Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

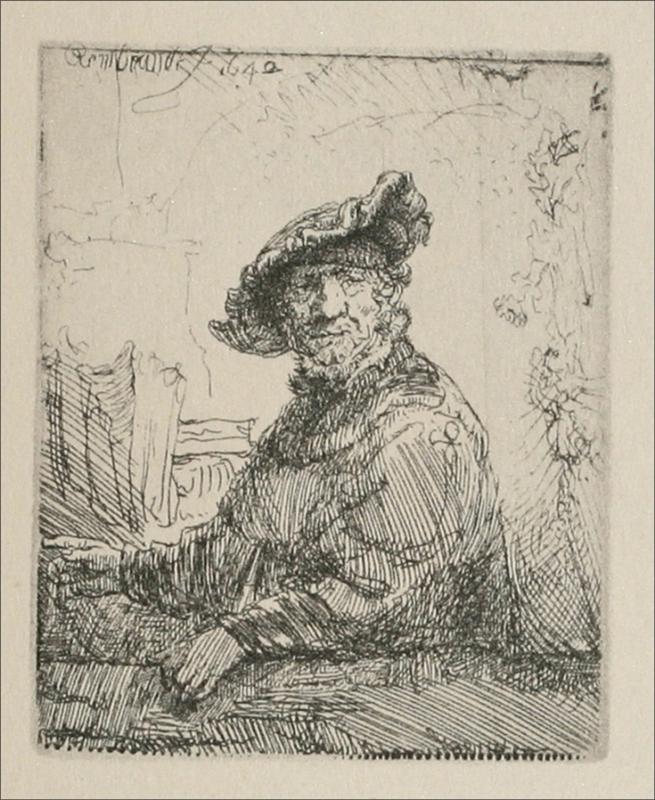

Rembrandt’s “A Man in an Arboug” (1642) is a small etching that opens onto a surprisingly capacious world of mood, character, and quiet summer air. A single seated figure, turned three-quarters toward us beneath a leafy bower, occupies the foreground like a friend just discovered in shade. The print’s scale is intimate, yet the visual sensation is generous: a curtain of foliage to the right, a slatted fence and perhaps a glimpse of field to the left, and the man’s softly lit face emerging from elastic networks of line. Rembrandt turns a simple pause in a garden into a concentrated study of how a human presence transforms space. The man’s hat is broad and soft, the coat ample; his hands rest with the weight of ease; his gaze, half alert and half contemplative, establishes a dialogue with the viewer that is both social and inward.

Subject and the Garden Setting

The title leads with location: the man sits in an arbor—an outdoor structure of trellis or intertwined branches that creates an architectural shade. Dutch gardens of the seventeenth century favored such small architectures: places to read, talk, eat, or simply cool the brow from the city’s glare. Rembrandt deftly models the arbor without over-drawing it. At the right, a loose lattice of leaves and tendrils signals living architecture; at the left, a vertical panel or fence slats imply enclosure and privacy. The figure’s chair and table are only hinted at by a few horizontal strokes, so that space stays airy. We are not trapped in a room; we are in a shelter open to breezes and conversation.

Composition and the Architecture of Ease

The figure is placed slightly off center, turned to the left so that his outstretched arm and relaxed hand trace a shallow diagonal across the foreground. That diagonal counterbalances the verticals of the fence and the tremulous uprights of foliage, giving the sheet a compositional rhythm of lean and lift. The hat’s wide oval echoes the curve of the shoulders; the rounded masses settle the image like stones in a shallow stream. Negative space—thin air left blank—gathers above the shoulder and around the head, admitting light while keeping the man the primary visual event. The result is a composition that feels unforced, as if caught in passing, yet carries the stability of a portrait.

The Etcher’s Line

Everything here is achieved with line—etched, bitten, and wiped. Rembrandt varies pressure and spacing to summon an orchestra of textures. The coat’s heavy cloth appears through tight, parallel hatching that swells and thins with the body’s volumes. The hat’s felt is a looser weave of marks, its crushed brim described by short, jostling curves. The face is handled with a sparer vocabulary: just enough contour and cross-shadow to locate bones, beard, and eye sockets; just enough reserve of paper to let light pool on cheek and nose. At the right, the arbor’s leaves devolve into energetic squiggles, the graphic equivalent of a rustling sound. The fence on the left receives straighter, carpenterly strokes, so that organic and made structures speak distinct dialects within the same language of ink.

Light and the Psychology of Shade

Rembrandt’s handling of light feels almost meteorological. The man’s face emerges from shadow but never blazes; it is lit the way one is lit under trees—broken highlights, soft transitions, an overall temperature of cool. The darkest blacks appear not in the face but in the layered clothing and the deep pockets of foliage, which has the effect of letting the features breathe. Garden shade becomes psychological shade: a condition of thoughtfulness rather than gloom. The white of the paper, carefully reserved in small fields on forehead, cheek, and fingers, reads as dispersed daylight filtering through leaves. The image captures not drama but weather in the mind.

Costume and Social Temperature

The sitter wears a voluminous, practical coat and a soft, broad hat. There is no courtly stiffness here, no armor of lace and starch. The garments suggest a person of modest means or modest mood—perhaps a craftsman at rest, a townsman who has stepped outdoors after work, or simply a model dressed by the artist. Rembrandt often treated clothing as moral weather: fabrics suggest not merely status but temperament. The softness of the hat and the forgiving folds of the coat make the man approachable. The impression is of someone who can settle into a bench and talk.

