Image source: wikiart.org

A Ribbon of Land Beneath an Immense Sky

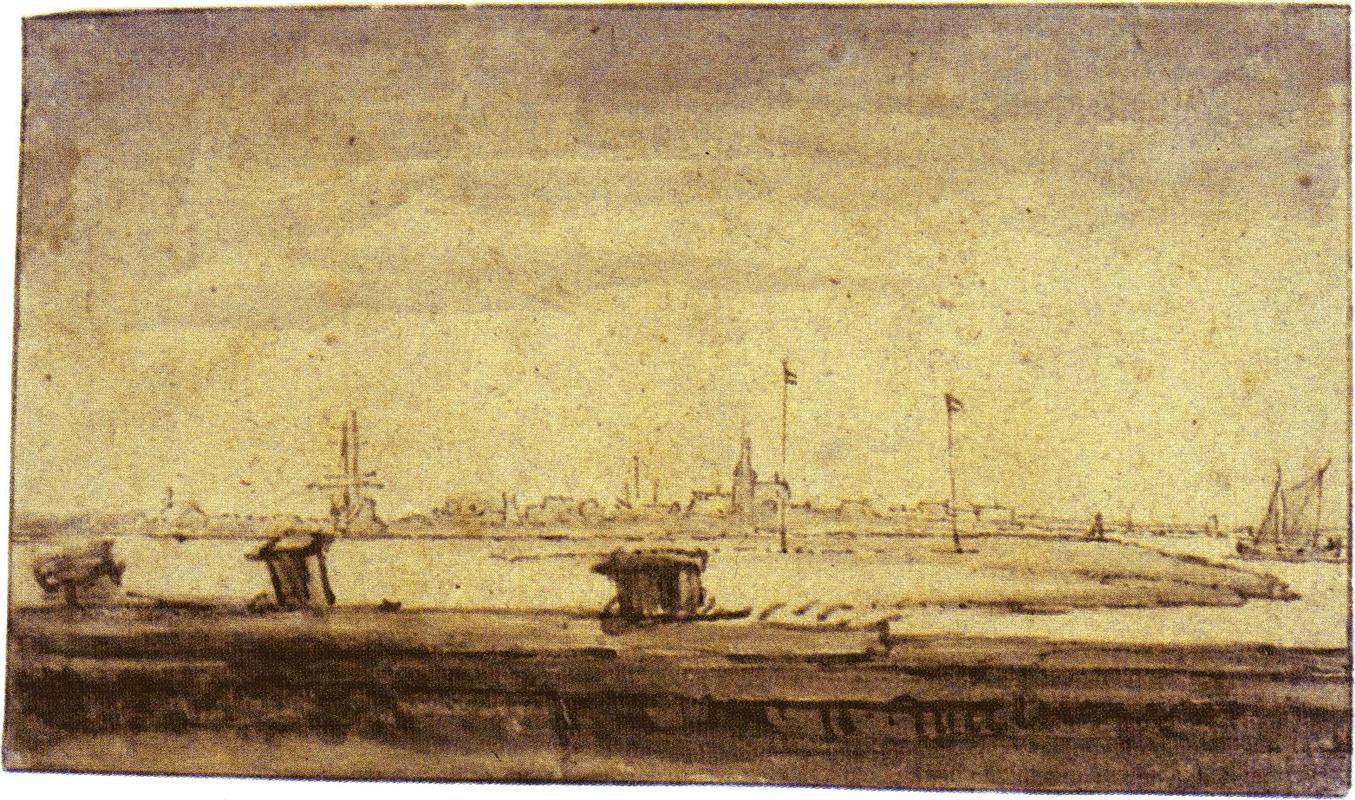

“Schellingwou seen from the Diemerdijk” presents the village of Schellingwoude as a thin, trembling line between water and heaven. Rembrandt spreads the world as a horizontal strip of life—masts, spires, flagpoles, and low roofs—while everything above is sky, a pale, breathing field of light. The sensation is of arriving on the Diemerdijk and pausing, as if one foot were still in the city and the other already in the quiet of the polder. The drawing’s modest means—pen, brown wash, and the paper’s warm tone—hold a landscape that feels wide, airy, and true to the Dutch eye.

