Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

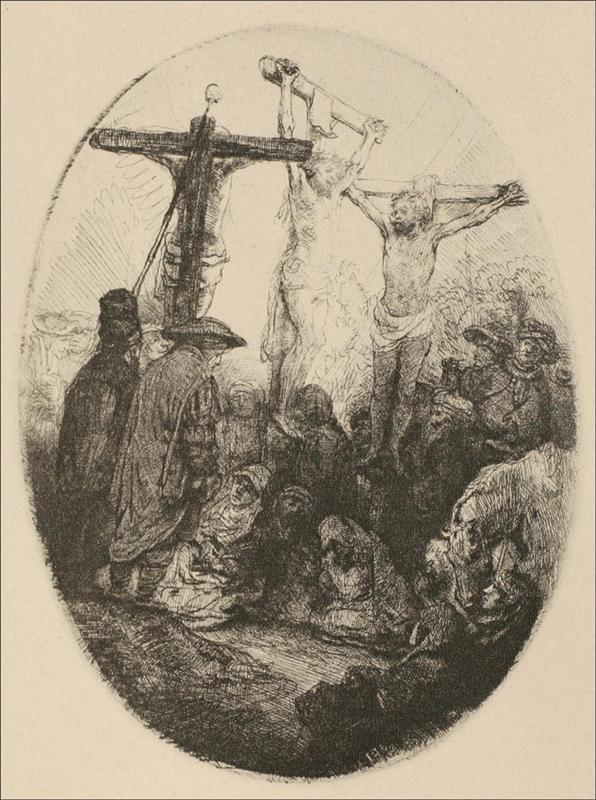

Rembrandt’s “The Crucifixion, an Oval Plate” (1640) is a small etching with immense spiritual voltage. Composed within an oval field, the scene compresses Calvary into a chamber of light and shadow where emotion ripples through a dense crowd at the foot of three crosses. Christ occupies the central stake, his body a column of pale light; the two thieves flank him, one in shadow at the left, the other illuminated at the right. Below, clumps of mourners and soldiers form a dark wreath that encircles the central miracle. With an economy of etched line and the orchestration of chiaroscuro that only Rembrandt could command, the plate transforms copper into a living theatre of grief, doubt, and revelation.

The Oval as Spiritual Stage

The oval format is not a curiosity but a dramaturgical choice. Its curved boundary behaves like a lens, pulling the eye inward and preventing visual escape. Unlike a rectangle, which allows peripheral digressions, the oval gathers attention into a devotional focus, echoing the shape of a medallion or reliquary. Rembrandt allows the upper half of the oval to bloom with light around the crucified figures, while the lower half thickens into an earthy crescent of shadow where humanity kneels, whispers, and recoils. This geometry turns the print into a visual prayer: heaven arcing above, earth weighted below, the cross standing as hinge between realms.

Light, Shadow, and the Language of Grace

The etching speaks through light. Christ’s body is etched with fewer, softer lines than the surrounding crowd, permitting the white of the paper to shine through and wrap him in an otherworldly radiance. The thief at the right receives an echo of that light, hinting at the Gospel promise—“Today you will be with me in paradise.” The thief at the left remains in comparative darkness, an interpretive nod to hardness of heart. Around the hill, Rembrandt summons darkness with dense cross-hatching and plate tone, fusing soldiers, spectators, and women into a shadowy mass. The distribution of luminosity is theological without preaching; grace becomes legible as light.

Composition and the Arc of Attention

Within the oval Rembrandt designs a choreography for the eye. We first meet the central figure of Christ, whose outstretched arms anchor the composition’s horizontal axis. From there, our gaze slips laterally to the two thieves, then descends in a semicircular sweep through the crowd: from the soldiers’ helmets on the left, past the kneeling women, to the hunched forms in the foreground, and back to the cluster of onlookers at the right. Finally the movement rises again along the upright beam of the cross. This peripatetic path mirrors the narrative experience of the Passion—looking, losing hope, and returning to the one who suffers at the center.

