Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: A Circle of Conversation Beneath a Single Trunk

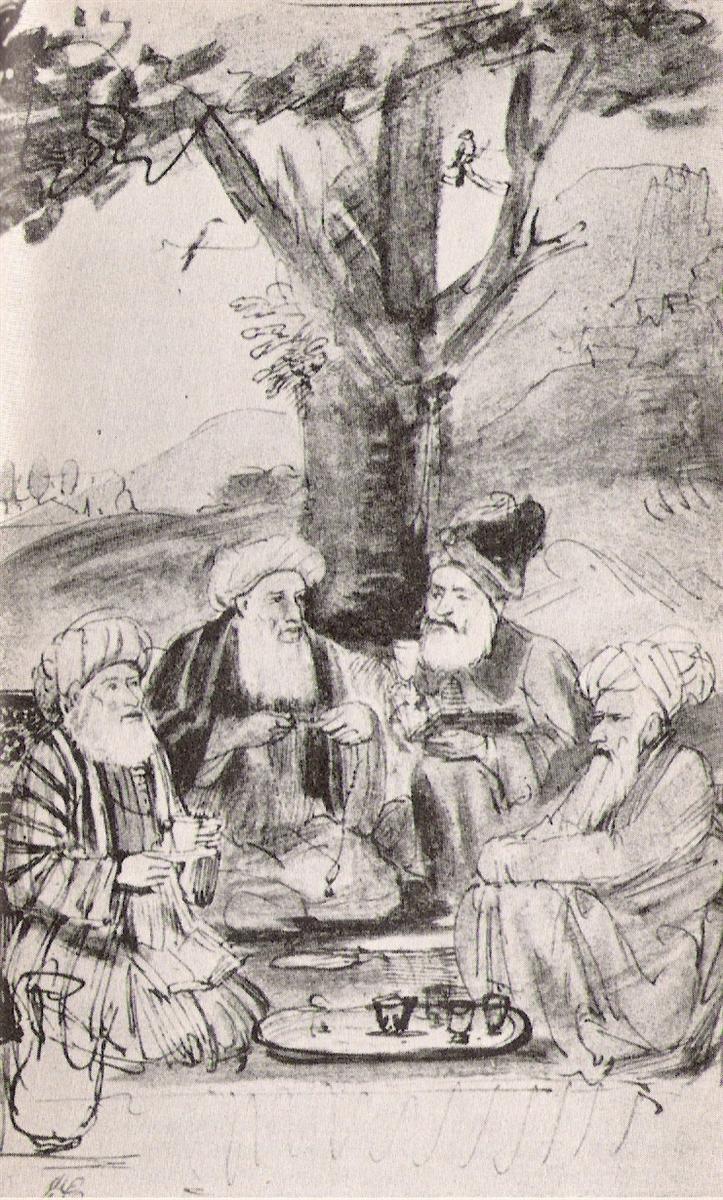

Rembrandt’s “Four Orientals seated under a tree” (1661) is a late drawing that turns a casual encounter into a meditation on looking, trade, costume, and fellowship. With a few charged strokes of pen and brush, he gathers four turbaned elders in a shaded circle at the base of a sturdy tree. Trays with small cups lie on the ground, a sliver of landscape opens behind them, and the page retains trials, corrections, and doodled lines that reveal the drawing’s improvisatory birth. Although modest in scale and made with simple means—brown ink and wash on paper—the sheet is as theatrically composed as a painting. The trunk anchors the scene like a stage prop; the patterned robes and beards hold the light; and the tilted heads choreograph an invisible conversation. The whole effect is intimate, humane, and worldly.

Amsterdam and the Allure of the “Orient” in Rembrandt’s Late Years

By 1661 Amsterdam was a port where continents met. Goods, languages, and people from the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, Persia, and the Indian Ocean world circulated through its streets. Dutch collections were studded with “Oriental” textiles, weapons, and garments, and Rembrandt’s studio contained a trove of such props. He used them not only to dress biblical figures but to dignify contemporary sitters, folding global fabrics into his art without turning people into curiosities. The sheet belongs to this cosmopolitan practice. Rather than staging conquest or exotic spectacle, Rembrandt sketches a pause: four elders at rest, sharing drink and talk outdoors. The subject is less “the East” as fantasy and more neighborly otherness—men who look different from the Dutch burghers yet are observed with the same respect the artist brings to scholars and apostles.

