Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

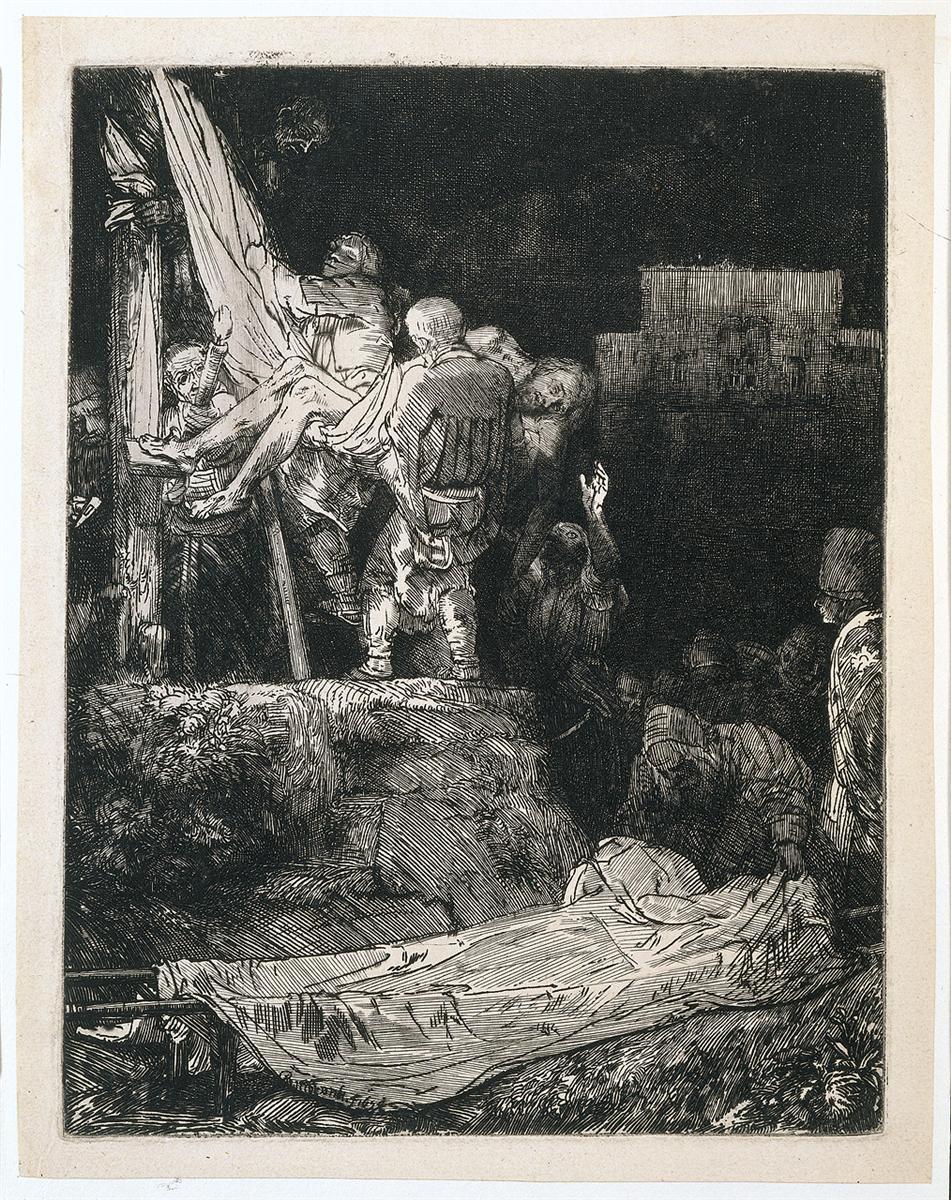

Rembrandt’s “The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight” (1654) is a night scene that turns a familiar Gospel subject into a study of labor, light, and grief. Working in etching with drypoint accents, Rembrandt compresses the drama into a steep, vertical stage where the dead Christ is lowered from the cross while a torch flares somewhere out of frame. The upper half of the plate is a pool of darkness against which figures burn like embers; the lower half opens into a wide ledge where a shroud waits, already lit and spread, as if it were a page prepared for writing. The print is both narrative and meditation, an account of hands doing necessary work and an image of how light behaves when love meets death.

