating her shrine for a festival.

Putti at Play: Movement and Human Warmth

The lower half of the painting bursts with activity. A group of putti—plump, naked children with tiny wings—struggle playfully to carry and adjust the heavy garlands of fruit and vegetables. Their bodies twist in various directions; one child stoops to lift a laden bundle, another strains upward, another looks back at his companions. Rubens revels in depicting the soft roundness of their limbs, the folds of baby fat, and the way muscles bunch as they push and pull.

These putti are not idealized angels but very human toddlers, with flushed cheeks and clumsy movements. Their innocence and energy create a lively counterpoint to the solemn stone goddess above. At the same time, their actions have ritual overtones. In ancient and Renaissance imagery, putti often appear as attendants to gods or personifications, performing tasks like wreath-laying, torch-bearing, or pouring libations. Here they decorate Ceres’ shrine, enacting a festival of abundance.

Rubens’ handling of their flesh is masterful. Warm pinks and creamy whites are modeled with subtle shadows, creating a sense of softness and volume. Highlights on knees, bellies, and shoulders suggest healthy skin catching the light. Even the slight wobble of their stance is captured—one child’s toes press into the ground, another’s heel lifts mid-step—making them feel completely alive.

The Garlands of Fruit and Vegetables

The garlands that the putti maneuver are themselves a marvel of still-life painting. Rubens fills them with an astonishing variety of produce: grapes, pomegranates, melons, squashes, pears, cabbages, artichokes, and more. Each fruit is recognizable, yet all are woven together into a unified decorative rhythm that loops around the niche. The sheer abundance of different shapes and colors reinforces the theme of overflowing fertility.

Rubens uses color to distinguish the natural bounty from the cool stone architecture. The fruits and vegetables are painted in rich greens, golds, reds, and purples, with glistening highlights that suggest freshness. Dewy grapes catch the light, their translucent skins reflecting the surrounding hues. The rough textures of gourds and cabbages contrast with the smooth surfaces of apples and pears.

The garlands are not static; they sag under their own weight, twist as the putti pull on them, and cast shadows on the stone. This sense of weight and movement adds to the realism of the scene. At the same time, the garlands function symbolically: they are offerings to Ceres and visible proof of her generosity. In a broader sense, they stand for the prosperity of the painting’s patron and the land he owns or governs.

Color, Light, and Atmosphere

The overall color scheme of “The Statue of Ceres” is dominated by cool bluish greens and pale stone tones, punctuated by the warm flesh of the putti and the saturated hues of the fruits. Rubens orchestrates these colors to create a harmonious, slightly dreamlike atmosphere. The architecture recedes into cool shadow, while the foreground figures and garlands are bathed in a softer, warmer light.

Light appears to come from the upper left, illuminating the left half of the niche and the bodies of the children. Highlights on column edges, garland leaves, and cherub limbs create a lively play of reflections. Yet the painting is not starkly contrasted; shadows are transparent, allowing underlying colors to glow through. This soft lighting enhances the sense of a festive, almost theatrical setting rather than a harshly sunlit shrine.

Rubens’ brushwork varies across the canvas. In the fruits and leaves he uses quick, expressive strokes to suggest texture and sheen. In the putti’s flesh the paint is blended smoothly, with just enough visible brush mark to retain vitality. In the stone architecture he employs more restrained, linear modeling, reinforcing the impression of solid construction. This variety in handling keeps the viewer’s eye engaged as it moves from one material to another.

Allegory of Abundance and Good Governance

Beyond its immediate visual appeal, “The Statue of Ceres” likely held allegorical meaning. Ceres, as goddess of agriculture, is a natural emblem of abundance and peace. In classical and Renaissance political thought, flourishing crops and full granaries were signs of wise and just governance. By showing the statue of Ceres richly adorned with harvest offerings, Rubens may be paying compliment to a patron whose rule or stewardship brought prosperity to his lands.

The playful putti reinforce this message in a more lighthearted way. Their carefree labor suggests that under Ceres’ (and by extension the patron’s) benevolent influence, work itself becomes joyful rather than burdensome. Children can participate in the harvest, and nature gives generously without resistance. The lack of any threatening or destructive element—the scene contains no storm clouds, predatory animals, or signs of decay—emphasizes a utopian vision of well-ordered plenty.

At the same time, the preserved yet lifeless statue of Ceres reminds viewers that such abundance rests on enduring principles: reverence for nature, cyclical rhythms of seedtime and harvest, and the importance of honoring the forces that sustain life. The painting thus balances exuberant celebration with a hint of solemnity.

Dialogue Between Painting and Sculpture

One of the most fascinating aspects of this work is its self-conscious dialogue between painting and sculpture. Rubens was an ardent admirer of ancient sculpture, and he collected casts and marbles in his Antwerp home. Yet as a painter, he also delighted in showing how his medium could rival and surpass stone.

In “The Statue of Ceres,” he does so by creating a convincing illusion of a marble statue, but then surrounding it with elements that only painting can truly render: the translucency of grapes, the delicate sheen of leafy greens, the softness of infant skin. The viewer is invited to compare the unyielding surface of the carved goddess with the glowing, mutable forms of the living figures and organic garlands.

This comparison underscores a broader Baroque interest in the boundaries between the arts. Painters like Rubens and sculptors like Bernini sought to create works that seemed to come alive, dissolving the distinction between representation and reality. By embedding a “sculpture” within his painting, Rubens participates in this debate, demonstrating that paint on canvas can evoke the full range of sensory experiences—from weighty stone to tender flesh—even more effectively than actual marble.

Place Within Rubens’ Oeuvre

“The Statue of Ceres” belongs to a group of works in which Rubens integrates mythological figures, putti, and lavish still life elements within architectural settings. These compositions may have served as designs for decorative panels in palaces, hunting lodges, or allegorical cycles celebrating peace and prosperity. The combination of classical goddesses with fruit garlands appears elsewhere in his work, sometimes in collaboration with still-life specialists.

The painting also reveals Rubens’ sustained interest in the theme of abundance. Across his oeuvre, from “The Four Continents” to scenes of Bacchus and satyrs, he repeatedly explores overflowing riches of nature—wine, fruit, game, and luxuriant bodies. Ceres, as patroness of grain and harvest, fits seamlessly into this visual world.

For modern viewers, “The Statue of Ceres” offers a concise summary of many Rubensian qualities: love of classical antiquity, joy in painting the human body, fascination with textures and materials, and an optimistic outlook on the gifts of nature. It may lack the dramatic narrative of his large altarpieces, but it compensates with intimate charm and layered symbolism.

Conclusion

“The Statue of Ceres” by Peter Paul Rubens is far more than a depiction of a goddess in stone. It is a sophisticated meditation on fertility, festivity, and the creative power of art itself. Within a carefully constructed architectural framework, Rubens juxtaposes the marble stillness of Ceres with the animated exuberance of putti and the vibrant abundance of harvest garlands. The result is a composition that celebrates both nature’s generosity and painting’s ability to bring that generosity to life.

Through sensitive use of color, light, and texture, Rubens invites viewers into a world where stone niches become stages for living drama, where the gifts of the earth overflow in joyous plenty, and where classical myth serves as a vehicle for praising contemporary prosperity. “The Statue of Ceres” stands as a testament to his extraordinary skill and his enduring belief that art can transform lifeless matter into a vision of warmth, movement, and divine favor.