A Panorama Built on Reserve

The format is startlingly panoramic for such a small sheet. Rembrandt lifts the horizon so that the village marches across the middle band, then allows the sky to teem with quiet gradations. The foreground is a low dark shelf of dike—planks, posts, and mooring bits—whose rough weight counterbalances the delicate distance beyond. This reserve generates amplitude. Because so much is left open, each mark matters, and a few accents conjure miles. The viewer scans from left to right as the features of Schellingwoude accumulate and dissolve like memories.

Diemerdijk as Stage and Threshold

The dike is more than a vantage point; it is the drawing’s stage and the region’s infrastructure. The Netherlands is a negotiated geography, and the Diemerdijk is one of its signatures, a place where land and water arrive at truce. Rembrandt renders the top edge of the dike as a dark bar, interrupted by mooring posts and small hut-like boxes. That heavy strip functions as the step on which we stand, reminding us that the view is made possible by labor—piling, tamping, dredging, and maintaining. By acknowledging the dike so frankly, the drawing gives civic work pride of place.

The Village as a Line of Signs

Rather than describe every house, Rembrandt writes the village as a sequence of signs: the windmill’s angled arms, the church spire’s needle, the flagpoles’ verticals quivering in the breeze. These strokes are reduced but intelligible; they persuade because they carry the rhythm of things seen often and well. The buildings are pressed into a continuous silhouette, yet this continuity refuses monotony because the silhouettes vary—low barn, taller gable, thin chimney. The village reads like handwriting across the horizon, legible to anyone who knows the low country.

The Generous, Luminous Sky

The sky sustains the drawing. Washes sweep horizontally, cooling slightly as they rise, leaving thin belts of light that behave as high clouds. There is no theatrical sunbeam, only a broad, breathable tone. The paper’s warmth shines through and becomes weather, a clear day with enough haze to soften edges at distance. Rembrandt trusts the sheet’s own color to do much of the atmospheric work, a technique that keeps the landscape feeling unforced, as if the sky belonged to the paper before the ink did.

Water as Quiet Motion

The stretch of water between dike and village bears the day’s calm. A few faint strokes suggest ripples and channels; the long, pale band feels weightless compared to the darker dike in front. Small boats register at the far right as triangles and stems, delicately entering and leaving the frame. Because water is so lightly handled, it behaves like time flowing through the drawing. The eye crosses it without resistance, lingering briefly on reflections implied rather than shown.

Economy of Means and the Virtuosity of Omission

The sheet is a lesson in how little is needed to evoke a place. A dot becomes a person; two slanted marks a boat; a thin notch a masthead pennant. What Rembrandt omits is as important as what he records. He withholds detail in the village so that the sky can breathe; he reduces foreground carpentry to dark blocks so they can carry structural weight without stealing attention. This virtuosity of omission makes the drawing feel swift but not careless. It reads as an exact memory rather than a catalogue.

Spatial Logic Without Rhetoric

Depth is achieved through simple, precise contrasts. The dike in front is the darkest zone, the water pale, the far shore slightly darker again, and the sky a field of stepped tones. Overlapping planes do the rest: posts against water, masts against sky, the spire pricking the horizon. There is no orthogonal framework or overt perspective construction. Space convinces because the tones are relational and the placement of accents is judicious. The world opens by degrees, the way it does from a real shore.

The Human Scale Hidden in Infrastructure

Figures are barely present but implied everywhere—in the tilt of a flag that requires someone to raise it, in the windmill waiting for wind and miller, in the boats that must be crewed. Even the anonymous kit in the foreground—bollards, skids, timber—speaks of hands. This indirect humanism is typical of Rembrandt’s landscapes. He preferred to let infrastructure and habit stand in for portraiture, suggesting communities by what they build and maintain rather than by individuated faces.

Weather, Season, and the Hour

The drawing feels like a bright, temperate day with a gentle breeze. Flags are upright; sails are furled or distant; shadow is scant. It could be late morning when the air has warmed but not yet shimmered. The season is ambiguous but likely spring or summer; the banks read dry and the sky lifts high. Rembrandt rarely forces meteorology. He lets mild weather be the common mood of workdays, the usual climate of looking, which gives the scene an everyday honesty.

A Conversation with Dutch Landscape Traditions

Seventeenth-century Dutch landscape characteristically places a low horizon beneath great reaches of sky. Rembrandt embraces that convention yet personalizes it with his handwriting. Compared with the finish of Jacob van Ruisdael or the glassy stillness of Jan van Goyen, this sheet is freer, more impulsive. It belongs to the family of outdoor studies that fed Rembrandt’s larger etchings and paintings, but it also stands as a complete thought: a note from the world taken at the speed of walking.