The Gospel Moment and Rembrandt’s Choice of Night

All four Gospels describe Jesus being taken down from the cross by followers who receive permission to bury him before the Sabbath. Artists often set the event at twilight, suffusing the sky with theatrical glow. Rembrandt chooses a later hour and a harsher source: torchlight. Night changes everything. It turns the operation into a craft problem—how to lower a body safely from a height—and it forces light to become meaning rather than atmosphere. Torchlight cannot bathe a scene; it strikes and withdraws, leaving forms to appear and then dissolve. The choice aligns with Rembrandt’s late interest in work done in the margins of public life and in how small brightnesses find their way through large darkness.

Composition as a Steep Theater

The composition is organized as a high, vertical wedge of action that plunges toward a horizontal spread of cloth. At the upper left, the cross stands as a timbered mast; a ladder leans against it, its rungs etched with calligraphic speed. Behind and below the cross a knot of figures strain to manage the weight of the body. One man stands on the ladder, guiding a sheet that functions as sling; two others, backs turned, receive and lower; a fourth crouches to support the legs. Slightly apart, a figure raises a hand in a gesture that reads as both practical signal and blessing. The right side is a mass of mourners and helpers submerged in shadow. At the very front, a shroud lies across a bier or ground, illuminated in a broad wedge. This arrangement creates a visual sentence: labor above, reception below. The eye travels from the effort of descent to the quiet plane that will receive the work’s result.

Torchlight and the Poetics of Shadow

The print explores what torchlight does to space. It creates hard-edged planes of brightness, leaves gulfs of blank dark, and carves faces into relief only where they turn toward the flame. Rembrandt exploits this optical regime with mastery. The cloth that slings the body flashes pale against the cross; the bald back of the central bearer gleams like a polished stone; Christ’s torso and thigh catch light in islands that drift within the sea of black. In the right background the city walls of Jerusalem are rendered as a dense grid of hatchings, a rectangular ghost barely surviving the night—a world that persists but no longer commands the scene. The flame’s rule feels moral as well as optical. It says that in grief, attention becomes selective and merciful; we see only what we need in order to act.

The Body as Weight and Tenderness

Few artists have been as persuasive about the weight of a body. Rembrandt etches Christ’s form with an economy that nonetheless communicates gravity: the head slack, the abdomen soft, the knees bent by the lift. The men lowering him are not anonymous props; their postures show the strain of coordinated effort—backs rounded, feet braced, arms threaded through cloth. There is no grand gesture of display, no theatrical unveiling for the viewer’s benefit. The choreography is about safety and care. The sling is practical, the descent controlled, the hands mindful. Rembrandt insists that love is a kind of competence.

The Shroud as an Empty Sentence

The most radical invention in the print is the bright, empty shroud stretched across the lower foreground. It occupies a third of the plate, gleaming with unmodulated whites and a few folding lines. In narrative terms it is the destination. In pictorial terms it is a field of expectation, a place where the next line of the story will be written by the body’s arrival. Positioned so close to the viewer, the shroud converts us from spectators into assistants. We are placed at the edge of the cloth with open hands, ready to receive the weight that is coming. The device is both formal and devotional—a perspectival invitation to nearness and a moral request for participation.

The Crowd and the Ethics of the Margin

Unlike some of Rembrandt’s earlier Passion scenes filled with cavalry and taunting onlookers, this gathering is inward and purposeful. Figures at the right crouch, confer, or bow; an older woman stoops as if to arrange linens; a man bends to tie or steady a rope. Their anonymity is essential. The group is a community of helpers whose names history does not record. By pushing them into darkness Rembrandt dignifies them without turning them into portraits. The ethics is clear: the important people at this hour are those who know what to do and do it quietly.

Architecture, Ground, and the Sense of Place

Rembrandt provides just enough environment to anchor the work. The cross is sunk into a rough ledge, etched with tight, wiry strokes that feel like cut stone. Low vegetation curls at the brink. Far back, the city’s blocky silhouette rises like a sleeping bulk. The night is a sky of unworked plate, printing as velvety black. These elements suggest a world that continues beyond the torch’s reach, reassuring the eye that this small illuminated theater sits within a larger geography and history. But all essential action happens at the cliff’s edge and at the foreplane where the cloth glows.

Line, Plate Tone, and the Tactility of Night

This is a plate made by a hand that trusts what line can do. Rembrandt uses long, parallel runs to compact large shadows; zigzag strokes to energize fabric; small drypoint burrs to roughen edges and thicken darkness. He leaves plate tone in the upper field so the sky prints as respirating black rather than dead void. Faces are not modeled by crosshatched diagrams but by a handful of directing strokes placed where torchlight would land: a highlight on a cheek, a sudden curve at a brow, a nick of white at a tooth. The technique’s restraint enhances the sense of being present; the scene does not feel drawn so much as encountered.

