Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

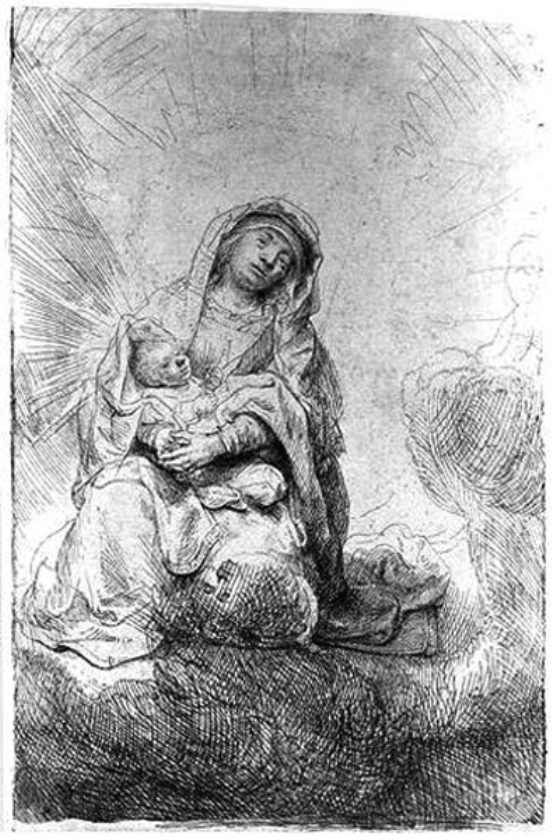

Rembrandt’s “Madonna and Child in the Clouds” (1641) is a concentrated vision of tenderness and theology rendered through the humblest of means: a small etching whose lines breathe like whispered prayer. Seated upon a soft bank of vapor, the Virgin cradles the Christ Child, both figures wrapped in a mantle of light that radiates outward in quick, bright strokes. Below them the world is absent; there is no stable, no architecture, no landscape. Instead Rembrandt suspends the pair within an airy, incandescent space so that form and faith are inseparable. The print’s modest scale invites intimacy, and its daring simplicity transforms a familiar subject into a meditation on light, weight, and the mystery of incarnation.

Composition Suspended Between Earth and Heaven

The entire composition is built around an upward drift. Mary sits solidly, yet she appears to float, her robes pooling upon a cushion of cloud that swells toward the viewer. The oval mass of her body becomes the visual anchor of the sheet, balancing the roving energy of the radiating lines that surround her. The Christ Child lies diagonally across her lap, a crosswise axis that stabilizes the vertical thrust of the light. By removing earthly context, Rembrandt converts the image into a theological proposition made purely through composition: mother and child exist at once in historical flesh and in a timeless sphere of grace.

Light as Theology

In this print, light is not merely illumination; it is meaning. Rembrandt carves rays with a speed and spontaneity that feel immediate, as if the burst were happening in the moment of looking. The brightest reserve of paper collects around Mary’s head and the Child’s limbs, leaving the outer cloud and the lower register in a net of softer hatch. This graduation functions like a visual hymn, announcing sanctity without resorting to a literal halo. Rather than a single, theatrical beam from above, light emanates from within the figures, especially from the Child’s torso and the Virgin’s turned cheek. The impression is of interior radiance, a luminous correlative for the doctrine of divinity housed in human form.

The Virgin’s Expression and the Grammar of Tenderness

Rembrandt’s Madonna is not an idealized statue; she is a woman whose face registers thought and exhaustion alongside love. Her head inclines as if listening to a music only she can hear. The eyelids droop in a state between wakefulness and contemplation, and the mouth softens into a line of acceptance. The pose resists showy sentiment. With characteristic restraint, Rembrandt allows tenderness to surface through the smallest signs: the slight tightening of fingers around the Child, the protective fold of fabric drawn up over the infant’s back, the gentle weight of cheek against shoulder. These cues speak more persuasively than any theatrical gesture, and they allow the viewer to feel close to Mary as a mother as well as a sacred figure.

The Christ Child and the Promise of Motion

The infant is rendered with a few brilliant strokes that capture restlessness and trust in a single contour. One tiny hand flares outward as if testing the air, while the head turns toward the light with an alertness that counters the Virgin’s inward gaze. The diagonal of the Child’s body breaks the stillness and implies future movement. Even in this suspended cloud, history is beginning; potential energy gathers in the limbs that will soon carry the child into the world below. Rembrandt’s economy of description makes the infant feel immediate without sacrificing symbolism.

Drapery as Landscape

Because there is no ground plane or architecture, drapery takes on unusual significance. The folds of Mary’s mantle create their own geography, ridges and valleys that stand in for hills and ravines. The etched line alternates between quick, parallel strokes and deeper, curving hatches that describe thickness, weight, and direction. The lower folds darken into a ledge of cloth that seems to rest upon vapor, giving the figures the necessary visual ballast. This nuanced treatment of fabric allows Rembrandt to keep the composition materially convincing while preserving the spiritual isolation of the scene.

Clouds and the Logic of the Air

Rembrandt’s clouds are neither decorative fluff nor bland backdrops; they are structural. He models the vapor with directional hatching that curves and swells, so the cloud mass seems to lift and support the Virgin like a seat carved from atmosphere. In areas where the cloud dissolves toward light, he thins the line to near invisibility, relying on the white of the paper to do the work. Elsewhere the marks tighten into cross-hatched density, particularly at the lower edge, to create a visual threshold between the viewer and the vision. The result is a believable aerial architecture that honors the paradox at the heart of the subject: the most substantial realities often appear weightless.

