Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

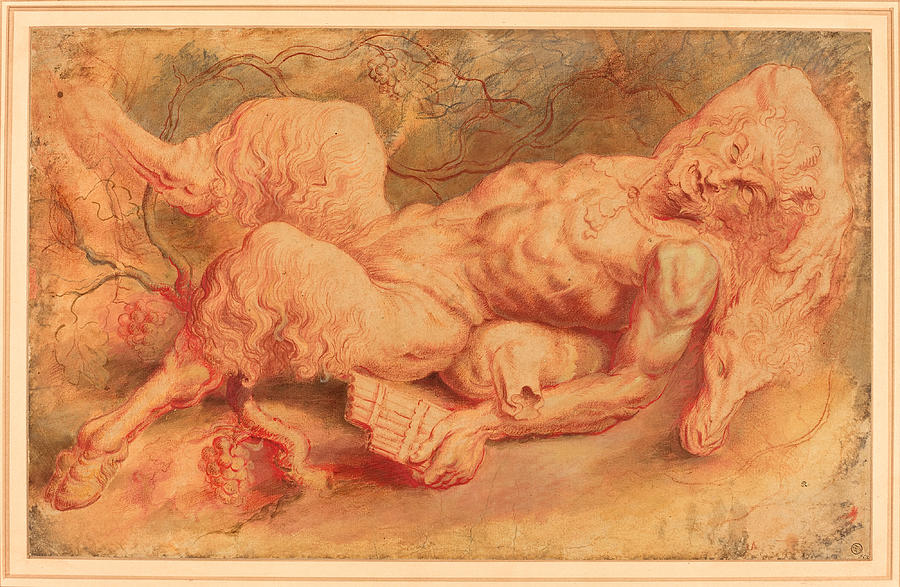

Peter Paul Rubens’s “Pan Reclining” (1610) is a luminous fusion of drawing and painting that renders the rustic god in a state of drowsy abandon. Executed in red and black chalk heightened with bodycolor, and then toned with translucent washes, the sheet radiates warmth and breath, as if Pan had been surprised in a sun-struck glade after a revel. His goat legs fold under a weighty, muscular torso; one hand holds a set of pipes; the great bearded head rests on a shaggy animal pelt. Vines creep across the background and clusters of grapes punctuate the ground like little embers. The paper itself seems to glow—coral, peach, and honey tones shaping the flesh while cooler mossy washes drift behind. In this single figure Rubens compresses antiquity, pastoral myth, and his own Venetian-honed colorism, turning a reclining study into a complete pastoral drama.

Rubens in 1610 and the Return to Antwerp

The year 1610 finds Rubens freshly back in Antwerp after a decade in Italy. He had absorbed the heroic anatomy of Michelangelo, the chromatic sumptuousness of Titian and Veronese, and the living classicism of the Carracci. In Antwerp he moved quickly to become the city’s dominant painter, producing altarpieces, portraits, mythologies, and a stream of preparatory drawings and oil sketches that were artworks in their own right. “Pan Reclining” belongs to this moment of synthesis. It wears its classical learning lightly: the brawny torso recalls antique river gods and satyrs, yet the drawing is flavored with Northern immediacy and Rubens’s taste for tactile flesh. The sheet is both a study in form and an autonomous pastoral reverie, evidence of how Rubens could make invention and observation meet on paper.

Composition and the Arc of Repose

The composition is built around a generous diagonal that runs from Pan’s raised knee at upper left down through the ribcage, over the sloped belly, to the head cushioned at lower right. This diagonal is countered by the angle of the pipes and by the curve of the tail that flicks back into space, creating an elastic S-curve that keeps the reclining figure from feeling inert. Pan’s legs are gathered like a spring compressed after dance; the long torso opens like a river bend; the head lolls into sleep with the weight of wine and music. Vines in the background echo these meanders, threading the page with tendrils that make the white ground feel like warm air. Rubens has composed not merely a body at rest but a landscape of relaxation—every curve and counter-curve orchestrates a visual sigh.