The Foreground as Counterweight and Frame

The dike’s dark shelf creates a counterweight that prevents the pale middle distance from floating away. Its rough rectangles behave like a low proscenium, framing the spectacle of village and water beyond. The eye keeps returning to these humble forms—mooring posts, small sheds, staved barrels—because they anchor us in our position as spectators. The world we watch is both near and far, and the foreground objects remind us we occupy a place among things.

Drawing as Thinking

The tremor of certain lines, the adjustments in wash density, the slight revising contours around the windmill all testify that the sheet records thought in flight. Rembrandt draws like a person who wants to understand how the place holds together—where the dike drops, where the flagpoles interrupt, where the river forks. The sketch is an instrument of comprehension rather than a rehearsal for show. Its authority comes from the clarity of a mind mapping a view it loves.

The Ethics of Attention

What seems casual is, in fact, a moral attitude. Rembrandt’s landscapes offer respect to the ordinary—dike, ditch, boat, and church—without hierarchy. The church spire punctuates the skyline, but no divine glare sets it apart from windmill or flag. The drawing honors the civic fabric that sustains a community: water management, transport, industry, worship, and daily passage. By giving each element its measured sign, Rembrandt celebrates a society of parts in equilibrium.

Memory, Geography, and the Artist’s Walks

The area east of Amsterdam—the Amstel, the Omval, the Diemerdijk—was Rembrandt’s habitual walking ground. The smallness of his notation suggests routes traveled often, where one glance suffices to recall the whole. Schellingwoude’s skyline would have been as familiar to him as a friend’s profile. This intimacy explains the drawing’s confidence: it is less a discovery than a recognition, the moment when a trusted view meets a ready hand.

The Panoramic Impulse and Cinematic Anticipations

The sheet anticipates the cinematic establishing shot: a long lateral band of world in which a town situates itself. Our eye moves like a camera along the horizon, counting features and calibrating distances. The dark bracket of the dike in the foreground functions like a dolly track, a reminder that we could slide left or right to discover more. This sense of motion within stillness keeps the drawing alive; it feels like a moment seized from ongoing transit.

The Paper as Weathered Surface

Specks, stains, and the tooth of the paper show through the washes, creating a subtly mottled atmosphere. These material accidents are not flaws; they are weather. Rembrandt allows the sheet to collaborate, its texture giving grain to sky and water. The drawing thus records two histories at once: the history of a Dutch view and the history of a piece of paper absorbing ink, aging, and catching light.

A Poetics of Small Distances

The most touching passages are the tiniest: a single dab for a flag catching wind, a pinprick for a distant masthead, a faint rise of wash where the bank swells. These small distances register the scale at which Dutch life was lived—across polders and canals where far and near are compressed by level land. The drawing’s poetics depend on this compression. It makes a country feel intimate without denying its breadth.

Comparisons Within Rembrandt’s Landscape Sheets

Placed beside Rembrandt’s panoramic “View of Diemen” or his sketches along the Amstel, this sheet shares the same grammar of thin horizons and generous sky. Yet each view has its own temperament. Here the presence of flagpoles and the stout church mass lend a slightly ceremonial air, as if the village were quietly self-aware of being seen from the water. The darker, more assertive foreground also distinguishes this sheet, giving it the feeling of being taken from a working edge rather than a meadow path.

Why the Image Endures

The drawing endures because it captures a relationship between people and place that has not grown old. It speaks of maintenance, travel, worship, trade, and watching the weather. It values the surface of things without demanding spectacle. Its horizon reads like a sentence in which every noun is necessary and no adjective is wasted. We return to it not for drama but for equilibrium, the calm of forms placed exactly where they belong.

A Quiet Masterclass in Seeing

Ultimately, “Schellingwou seen from the Diemerdijk” is a masterclass in seeing with restraint. The dike’s weight, the water’s pale glide, the thin skyline and generous sky—all conspire to make a whole more convincing than its parts suggest. It is a drawing that trusts viewers to finish it in their own eyes, supplying the shimmer of the water and the sound of distant sails. In its modesty lies its radiance, and in its brevity, a long, steady breath of the Dutch world.