Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

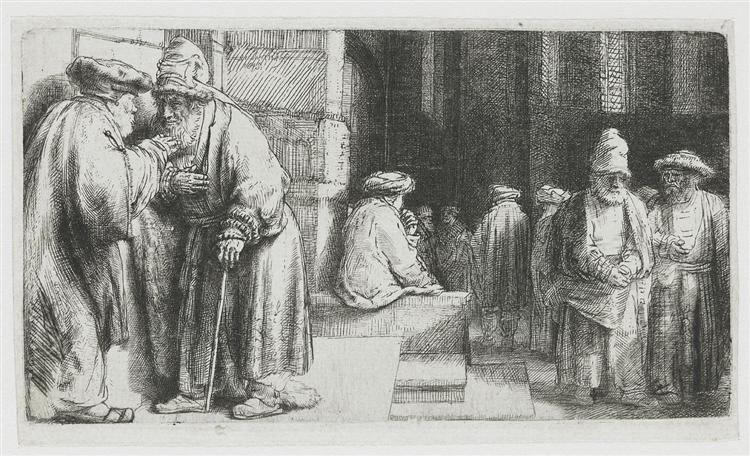

Rembrandt’s “Pharisees in the Temple (Jews in the Synagogue)” from 1648 is a compact but extraordinarily rich etching in which a community of men occupies a cool, stone interior. What might, at first glance, appear to be a casual study of congregants quickly reveals itself as a subtle meditation on rhetoric, listening, ritual, age, and the textures of civic religion. The plate gathers small dramas: a whispered exchange in the foreground, a seated figure pivoting to hear, and clusters of elders who fold their hands and drift into shadowed aisles. Rembrandt does not sermonize. He lets etching’s fine web of lines carry the hum of human presence, the hush of a sacred space, and the moral ambiguity of speech itself.

Historical Context and Subject

The subject is not a single biblical episode but a genre-like view of Jewish elders in a synagogue or temple precinct. In seventeenth-century Amsterdam, Jewish communities—Sephardic and Ashkenazic—were visible parts of urban life. Rembrandt lived among them, drew them, and hired Jewish neighbors as models. The term “Pharisees,” inherited from older Christian traditions, was often used loosely to denote learned Jewish elders; here it functions less as doctrinal polemic than as a recognizable label for religious scholars. Rembrandt’s etching, dated 1648, thus emerges at the intersection of curiosity, observation, and the artist’s ongoing commitment to portray people of diverse faiths with gravity and nuance.

Composition and the Choreography of Groups

The plate is organized as a triptych of social energies. At left, two men lean in close; the man in profile gestures emphatically while the other, stooped and staff-bearing, receives the words with guarded attention. At center, a seated figure occupies a stepped stone block; he twists to face the conversation while still anchored to his seat, becoming a hinge between foreground and the receding chamber. At right, a loose congregation of elders drifts into the dark nave, their forms layered in diminishing scale. Architectural piers divide the space, but Rembrandt places his primary verticals just off the plate’s thirds, so the eye never locks into symmetry. The steps in the middle ground guide our gaze inward, and the repeated motif of folded hands steadies the scene with a rhythm of stillness.

Architecture as Moral Weather

Rembrandt builds the setting from heavy stone, ashlar blocks, and high, brick-patterned walls. The interior is not described with architectural pedantry; rather, it is evoked with textures that feel cool and absorbing. The space functions as moral weather. Large planes of shadow along the right draw sound inward and dampen it; the sunless recesses suggest a place made for study and reflection. The broken rectangle of steps to the center-left invents a small stage on which the quiet drama of speech and listening unfolds. Architecture here is neither mere backdrop nor symbolic burden; it is the environment that shapes how people stand, approach, confer, and withdraw.

Chiaroscuro and the Direction of Attention

Light slips across the sheet from the left, casting the whisperers in relatively clear tones while leaving the right-hand group in a composed dusk. The seated listener is modeled with mid-tones, a transition that helps the viewer’s eye travel from bright foreground to dark assembly. Rembrandt’s mastery of plate tone—the thin film of ink left on the copper—produces soft veils in the nave and a dry clarity along the steps. The effect is cinematographic: light does not flatten; it edits. We are invited to pay earliest attention to the exchange at left, then to let our vision adjust to discover secondary scenes in the shadow.

Gesture, Posture, and Psychological Readability

The drama rests in gestures rather than faces. Hands press to chest, fold under sleeves, or tuck into drapery; heads angle to catch speech or to avoid it; feet plant or shuffle. The elderly figure with a staff draws his robe inward, a protective gesture that signals caution or humility. The whisperer’s hand, lifted and partially hidden, sharpens the sense of something confidential, persuasive, or even contentious. On the right, an elder inclines subtly toward his companion while keeping his hands closed, posture announcing reserve rather than engagement. These small physical attitudes give the scene its moral temperature—neither pandemonium nor rigid solemnity, but the hum of a debating community, with all the attendant rituals of assent and doubt.

Clothing, Rank, and Identity

Rembrandt lavishes attention on garments—layered cloaks, soft caps, and turban-like headgear. The clothing carries regional and communal identities without exoticizing them; it situates the figures in a specific, recognizable world. Ranks are legible through drapery scale and stance rather than badges: those with ample robes and covered heads cluster as elders; a younger figure at center, seated but alert, inhabits a more transitional status. The abundant fabric also serves a pictorial purpose, providing fields for cross-hatching that model volume and give weight to bodies moving through cool air.