Anatomy as Allegory of Nature

Rubens’s anatomical invention animates Pan with a vitality that transcends study. The deltoid, biceps, and forearm are modeled in quick, swelling planes; the pectorals soften toward the sternum; the abdomen ripples with relaxed power; and the goat legs boast thick, sinewy thighs that taper to cloven hooves. This is not the refined body of an Olympian; it is earthier and more tactile, the musculature a little knotty, the belly gently loosened by wine. The hybrid anatomy functions as allegory: Pan’s human trunk speaks to wit and music; the caprine quarters proclaim appetite and the untamed. The body therefore enacts the theme of the pastoral—culture and nature in concert, not at war. Rubens’s confident handling invites the viewer to feel warmth, weight, and softness, the very properties that make the rustic god credible.

The Panpipes and the Drama of Silence

Pan’s right hand encloses a set of syrinx pipes, the instrument associated with seduction, dance, and the ancient story of the nymph who became reed. Held loosely against the belly, the pipes are temporarily mute, turning the drawing into a drama of aftermath. We sense the music that has just receded; the pose is that of a musician who has played himself to contented stillness. Rubens shapes the instrument with a few decisive strokes, allowing the hand’s knuckles and tendons to do most of the expressive work. The quiet of the scene is audible because the hand, so adept and strong, has relaxed its claim on sound.

Sleep, Wine, and the Pastoral Mood

The clusters of grapes that flank Pan, and the vine that meanders above him, declare the god’s vine-crowned festival kinship with Dionysus. But Rubens avoids frenzy. Instead of bacchic tumult, the mood is late afternoon: the glow of skin suggests heat cooling, the eyelids sink, and the heavy head finds a pelt for pillow. A faint smile turns the corner of the mouth, shadowed by the beard. The pastoral here is not innocence but seasoned ease—the body that has exerted itself and is now owned by its own contentment. Pan’s slumber is not moralized; it is presented as a natural rhythm: play, food, wine, and rest. The drawing thereby becomes a small manifesto of embodied pleasure that seventeenth-century collectors, steeped in classical texts, would have recognized as a worthy theme.

Materials, Technique, and the Glow of the Sheet

“Pan Reclining” dazzles as a demonstration of mixed media finesse. Rubens draws with red chalk to lay in the broad anatomy, then reinforces contours and shadows with black chalk. Over this foundation he lays warm washes—brick, peach, and diluted ochres—that seep into the paper’s fiber, producing a warm bath of color. Heightening with opaque white or bodycolor touches the most sunstruck planes—shoulder, knee, ridge of belly—so that the figure shines as if light were caught in the paper itself. The fluttering twigs and vines are sketched with a more transparent hand, allowing the background to breathe. This layered procedure marries drawing’s immediacy to painting’s atmospheric unity. The result is an object that glows from within, more like a living piece of flesh and air than a diagram of a god.

Venetian Color Remembered on Paper

Rubens’s Italian apprenticeship, particularly in Venice, taught him how color can build form without extinguishing vibrancy. On this sheet, the Venetian lesson is everywhere. Flesh is not modeled by gray shadow alone but by warm transitions—coral to rose to tawny gold—so the figure remains tonally vibrant even where it darkens. The background greens are subdued and mossy, a foil to the rosy body; the grapes pick up the warmer key in deeper ruby notes. Such coloristic tact ensures that the figure does not sit atop the world but participates in its climate. The eye reads not “colored drawing of a statue” but “warm body reclining in filtered light.”

Lines of Energy and the Living Contour

Rubens’s contour is neither rigid nor fussy. It breathes. He lets the red chalk wander at the calf, flutter at the beard, and tighten around the knee and elbow. Where the form turns away, the line thins and allows the wash to take over; where it approaches, the line thickens and warms. This responsiveness makes the body feel alive, not merely bounded. In places he doubles a contour, letting two related lines vibrate, which introduces a sense of movement even in repose. The line is not a fence; it is a pulse, and Pan’s body is the visible measure of that pulse.

The Pelt, the Tail, and Rustic Splendors

The pelt under Pan’s head is more than a pillow. Its shaggy edge frames the face and beard, creating a kind of rustic aureole that sanctifies sleep. The tail, meanwhile, curls with comic delicacy, its flick a reminder that the beast in Pan is gentle for now. Rubens relishes these rustic details because they allow varied textures: the downy pelt rendered with soft, thready strokes; the tail with a sinewy contour; and the clustered grapes with small, round thumbprints of color. Each texture answers flesh, making the god at once integrated with and distinguished from his pastoral world.