Gesture, Gaze, and the Human Exchange

What gives the print its lasting charm is the sitter’s expression. His eyes, shaded by the hat, glance outward with interest rather than challenge. The mouth is mobile, perhaps caught between words; the beard is briskly struck but full of character. The left hand rests on the table’s edge, fingers relaxed and slightly curled, an afterimage of conversation. The body’s turn implies hospitality—as if he has swiveled to include us in whatever topic was underway. Rembrandt consistently finds character in posture: here, the curve of the back and the anchored elbow suggest a person settled enough to be curious.

The Arbor as Threshold

An arbor is neither house nor open field. It is a threshold space, porous, green, and provisional. Rembrandt makes use of that ambiguity. The fence to the left declares a boundary; the foliage to the right invites the eye to wander. The sitter inhabits this in-between place with ease, as if the middle ground between privacy and sociability suits him. In Rembrandt’s world, thresholds are often where humanity shows best: doorways of inns, benches by canals, corners of rooms, arches of bridges. They are places where encounters happen and the self is tested gently by the presence of others.

Scale and Intimacy

The print is small, yet the sense of presence is large. Rembrandt achieves this paradox by focusing scale cues around the hand, the hat, and the mass of the torso, allowing the environment to remain suggestive. When we hold the sheet close, as the print expects, we find ourselves at conversational distance. The intimacy is not simply optical; it is ethical. The man is drawn with the respect one extends to a neighbor. His features are particular but not demonstrative; his mood is accessible. The viewer’s nearness completes the picture’s quiet social contract.

The Tronie Tradition and Portrait Ambiguity

Seventeenth-century Dutch artists produced tronies—studies of heads in costume, not necessarily portraits of specific people but explorations of character. “A Man in an Arboug” participates in that tradition while tilting toward portraiture. The specificity of features suggests a real sitter, yet the anonymity of the setting and the absence of cues such as a name or coat of arms keep identification open. This ambiguity allows the image to speak more broadly about human presence: it is a face and posture we recognize from life, not a public identity demanding ceremony.

Paper, Plate Tone, and the Variety of Impressions

As with many Rembrandt etchings, impressions can differ markedly. A light wiping of plate tone can leave a film of ink that enriches the arbor’s shadow and softens the sky, deepening the quiet. A cleaner wiping throws the face forward, increasing contrast. On slightly toned paper, the highlights mellow; on whiter sheets, the brim flashes more brightly. These variables are not incidental; they are part of the artist’s expressive vocabulary. He prints not just an image but a mood calibrated for each impression.

Sound and Atmosphere

Though silent, the print is filled with small noises one can almost hear: leaves shifting in a light wind, a distant cart on a lane beyond the fence, the quarter hour from a church bell, the man’s breath as he shapes a sentence. Rembrandt’s line encourages such auditory imagination by refusing to seal the world with outline. The foliage frays into the white field; the fence lines skip and pick up again; the hat’s brim is a soft, absorbent edge. Openness to sound is openness to others; the arbor becomes a small theater of listening.

Garden Culture and Dutch Domesticity

The Dutch Republic brought the garden close to everyday life. Urban houses had small yards; country plots were tended with pride; public walks were planted with trees. An arbor embodied a domestic ideal: shelter without walls, ornament without extravagance, comfort in proximity to growth. Rembrandt’s choice of this setting aligns the sitter with that civic, practical humanism—pleasure rooted in maintenance. The trellis suggests work done over seasons; the leaves imply the gardener’s hand as much as nature’s. The man in the print is both guest and keeper of this green architecture.

Comparisons to Other Seated Figures

Placed beside Rembrandt’s early seated self-portraits or his tronies of soldiers and old men, this sheet feels decidedly conversational. It lacks the dramatic shadow theaters of his grander plates, choosing instead a daylight clarity softened by foliage. Yet it shares the hallmark of his figure studies: a refusal to flatter. The sitter’s face is drawn with alert affection; wrinkles are valued for the stories they hold; the beard is lively rather than idealized. The same honesty animates his treatments of beggars and of burghers alike. What changes is the temperature: here, warmth replaces the harsher winds of the street scenes.

The Ethics of Looking

Rembrandt’s treatment of ordinary sitters often reads as an ethic: people deserve to be looked at with patience, however modest their circumstances. In “A Man in an Arboug,” that ethic is embodied in the density of attention given to the hand and the face. Nothing in the print is wasted; every mark contributes to a sense of encounter. The viewer is asked to meet the sitter halfway, to bring curiosity rather than consumption, to imagine the life beyond the frame—the conversation resumed, the tasks set aside for a moment of shade.

The Hand as Narrative Center

The near hand on the table’s edge is small, but it anchors the image. It summarizes the sitter’s state: at rest, not clenched; ready to gesture, not withdrawn. The nails are barely indicated; the knuckles are mapped with a few succinct strokes; a sliver of paper-white lies along the fingers’ ridge where light grazes. In a scene without overt action, the hand supplies narrative: he has paused. The time of the picture is the length of a sentence, the span of a thought held before it vanishes into the air.

Why the Image Persuades

The print persuades because it trusts simple things: shade, posture, and a face that welcomes being seen. There is no theatrical contrivance. Instead we have an outdoor room held together by leaves and fence, a man who has made himself comfortable, and an artist who records the encounter with lines that still feel warm from the plate. The viewer leaves with a feeling of having been in company. That sense of gentle companionship is one of Rembrandt’s quietest achievements.

Conclusion

“A Man in an Arboug” is a hymn to the unremarkable minutes that give human life its softness. It records a pause beneath leaves and treats that pause as worthy of art. The etched lines never shout; they mingle like voices in friendly shade. The figure looks out with curiosity rather than demand, and the arbor holds him the way a city holds its citizens—lightly, with room for air. In this small work from 1642, Rembrandt reminds us that portraiture can be a form of hospitality, and that gardens, like art, are houses we build for attention.