Materials and Method: Pen, Wash, and the Breath of Paper

The drawing displays Rembrandt’s late mastery of pen and wash. He blocks the main forms with a supple pen line that alternates between wiry speed and plush calligraphy. Over these lines he lays diluted washes to anchor shadows and give the scene weight. The wash is pulled lighter or darker with quick additions of water, creating a tonal weather that makes the figures feel grounded under a living canopy. Reserve—the white of the paper itself—serves as a luminous negative that defines cups, noses, and the sheen on patterned cloth. One can sense the order of operations: trunk first to stake the stage, then turbans and faces, then robe masses, trays, and finally the soft horizon. At the bottom edge, looping tests of the pen remain visible, charming evidence that he sharpened and restarted his instrument mid-thought rather than hiding the craft.

Composition: The Tree as Axis, the Men as Compass Points

Compositionally, the sheet is exact. The single tree rises through the middle third, splitting at shoulder height into broad limbs that fan across the upper register. Below this organic column, the four men occupy a low semicircle. Their differing heights and headgear set an easy rhythm: tall cap, wrapped turban, high turban, bowed turban. Each turns toward the center in a slightly different degree, so the eye is pulled around the group in a clockwise loop. The trays on the ground create a secondary ellipse that mirrors the group’s seating plan and steadies the page. Because the trunk is nearly vertical, Rembrandt can afford to keep the figures loose; the tree’s rectitude absorbs any pictorial wobble. It also supplies a symbolic touch—the gathering’s unity is rooted, not accidental.

Gesture and Expression: A Quartet of Types

Rembrandt individualizes the sitters with minimal means. The figure at left kneels with a cup held in both hands, the pen describing the stripes of his robe with alternating dark and light to suggest a fine weave. He reads as careful, perhaps ceremonial. The second figure, seated cross-legged in front of the trunk, leans forward with a slight protrusion of the cup—a host’s offering or the emphasis of a point made. His beard is lifted, his attention intent; a line under the lower eyelid convinces us he is older and alert. The third figure, wearing a high, pointed cap, angles toward the group while balancing a tray. His role feels practical, a facilitator who brings what the conversation needs. The fourth, at far right, sits back with elbows on knees, hands folded, head lowered under a wide turban. He listens. Without caricature, the four make a quartet: ceremonialist, speaker, server, contemplative.

Costume and Texture: The Intelligence of Line

The pleasure of the sheet lies partly in how line thinks through cloth. Turbans are articulated with spirals, scallops, and feathered strokes that imply layers of textile without pedantic description. Robes receive different treatments: the left figure’s striped garment is a ladder of vertical bands; the central figure’s cloak gains weight from densely nested hatch; the right figure’s outer cloth is a few long washes with pen accents at folds. This variety is not merely decorative. It individuates the men and reflects Amsterdam’s appetite for imported fabrics—silks, cottons, brocades—that were understood as carriers of status and story. Rembrandt’s mixture of precise stripes and loose washes also mirrors his approach to identity: some things are crisply known; others are suggested and left generous.

Light, Space, and the Outdoor Room

Though executed with a handful of values, the drawing creates convincing space. The canopy’s wash is darkest just above the men’s heads, functioning like a tent of shade that frames the luminous faces and beards. Behind the trunk, a lighter sweep of wash recedes toward distant hills, defined with minimal, lyrical lines. The ground plane is articulated by the trays and by the way robes settle into soft triangles at the knees. There is no theatrical chiaroscuro; instead, daylight spreads and gathers in pools. The scene becomes an “outdoor room”—private yet porous, enclosed by tree and hill rather than walls, the right kind of setting for shared counsel.