Crowd Psychology and the Theatre of Witness

The lower half of the print is a study in crowd behavior. Rembrandt segments the throng into pockets of response: a pair of soldiers who chat, indifferent; men craning for spectacle; women crouched in anguish; a hooded figure who seems to turn away in private prayer. He resists detailed portraiture, opting instead for archetypes of reaction. This choice universalizes the scene. The oval becomes a mirror where viewers recognize themselves—curious, grieving, skeptical, or fearful—in the densely hatched faces below the cross. The Crucifixion is not a distant legend but a drama that repeatedly implicates onlookers.

The Mourners and the Body Language of Sorrow

At the foot of the central cross, a knot of women folds into the ground, their bodies almost swallowed by shadow. The gestures are telling: bent heads, clasped hands, shoulders hunched against a cold wind of grief. Rembrandt sculpts sorrow with line density, letting contours dissolve into darkness as if grief itself were consuming form. Amid these figures is likely the Virgin Mary, supported by companions; the anonymity of faces protects the inwardness of their lament. In this small cluster, the print finds its deepest human truth: love holding vigil under an unbearable brightness.

Soldiers, Officials, and the Machinery of Order

The left flank is anchored by figures in helmets and heavy cloaks. Their upright postures and squared shoulders inject a chill of administration into the scene—the presence of a state apparatus that ensures the execution proceeds without disturbance. Rembrandt etches them with firmer, straighter lines than the mourners, conveying hardness and duty. They are not caricatured as monsters; rather, they embody the cold efficiency with which authority can frame and normalize violence. Their proximity to the darkest of the thieves forms a moral parallel: unrepentance at one cross, unfeeling order at the other.

Christ as Column of Mercy

Christ’s figure is elegant and unsentimental. Rembrandt avoids florid anatomy, stressing instead the logic of weight and stretch—arms taut, ribcage lifted, abdomen slackening toward the loincloth. The head tilts, not theatrically but naturally, and the feet cross in a modest knot of lines. What arrests the viewer is not pose but atmosphere: the paper around him glows, an effect produced by sparing the plate of heavy bites in this zone and wiping the ink lightly to retain a mist of plate tone elsewhere. The result is a luminous silence around Christ, a space into which grief and mockery fall quiet.

The Two Thieves and the Theology of Asymmetry

Rembrandt’s placement of the thieves is not neutral. The figure at Christ’s right—the penitent—is bathed in a sympathetic light, his form more legible; the figure at left sinks into a darker surround, his torso turning away. This asymmetry visualizes the spiritual divergence narrated in the Gospels without resorting to labels. The viewer senses that choices are being made even at the lip of death and that the light which crowns the central cross spills toward those who open to it.

Etched Line as Weather and Ground

The sky above Calvary is not described by clouds but by subtle sweeps of line and reserved paper whites that imply a breaking radiance. Rembrandt refuses literal sunbursts; instead he registers atmosphere as if the world itself were holding its breath. The ground at the bottom of the oval is heavily worked, the hatchings laid at angles that catch the light like clods of earth. This roughness allies the foreground with the mourners’ grief; it is soil that has known tears.

The Oval Edge and the Ethics of Framing

The curved boundary truncates peripheral details and softens the transition from image to paper. The effect is votive: the scene appears as if mounted within a devotional medallion. That framing principle carries ethical weight. It asks viewers to hold the event, not skim past it, and to treat the spectacle not as entertainment but as an object for contemplation. In a century enamored with prints as collectable commodities, Rembrandt uses the oval to sanctify attention.

Silence, Sound, and the Imagination of the Plate

Although the print is mute, it invites an acoustic reading. The dense black at bottom hums with low murmurs, the rustle of cloaks, the dull clink of armor. The pale circle around Christ is a high, clear note of silence. By modulating line density like volume, Rembrandt writes sound into the copper. The viewer’s body supplies the rest: breath slows at the center, then resumes as the eye descends into the crowd’s voiced sorrow.