Gesture, Sign, and the Language of Hands

Hands speak everywhere. The man on the ladder grips the sling with one hand while extending the other to steady; the bearer beneath forms a shelf with his forearms; a figure to the right throws up a palm—a signal to lower more slowly, a prayer, or both; in the shadows several hands knot cloth, pull rope, or press against rock. The variety of handwork underscores the communal nature of the rite. Removing a body from a cross is dangerous and heavy. It requires coordination and trust. Rembrandt turns those requirements into a visual theology: community is how love manages weight.

Night as Theology

Night is not merely atmospheric decoration; it sets the spiritual temperature. In darkness, spectacle disappears and action becomes local. The torch makes a cone of necessity within which people must think with their hands. The world recedes to silhouettes; what remains is the task. Rembrandt’s night thus becomes a theology of the in-between: the gap between Crucifixion and Entombment, between loss and what must be done next, between public violence and private care. The print dwells in that interval where meaning is carried by work.

Dialogue with Earlier Descents

Rembrandt had painted a grand “Descent from the Cross” as early as 1633, a brilliant, altarpiece-like composition with theatrical light and rich color. The 1654 etching remembers that staging but strips it for parts. The ladder remains, the diagonal descent persists, and the coordinated figures still perform their solemn skill. Yet everything has tightened. The paper’s blacks replace the painted sky; the shroud now occupies the viewer’s space; and the crowd is smaller, more concentrated. The change is not a renunciation of drama but a refinement—less pageant, more proximate truth. The late style replaces radiance with density.

The Role of Women and the Breath of Lament

Though the print privileges labor, a minor key of lament runs through it. A woman near the cross’s foot raises an arm, her gesture wavering between reaching and mourning. Another figure at the far right bends as though overcome or busy with some necessary preparation. Rembrandt refuses to isolate grief from work; he interlaces them. Tears do not postpone labor; labor does not silence tears. The torch’s light finds both and allows them to coexist.

The Viewer’s Vantage and the Invitation to Help

The perspective places the viewer at ledge-level, close to the shroud. This is not the viewpoint of an audience seated in an amphitheater; it is the stance of a late-arriving helper whom the others trust. By refusing an elevated, central vantage Rembrandt gives the print its unusual intimacy. We are not privileged observers; we are implicated. The response the image asks for is not admiration but readiness.

Speed, Revision, and the Feeling of Event

Look long enough and you can see the artist’s hand rehearsing and correcting. Lines search along the crossbeam, then commit; hatches fill the sky, thicken, and stop; a face is suggested, then half-erased by a flood of tone. This visible process imparts a temporal quality to the scene. We feel the action as an event rather than a frozen monument. The medium bears witness to the moment in the same way the figures do.

Color Implied by Tonal Drama

Although the print is monochrome, Rembrandt implies color through value and texture. The sling’s pale field suggests linen; the rough tunics, etched with wiry lines, read as coarse earth hues; the city walls sink into a stony gray imagined from the crosshatching. The torch’s unseen flame registers as warmth on skin. Our eye fills in the chroma, making the scene oddly vivid in spite of its blackness. This is chiaroscuro as a generator of imagined color.

Time Suspended Between Tasks

The image halts the descent at a critical second—Christ’s legs just clear of the slanting beam, the shroud still empty but ready. That suspension gives the print its pressure. What we look at is about to change. Because the composition sets the shroud so close, the viewer anticipates the next action almost physically. The print becomes a hinge rather than a conclusion, a picture of transition given the dignity of focus.

A Contemporary Reading

Seen today, the image speaks beyond its devotional subject. It honors people who undertake skilled, unglamorous work at night—the nurses, attendants, undertakers, and volunteers who handle bodies with competence and care. It acknowledges that some of the most important things we do happen away from public eyes, in difficult light, with tools that are simple and hands that are sure. The picture’s morality is unpretentious: do what must be done together, and let light be where you need it most.

Conclusion

“The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight” is one of Rembrandt’s great meditations on care under pressure. In a field of black he carves a small theater where bodies cooperate to lower a beloved weight and where a bright, empty cloth waits to receive him. Torchlight gives the scene its grammar of revelation—sudden islands of brightness amid necessary dark—while the etching line gives it tactility and pace. The print replaces spectacle with nearness, rank with craft, and rhetoric with the eloquence of hands. Its power lies in the way it asks nothing beyond our attention and then turns that attention into a form of help.