Hospitality and the Small Drama of Cups

Two circular trays with tiny cups punctuate the foreground. They are deliberately small, forcing the viewer to lean in and register the mundane details that make community: serving, receiving, sipping. Whether the drink is coffee, tea, or sherbet matters less than the ritual itself. Rembrandt’s world had only recently encountered coffeehouses and the social forms they fostered. Here, the cups become a grammar of hospitality—objects that move between hands and mark turns in a conversation. The left figure’s two-handed hold implies respect; the central figure’s forward cup projects a thought; the server’s tray supports the group; the contemplative keeps his hands to himself, at least for now. The drama is quiet and completely legible.

The “Oriental” Motif and Rembrandt’s Ethics of Attention

Seventeenth-century Dutch art trafficked in “Oriental” motifs that could slide easily into stereotype. Rembrandt’s drawings repeatedly refuse this simplification. He uses exoticizing costume to expand the visual vocabulary of dignity, not to flatten difference. The elders’ faces are modeled with the same gravity and individuality he gives to biblical patriarchs, apostles, or Amsterdam rabbis. The turbans do not serve as masks; they frame persons. Even the landscape avoids fantasy; the hills are plausible, the tree is Dutch, and the air belongs to the lowlands. The result is a meeting of worlds rendered without condescension—a sheet that acknowledges distance but insists on kinship through shared human acts.

Drawing as Thinking: Corrections, Trials, and the Speed of Insight

The lower margin preserves some of Rembrandt’s restless tests—loops and zigzags where the nib was tried, lines that start and stop around the trays, a few exploratory strokes on the ground. Far from diminishing the work, these marks reveal what the finished outline conceals: drawing as thought in motion. One can almost reconstruct the sequence of decisions: a quick lay-in of the trunk; a search for the right tilt of each turban; a test of how dark the canopy must be to hold the faces; a last-minute strengthening of the tray’s ellipse so the foreground would not drift. The drawing is not a copy of a finished idea; it is the event of an idea arriving.

The Tree as Metaphor: Shelter, Law, and Learning

The towering trunk is more than backdrop. In Jewish and Islamic traditions, as well as in the Bible, the tree figures as a place of lawgiving, judgment, or teaching: Abraham’s oak, Deborah’s palm, the Prophet’s shade. Rembrandt, a connoisseur of scriptural scenes, surely knew such associations. Whether or not he intended a specific citation, the effect is the same: the group reads as a council of elders under a natural canopy, wisdom gathering in shade. The trunk’s solidity contrasts with the fluid talk below; wisdom is rooted, conversation is alive.

Sound and Silence: How the Drawing Hears

Though silent, the sheet conjures sound. The central speaker’s mouth seems poised in mid-sentence; the server’s cups may clink; the kneeling elder’s stripes rustle as he adjusts posture; distant birds sketched in the canopy offer a thin, high register. Rembrandt’s penchant for narrative economy—telling as much as necessary and no more—invites the viewer to supply the rest. It is a cinematic still from an unwritten scene, and the viewer steps into the role of witness.

Placement Within Rembrandt’s Late Oeuvre

This drawing sits comfortably among Rembrandt’s late studies of scholars, travelers, and “Orientals” in conversation. Compared to his earlier, tighter pen work, the 1660s drawings breathe more. Wash takes on a larger role, line carries more personality, and the white of the paper is treated as an active light rather than blankness. The mood is consistent with late paintings such as the apostle portraits: spectacle reduced, presence increased. The sheet also dialogues with his etched “Three Trees” and other arboreal scenes, where a single trunk articulates weather and world. Here the tree becomes social architecture.

The Viewer’s Distance and the Ethics of Looking

We observe from the edge of the circle, neither above nor inside. The scale of cups, hands, and faces establishes a respectful distance—close enough to recognize expressions, far enough to avoid eavesdropping’s intrusiveness. The drawing thereby educates the viewer’s own attention. It suggests that to see well is to allow space. In this way the sheet participates in Rembrandt’s broader ethic: attention as a form of care.

Why This Small Sheet Endures

The drawing endures because it carries more human truth than its means would seem to allow. With ink, water, and paper, Rembrandt records rest, talk, service, and listening—four social acts that outlast empires and trade routes. The sheet is worldly without cynicism, spiritual without piety, and crafted without fuss. Its strength lies in how completely it trusts simple things: a trunk, four people, cups, shadows. That trust, like the tree itself, holds.