Gesture, Hands, and the Rhetoric of Conversion

Look closely at the figures to the right of the central cross: several hands point, press against faces, or clasp in prayer. One arm swings upward in a dramatic diagonal, an index of shock or proclamation. Hands in Rembrandt always argue; they are verbs. Here they stage the grammar of response—accusation, intercession, despair, and surrender. Without a single inscribed text, the plate speaks in a language of gesture that crosses centuries and denominations.

Printing Choices and the Breath of Plate Tone

Rembrandt was meticulous in printing his plates for atmospheric effect. Many impressions of this oval show a delicate veil of plate tone, especially around the lower half, which fuses the crowd into a single mass while preserving crispness in the central crucified figure. The plate was likely wiped more cleanly in the bright halo at top, while a richer ink film remained in the shadowed crowd. Printing thus operates like lighting design, ensuring that the devotional emphasis remains unwavering.

Comparison with Rembrandt’s Larger Passion Works

Placed beside Rembrandt’s monumental treatments of the Passion—such as “The Three Crosses” of the 1650s—this 1640 oval appears reserved, even intimate. The later drypoint unleashes cataracts of darkness and scoured light; the oval chooses persuasion over thunder. Yet the seeds of the mature vision are present: light as grace, crowd as mirror, Christ as still point. The oval’s modesty lets us examine these ideas at chamber scale, where every stroke matters and intimacy heightens empathy.

The Human Economy of the Scene

The print maps the economy of cost and consolation. At the top, cost is paid in the body on the central cross; at the bottom, consolation flickers in the huddled community who refuses to leave. Between them flows a circulation of sight: Christ’s downward gaze meets the gathered sorrow; their upturned faces send love back into the light. No single figure monopolizes meaning; instead, the community’s grief and the crucified’s patience interpret each other.

Theological Nuance Without Iconographic Noise

Rembrandt proves that complex theology can be stated with visual simplicity. He avoids inscriptions, angels, apocalyptic clouds, or allegorical personifications. The doctrine of atonement, the promise to the penitent thief, the scandal of empire’s cruelty, and the consolations of fellowship are all here—but carried in light, posture, and proximity rather than in symbols. The result is a scene that speaks across confessional lines. Devout viewers read it as worship; secular viewers read it as an unsurpassed study in human endurance.

Viewer Position and Devotional Intimacy

The foreground patch of illuminated earth at the bottom edge functions as a threshold. It invites us to kneel with the mourners and to occupy the same light that grazes their heads. This is not a distant panorama viewed from a hill; it is an invitation to presence. The oval presses the viewer close, creating a felt participation that dignifies grief and makes indifference difficult. One leaves the image changed by proximity.

The Lasting Modernity of a Small Print

Even in an age saturated with images, the oval remains startling. Its quiet power comes from concentration: every line earns its place. Contemporary viewers recognize the print’s psychological realism—the plurality of reactions inside a single crowd, the terrible normalcy of soldiers on duty, the way light can consecrate an ordinary afternoon. The piece anticipates the documentary eye of later centuries while preserving the ancient depth of devotional art. Its smallness enhances its authority; attention becomes part of the meaning.

Conclusion

“The Crucifixion, an Oval Plate” is a masterclass in how etching can carry the fullness of painting and the intimacy of drawing. Rembrandt builds a theology of light within a simple curve of paper, staging humanity’s responses to suffering with compassionate precision. The central Christ glows not as spectacle but as still point; the thieves articulate choice at the edge of death; the crowd becomes a mirror; and the mourners at the foot of the cross teach us how love behaves under pressure. In the oval we find not a summary of doctrine but an encounter—quiet, concentrated, and inexhaustible—where line turns into breath and shadow confesses the reality of grace.