The Sound of the Plate

Although we cannot hear the scene, the print breathes with implied sound. The thick hatchings in the nave seem to absorb voices into a murmur; the open bites around the figures at left let whispers ride more clearly. Rembrandt’s etched line is never merely descriptive. It captures the texture of speech: where lines are close and parallel, we sense secrecy; where they scatter and dig more deeply, we feel the gravel of older throats. The steps, rendered with broader strokes, ground the men’s sandals with a tactile scrape that echoes the slow shuffle of congregants who know the space by heart.

The Ethics of Looking

Views of Jewish life in Christian art often carry caricature or polemic. Rembrandt’s etching resists both. He neither ridicules nor flatters; he observes. The men are particularized—some stout, some slender, some bent with age, some upright—and placed within a structure that dignifies thought. By positioning the viewer at a respectful lateral distance, he allows us to witness without intruding. We stand as if just inside the doorway, our presence acknowledged by no one. The etching thus cultivates an ethics of looking: to watch attentively yet not presume mastery over what we see.

Technique, Line, and Tonal Engineering

The plate showcases a full vocabulary of etched marks. On the stone piers, long parallel strokes suggest masonry grain; in the robes, broken hatching and little chevrons express folds; in the darkest recesses, tighter nets of lines build a breathable black rather than a dead void. Edges are rarely hard; instead, they dissolve into the surrounding texture, allowing figures to sit naturally in space. Rembrandt’s control of drypoint-like burr in certain accents enriches shadows at sleeve and beard. The technical problem—how to balance intricate figure groups with massive architecture in a small rectangle—is solved by staggering densities of line so that the eye always finds a resting place before moving on.

Time, Suspense, and Narrative Possibilities

The etching does not tell a single story; it generates possibilities. What is being whispered? Are legal matters under discussion? A point of scriptural interpretation? A community dispute? By refusing to anchor the scene to a known episode, Rembrandt lets the print function as a template for many kinds of human exchange. The suspended moment leaves viewers free to project, but the carefully managed gestures keep speculation tethered to believable behavior. It is precisely because the scene could be many conversations that it feels faithful to the life of a synagogue, where interpretation and communal decision are ongoing, not episodic.

Comparisons within Rembrandt’s Work

Rembrandt repeatedly depicted groups of learned men—rabbis, scholars, and disciples in biblical scenes. Compared to the dramatic spotlighting of “Christ Preaching” or the theatrical organization of “The Hundred Guilder Print,” this 1648 plate is quieter and more democratic. There is no single protagonist around whom others orbit. Authority is dispersed among elders and founded on the habit of listening. The difference is not merely compositional; it reflects Rembrandt’s interest in communal intelligence, in how meaning is produced collectively in rooms dedicated to study.

Age, Memory, and the Texture of Wisdom

Age saturates the sheet: soft caps pulled low, hands that lean into the memory of staffs even when none are held, shoulders that curve like question marks, beards that thicken with the burr of the needle. Yet age is not treated as decline. It appears as a store of memory, a bodily archive of practice and prayer. The younger men who appear farther back inhabit a different rhythm—less weighty, more upright—but the etching stages them all in the same luminous dusk, as if to grant continuity across generations.

The Viewer’s Path Through Space

Rembrandt orchestrates a clear itinerary for the eye. We begin at the left foreground with the whisperers, where drawing is open and granular. We step inward along the ledge toward the seated pivot figure, whose turned head invites us to rotate with him. We then slip into the nave, where dense hatching slows us down, encouraging a lingering inventory of faces and postures before our vision dissolves into the patterned brick at the far right. That path is not merely optical; it is moral. It moves from talk, to listening, to community—a cycle that the space encourages us to repeat.

Print Culture, Multiplicity, and Audience

As an etching, the work existed in multiple impressions, each an original capable of traveling beyond Amsterdam to collectors and connoisseurs. This multiplicity matters. The subject—a religious minority in a Protestant city—could be contemplated in homes across Europe, not as curiosity but as a study of civic life. Rembrandt’s soft, humane gaze, carried by paper, had the potential to complicate stereotypes. The print thus functions both as an artwork and as a small engine of cultural encounter.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Today the plate speaks with renewed clarity. It images a community negotiating belief, law, and daily affairs within a shared structure—a theme that resonates wherever people gather to interpret texts and decide how to live together. It offers a model of representation that is neither voyeuristic nor abstract: bodies have weight, rooms have echo, conversations have consequence. And it confirms Rembrandt’s singular gift for turning the particular—a fold of cloth, a set of steps, a glance into shadow—into a universal language of attention.

Conclusion

“Pharisees in the Temple (Jews in the Synagogue)” is an etching of modest size and quiet tone, yet it contains a world. In a handful of figures and a stone interior, Rembrandt stages the essential human acts of speaking, listening, doubting, and belonging. He uses architecture to cradle discourse, light to guide conscience, and line to register the breath of a room where minds meet. The plate does not instruct us what to think about its subjects; it teaches us how to look at them—with patience, humility, and a respect for the slow labor of interpretation that binds a community together.