The Oval Energy of the Sheet

Although the plate is rectangular, the active composition is distinctly oval. Light radiates in arcs that gather into a rounded nimbus, and the main mass of figures forms an egg-like shape within it. This soft oval concentrates attention and reinforces the sense of enclosure and protection. It also echoes the forms of womb and cradle, subtly aligning sacred iconography with maternal imagery. The eye cannot escape into corners; it orbits the figures in a calm, devotional circuit.

Etching as Drawing, Drawing as Prayer

Rembrandt treats the copper plate as if it were paper. His needle draws with a fluid, exploratory confidence, the lines varying in pressure and speed to record the movement of thought. The radiating rays are not meticulously ruled; they dart and stutter, alive with the tremor of the hand. In the robes he allows errant lines to remain, trusting their energy to convey texture and depth. Even the areas of plate tone—thin films of ink that remain after wiping—become atmospheric aids, darkening the lower cloud so the upper zone glows more brightly. The entire technique communicates presence: we can feel the artist looking, deciding, and believing through his marks.

The Cloud Vision in Rembrandt’s Broader Oeuvre

Rembrandt repeatedly explored visionary space—angels bursting into night, saints visited by light, mothers and infants warmed by a hidden glow. “Madonna and Child in the Clouds” participates in that tradition but stands out for its radical simplicity. There is no narrative setting, no cast of supporting figures, no elaborate iconography. The print refines the theme to its essence: relationship illuminated. In doing so it resonates with other intimate subjects from the early 1640s, including etchings of quiet devotions and small Passion scenes. The focus on the immediate and human, rather than the spectacular, is a hallmark of Rembrandt’s spiritual realism.

Psychological Proximity and Devotional Distance

The print achieves a rare balance between nearness and reverence. We are close enough to sense the warmth of the Child’s skin and the texture of the Virgin’s veil, yet the surrounding light and cloud insulate them from ordinary space. This double position mirrors the viewer’s own experience of sacred images: one approaches to be comforted and taught, yet one also recognizes mystery that cannot be domesticated. Rembrandt provides no barrier—no golden frame within the image, no architectural stage—to keep us back. He relies instead on the dignity of the figures and the centered hush of the composition to command respectful attention.

The Humility of Scale

Great themes often come in small packages in Rembrandt’s hands. The reduced scale of this etching encourages contemplation rather than spectacle. It can be held, studied, and returned to, much like a prayer learned by memory. The absence of busy detail is a kindness to the eye; the viewer can rest in simple relationships of light and form without the pressure to decode a complex program. In this way the print functions almost like a portable altar, a fragment of private devotion amidst daily life.

The Tender Politics of Motherhood

Seventeenth-century images of the Madonna often balanced spiritual ideals with contemporary expectations of motherhood. Rembrandt’s treatment is affectionate and unsentimental. He refuses to dress Mary in elaborate courtly costume or to set her on a throne. Her authority is maternal first, theological second, and the two reinforce each other. By showing the Virgin with lowered eyes and a protective embrace, he suggests leadership through care rather than through distance. This vision would have resonated in a Dutch culture that prized the household as a moral center.

The Radiant Field as Sound

One of the print’s most surprising effects is synesthetic: the rays read like sound. Their rapid outward strokes seem to hum, as if a choir were held just outside the frame. The lines become visual music, measuring time and emotion in expanding rhythms. This effect, subtle yet persistent, is characteristic of Rembrandt’s ability to convert abstract marks into lived sensation. It ensures that the image, though silent, feels alive with praise.

Material Presence and Spiritual Presence

Rembrandt’s gift is to keep the sacred grounded. The Child’s weight is visible in the give of the cloth beneath him; the Virgin’s wrist shows the slightest tension as she supports him; the folds gather dustily in the shadows. These small truths of matter prevent the vision from floating away into sentimentality. The heavenly light does not deny the rub of fabric or the heft of a baby; it reveals them as worthy of notice. The print thus becomes a quiet argument for the holiness of the everyday.

Visual Pathways and the Viewer’s Devotional Journey

The eye’s journey through the image mirrors a modest pilgrimage. We begin at the lower darkness of the cloud, step upward along the cords of drapery, pause at the cradle of arms where the Child rests, and finally lift to the Virgin’s inclined face and the coronal rays. That ascent is gentle and repeatable; each viewing retraces the route, and each time the light seems freshly struck. Rembrandt orchestrates this movement without coercion, trusting the integrity of line and contrast to guide us.

Reception and Lasting Appeal

This etching endures because it offers an experience rather than a lesson. Viewers across beliefs can feel the warmth of human closeness and the soft authority of light. Collectors prize impressions with strong plate tone, where the radiance declares itself most vividly against the shadowed base, but even lighter pulls preserve the essential intimacy. The print encapsulates why Rembrandt’s small works often move as deeply as his monumental canvases: they invite us to meet beauty at the scale of attention.

Conclusion

“Madonna and Child in the Clouds” is a little miracle of line. Without elaborate scenery or grand gestures, Rembrandt creates a space where tenderness becomes luminous and doctrine becomes touchable. The Virgin’s inward glance, the infant’s reaching hand, the folds that seat them upon air, and the rays that hum like prayer combine into a vision at once ordinary and exalted. The print asks only for closeness and quiet, and in return it offers a feeling that outlasts the viewing—a sense that love, rendered faithfully, can suspend time itself.