Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

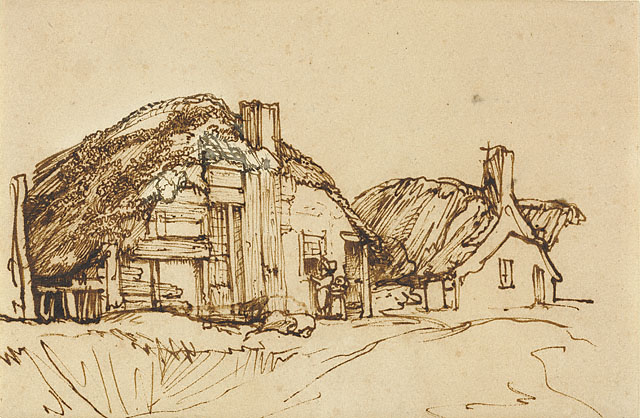

Rembrandt’s “Two Thatched Cottages with Figures at the Window” (1640) is a small but resonant drawing that captures the pulse of everyday Dutch life with a few incisive lines. Executed in pen and brown ink with light wash, the sheet shows two humble houses set along a meandering country lane. The roofs swell like haystacks, patched and tufted; timbers and boards appear irregular yet sturdy; chimneys puncture the silhouettes; and at a central window figures lean out in casual conversation. Nothing grand occurs, yet the scene breathes. In this modest subject, Rembrandt compresses the ethos of the Dutch Golden Age: craftsmanship, economy, attention to weather and light, and a vivid sympathy for ordinary people. The drawing demonstrates why his landscapes and village views remain benchmarks of observational truth—he achieves form, atmosphere, and narrative with the fewest possible strokes.

Subject, Date, and Medium

Dated to 1640, the drawing belongs to the same fertile year as the painter’s celebrated portraits and biblical etchings. Here, however, Rembrandt returns to the countryside he sketched on frequent walks outside Amsterdam. The medium—pen and brown ink, occasionally enriched by a light brown wash—encourages speed and decisiveness. There is no laborious modeling; instead, he relies on the character of the line to imply weight, texture, and light. The choice of subject—two thatched cottages with people visible at a window—signals his commitment to daily life as worthy of art. In a culture often tempted by Italianate fantasies, Rembrandt lets the Dutch village speak its own language.

Composition and the Architecture of Line

The composition is an elegant triangle of attention. The large cottage anchors the left half of the sheet, its façade tipped slightly toward us; the smaller gabled house balances the right. Between them a slender lane arcs forward, inviting the viewer into the space. The eye moves from the dark hatching of the main roof down the vertical timbers to the window where the figures appear, then along the receding thatch of the rear building and over to the crisp profile of the smaller house. Rembrandt controls this journey with line weight. Thick, assertive strokes establish structural edges; lighter, broken lines suggest planes turning away from light. With almost calligraphic confidence, he builds a believable architecture inside an open, breathing field of paper.

Thatched Roofs as Living Forms

The roofs dominate like living organisms. Rembrandt renders thatch with tufts, hooks, and short hatches, letting the pen catch and skip so the texture feels woven rather than drawn. Where the thatch meets wooden walls, he softens the transition with feathery marks that imply moss and weathering. The central ridge swells and sags, honest to the irregularities of rural construction. Even the chimneys—simple rectangular stacks—are textured with quick, dark accents to suggest soot and age. The roofs are not scenery; they are biographies of labor, seasons, and repair.

Timber, Plaster, and the Truth of Surfaces

Beneath the thatch, Rembrandt distinguishes materials with remarkable economy. Vertical boards are indicated by closely spaced, parallel strokes; plastered sections receive broader, unhatched areas, relying on the warm tone of the paper to suggest sunlit chalkiness. Posts and doorframes are not ruler-straight; they tilt and settle, showing how the structures accommodate ground and time. These gentle inaccuracies are not carelessness but observation: country buildings lean, and their strength lies in adaptation. The drawing gains credibility because it has the courage to be specific.

Figures at the Window and the Drama of Everyday Life

At the heart of the scene, small figures lean into the opening of the principal cottage. Their faces are simplified to dots and dashes, yet their posture is readable: one figure emerges from shadow to converse with someone outside; another hovers behind, half-curious. This micro-drama—neighbors exchanging news, a family watching the lane, a vendor pausing—animates the architecture. Rembrandt’s humanism surfaces in the way these tiny presences command attention without mayhem or moralizing. They are the reason the houses feel inhabited, the reason the lane feels like a path rather than a diagram.

Space, Perspective, and the Meandering Lane

Depth in the drawing arises less from mathematical perspective than from layered gesture. The lane curves around a foreground bank—a few confident contour lines—then slides behind the small house at right. Overlapping forms do most of the work: the big cottage obscures the back building, which in turn overlaps the smaller house, which covers a sliver of the lane. The result is a space that reads instantly without technical display. The viewer senses air between elements, a hallmark of Rembrandt’s draughtsmanship: he lets the paper be atmosphere.