A Pastoral Without Landscape

Although vines and grapes appear, the sheet eschews a full landscape. There is no distant hill or stream—only the immediate floor of earth and the canopy of tendrils. This closeness intensifies the mood. Pan is not a tiny staffage figure lost in a panorama; he is the world for the moment of our looking. Everything we need to understand pastoral—a god of nature, the signs of harvest, the aftermath of music—is present within arm’s reach. Rubens thereby focuses attention on the human scale of myth: contact, texture, breath, and the bodily arc of rest.

Classicism Reimagined Through Flesh

Early seventeenth-century classicism often idealized bodies into polished coolness. Rubens keeps the grandeur but restores temperature. Pan’s torso has the weight and planar clarity of antique relief, yet its surface is warm and freckled with life. The relaxed abdomen refuses the cold perfection of sculpture, insisting on the truth of fatigue. By making classicism breathe, he reclaims antiquity not as remote authority but as a living source. “Pan Reclining” thus stands as a programmatic statement for Rubens’s art: the past must be felt through the senses to remain potent.

The Collector’s Picture and the Culture of the Studio

Sheets like this circulated among connoisseurs who prized the immediacy of the artist’s hand. They also served as studio resources—images of a type that could be recombined in paintings of bacchanals, nymphs, and satyrs. Pan’s reclining pose, with its hinge at the hip and ferrying arm, reappears in later feasts and revels by Rubens and his circle. The drawing therefore sits at the junction of private delight and professional practice: a finished sensuous object that doubles as a reservoir of forms. Its survival suggests that either Rubens or an early collector esteemed it beyond mere preparatory status.

Erotic Candor and Pastoral Ethics

“Pan Reclining” wears eroticism with candor but without vulgarity. The heavy torso, the softened abdomen, the goat thighs—all speak to fertility and appetite. Yet the sheet refuses prurience. The erotic resides in the ripeness of color and curve, in the suggestion of a nap after love or dance, not in explicit narration. In pastoral ethics the erotic is a natural good that needs proportion; Pan’s rest implies that measure has been found, at least for the afternoon. Rubens’s image treats sensual pleasure as a mode of harmony with the world, not as transgression.

The Face and the Tenderness of Fatigue

Rubens lingers over Pan’s face with a tenderness unusual for a being often caricatured. The brow relaxes but does not slacken; the eyelids close with weight; the beard fans outward like a slow tide. The features retain strength even in sleep. A faint crease between brows and the set of the mouth suggest a life accustomed to laughter and effort. This humane attention prevents the god from drifting into allegory alone. He is a person with a day behind him and a dream upon him, and that personhood is what makes the sheet so moving.

Time of Day and the Temperature of Color

The temperature of Rubens’s palette implies late afternoon. Warm light saturates the body; shadows are not blue-black but rosy umber; the air behind cools to a modest olive. Grapes pick up a low sun’s richer red. Even the paper’s natural tone becomes part of the hour, like dust glowing in angled light. Such temporal specificity strengthens the pastoral idea: it is not a generalized Arcadia but a particular hour when work and play culminate in repose. The god of noon idleness here belongs to a golden four o’clock.

Influence and Afterglow

Rubens’s ability to make a reclining male nude feel both antique and immediate would be crucial for later Baroque painters and draftsmen. The sheet’s warm-chalk manner, animated by washes and bodycolor, echoes through the work of Van Dyck and Jordaens and much later, in the eighteenth century, in the color-chalk bravura of Boucher’s studio. But Rubens’s Pan remains distinctive because it fuses musculature with atmosphere so thoroughly that one is unsure whether the glow comes from pigment or from the creature’s own warmth.

Conclusion

“Pan Reclining” is a compact manifesto for Rubens’s art: classical form quickened by color, myth made palpable through flesh, and drawing turned into a sensuous, complete world. The god sleeps with pipes in hand, vines wandering above and grapes at his hoof; the paper shines with heat as if the afternoon itself were trapped beneath the wash. In a year when Rubens was defining his mature voice in Antwerp, this sheet speaks fluently: pleasure is serious; myth is human; and beauty is a matter of breath, touch, and time as much as of line. To stand before it is to feel the pastoral hour settle—music spent, wine warm in the veins, and the earth a pillow.