Light, Weather, and Negative Space

There is no explicit sun, yet the drawing is built out of light. Rembrandt leaves swaths of paper untouched to represent illuminated plaster and road, then deepens shadow with hatching under eaves and in the recesses of doors and windows. The most striking use of negative space occurs on the right, where the small house stands against near-blank paper: suddenly the thatch and chimneys cut crisp silhouettes, and the whole sheet brightens. This modulation of emptiness and density is Rembrandt’s equivalent of weather. We feel a bright, windy day moving across open country, puddled shadows here, dazzling stops of light there.

Gesture and the Intelligence of the Pen

Rembrandt’s pen lines are not monotonous; they accelerate, stall, hook, and cross. A single stroke can start as a thin feeler, fatten mid-course with pressure, and feather out at the end. Such gestures convey the character of materials and the artist’s own curiosity. For instance, the broken hatchings atop the big roof suggest both uneven straw tips and the gust of the pen—a double truth. The more we look, the more we notice edits: a window first planned smaller, then expanded; a ridge reinforced; a shadow deepened. These are not mistakes to be hidden; they are the living record of seeing.

Comparison with Rembrandt’s Landscape Drawings and Etchings

“Two Thatched Cottages with Figures at the Window” has cousins among Rembrandt’s countryside sketches and etched landscapes. Like the famous “Cottage with Dutch Barn,” this drawing favors low buildings and humble paths; like his etched “Small Gray Landscape,” it uses linear economy to imply wide air. But the present sheet is unusually intimate. Instead of a river or panoramic view, we are pressed close to façade and window, as if pausing mid-walk. In his etchings Rembrandt often adds sky and distant horizons; here he lets the roofs be the horizon, emphasizing the micro-topography of a village street.

Dutch Culture and the Poetics of the Ordinary

The drawing resonates with the Republic’s esteem for work, thrift, and domestic stability. The thatch implies agricultural rhythms; the timber repairs speak of maintenance; the figures at the window make the house a social instrument. This fidelity to the ordinary sets Rembrandt apart from artists who peopled their landscapes with shepherds borrowed from Italy. His Netherlands is not decorated with allegory but lived in with attention. The sheet becomes a poem of the ordinary: a praise of cottages that shelter, windows that frame conversation, lanes that meet the feet of passersby.

Scale and Intimacy

Small drawings invite private viewing. This sheet likely moved through hands, close to eyes, where the viewer could trace lines almost at the speed they were laid down. That intimacy breeds empathy. We do not stand in a gallery looking at a staged scene; we share a page where the artist thought aloud. The scale also supports the theme: cottages and quiet conversation suit a format that asks us to lean in and listen.

The Rhythm of Repair and Time

Rembrandt’s cottages are not new. One sees patched thatch, mismatched boards, slightly cocked chimneys. Yet the buildings are not decrepit; they are resilient. This rhythm of repair—annual re-thatching, seasonal shoring, daily sweeping—is the unseen narrative of the sheet. The figures at the window inhabit houses with history. Such attention to the dignity of maintenance anticipates a modern sensibility: beauty not as perfection but as care over time.

Materials and the Look of Speed

Pen and brown ink allow a kind of shorthand impossible in oil. Rembrandt can signal an entire roof with a dozen quick strokes, then return to worry a window edge into precision. The brown wash, if present, is floated sparingly to weight shadows or warm an entire plane. The paper’s slight tooth catches the ink unpredictably, producing minute raggedness along edges that reads as texture. The drawing’s energy derives from this intimacy between medium and subject: a rustic scene written with rustic marks.

Narrative Possibilities Beyond the Frame

Although the drawing records a single moment, it teems with narrative potential. Where does the lane lead beyond the right-hand cottage? Has a traveler just approached, prompting the window figures’ interest? Does smoke slip from an unseen kitchen? Rembrandt gives hints but refuses to close the story. That openness mirrors the experience of walking through a village: you catch a fragment of conversation, a child’s laugh, the thud of a bucket, then you move on, carrying a small world inside you.

Why the Drawing Still Feels Fresh

The sheet feels modern because it privileges observation over formula. The cottages are irregular and specific; the lines are exploratory; the space breathes. Photographers and urban sketchers today recognize Rembrandt’s method: decisive marks that allow for correction, a composition anchored by strong silhouettes, a respect for the everyday scene. The drawing also honors slowness. It asks us to stop, attend to surfaces and edges, and acknowledge the lives behind a window.

Lessons in Seeing from a Master

From this single sheet we can extract a short handbook on seeing. Start with structure: place the big forms with bold lines. Vary pressure to keep edges alive. Use negative space as light. Let texture emerge from gesture rather than from laborious cross-hatching. Insert a human presence, however small, to clarify scale and purpose. Above all, stop before the paper is crowded. Rembrandt leaves generous breathing room around the cottages; the lane is mostly empty line; distant forms are suggested, not insisted upon. The scene is complete precisely because nothing extraneous remains.

Conclusion

“Two Thatched Cottages with Figures at the Window” distills Rembrandt’s landscape intelligence into an intimate statement. With pen and a touch of wash he builds architecture, atmosphere, and story. The swelling thatch and leaning timbers express time and care; the figures at the window supply human warmth; the curving lane and open paper offer air. No special effects are needed. The drawing succeeds because it believes that attention dignifies the world. Nearly four centuries later, its lines still carry the breeze of a Dutch afternoon and the murmur of neighbors leaning into a window to share a moment that would otherwise have vanished.