Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

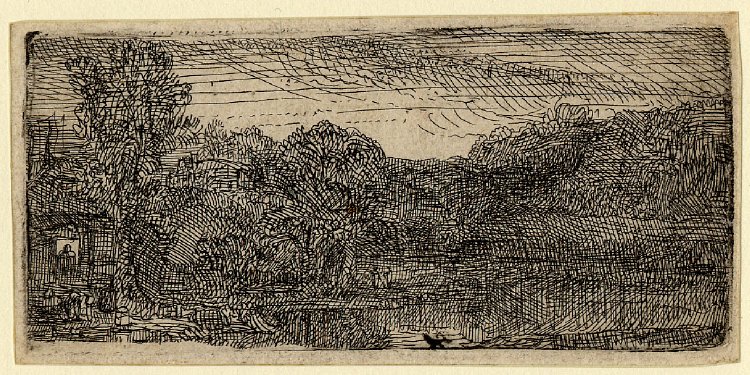

Rembrandt’s “Small gray landscape, a house and trees beside a pool” (1640) is a miniature drama of line and light. Created as a tiny etching, it captures a riverbank and a thicket of trees massed around a quiet pool, with a modest house tucked on the left and a low sky streaked with shallow hatchings. The scene is intimate and unassuming, yet its compressed scale contains a complete world: settlement and shelter, water and reflection, foliage and air, a path for the eye that loops gently through foreground, middle ground, and distance. With the most economical means—short lines, cross-hatching, and reserves of untouched paper—Rembrandt shapes atmosphere and depth, demonstrating how the language of printmaking can rival painting in expressive power.

A Landscape Measured in Lines

At first glance the print seems a weave of marks. Step closer and the logic appears. Vertical strokes stack to build tree trunks; curved hatching rounds clumps of foliage; tight parallel lines lay down the glassy surface of the pool; and an open mesh of airy diagonals stretches across the sky. The image is a grammar lesson in how different directions of line describe different substances. The pleasure lies in the coherence of this syntax: no area is left inert. Even shadowed thickets breathe because their cross-hatching never resolves into a dead block; the white of the paper glints between strokes like scattered sunlight.

Scale, Intimacy, and the Act of Looking

The plate’s small size demands the viewer’s closeness. This intimacy is not incidental; it is the core experience the print offers. Where a large canvas can overwhelm with spectacle, a miniature etching invites a form of looking akin to reading—a slow navigation through clauses of mark-making. Rembrandt understood that proximity changes attention. The diminutive format turns the viewer into a walker along the bank, peering over reeds and tracing the silhouette of leaves against the sky. The landscape becomes not a vista but a companion.

Composition and the Geometry of Calm

The composition is a gentle arc from left to right. On the far left the house anchors the scene—its tiny doorway and roofline forming a clear geometry among the organic forms. A tall tree rises beside it like a guardian column. From there the foliage swells toward the center into a layered mass, then recedes into a low range of dark forms that cushion the far bank. The pool occupies the lower third as a band of quiet tone, its surface broken by the faintest ripples. Above, the sky is an airy field, its diagonal hatchings sweeping toward the upper right and curving back like a sheltering canopy. This organization produces steadiness: vertical, horizontal, and diagonal forces counterbalance each other, keeping the little image poised.

The House as Human Measure

Though barely larger than a thumbnail, the house is crucial. It supplies scale, narrative suggestion, and moral center. A human figure seems to stand or sit within its dark doorway, a tiny emblem of habitation amid nature. This presence tilts the landscape toward the domestic rather than the sublime. It suggests that the water has uses—washing, watering, reflection—and that the trees provide shelter and fuel. The house also acts as a visual hinge. Its rectilinear silhouette asserts clarity against the lively foliage, giving the eye a place to rest before drifting into the thicket.

Water as Mirror and Pause

The pool is a compositional pause. Rembrandt keeps its tone lighter than the tree masses, setting it apart as a breathing space. The etched lines tracking its surface curve gently to catch reflections without literal mirroring; a few darker passages near the bank suggest depth and shadow. Because the pool occupies the foreground plane, it functions like an invitation or threshold. We stand at its edge, aware of a step down, a coolness, a surface that both appears and conceals. In a print that privileges brevity, this calm band becomes eloquent.

Trees and the Architecture of Foliage

Rembrandt’s trees are not decorative clumps; they are built. He stacks short strokes to simulate the weight of leaves and the density of branches, then cuts deeper shadows into the masses with layered cross-hatching. Trunks emerge from these tapestries as firmer verticals, sometimes indicated with a broken line that lets light flicker along bark. Yet he never fetishizes detail. No leaf is drawn; instead, the rhythm of marks conjures leafiness. The result is a living architecture: foliage that occupies space, catches wind, and leans toward water.

Sky, Weather, and the Breath of the Plate

The sky is the most abstract area—no clouds in outline, no birds, just a sweep of diagonal lines thinning toward the horizon. That thinning is crucial. As the hatchings relax, the paper’s untouched brightness glows through, creating the sensation of depth and distance. Diagonal directionality suggests a moving air mass, as if a breeze were combing the high atmosphere. This subtle weather ties the whole landscape together. The same diagonal rhythms nudge the treetops and whisper over the pool, so that line becomes climate.

The Logic of Depth in a Narrow Space

Creating depth on a small plate is a magician’s task. Rembrandt accomplishes it with value, line density, and overlapping planes. Foreground lines are more widely spaced and visible; midground masses are darker and more densely hatched; the distant ridge is flattened into a continuous shape that pushes back without losing substance. The pool’s near bank, drawn with long horizontal strokes, recedes under a few darker accents, while the far bank rises with vertical textures. Nothing is diagrammatic, yet every element contributes to the illusion of layered space.

Etching Technique as Narrative

Technical choices become storytelling. The darker bite of acid in the central thicket makes the grove feel thick and cool; lighter bitten lines in the sky keep the air buoyant; the house is drawn with firm, decisive strokes that convey human intention. Even the tiny burr—the velvety ridge that forms when a line is bitten energetically—traps ink and turns shadows lush. Plate tone, the thin veil of ink left intentionally on the surface, likely infuses the pool and sky with a soft gray that binds the marks into atmosphere. These are not accidents; they are narrative tools that turn copper and ink into place and time.

The Dutch Eye for Habitable Nature

Seventeenth-century Dutch art rarely sought Alpine awe. It preferred landscapes where people could live—water managed by dikes and canals, fields bounded by hedges, windmills standing like citizens. This etching belongs to that tradition. The wilderness is tamed to human scale; the house participates in the scene’s rhythm; the pool is approachable. Rembrandt’s difference lies in his refusal of postcard neatness. He leaves edges ragged, trees slightly unruly, sky open. The result is convincing habitation rather than decorative order.

The Viewer’s Route Through the Image

The print invites a patient walk. We enter at the house, step along the bank, and wander into the central grove where darks compress. Our gaze then drifts across the pool’s quiet band to the far bank and climbs the low ridge toward the right, where the sky’s diagonals carry us up and back across the top, returning us to the opening left edge. This circular path feels like a stroll taken at dusk or dawn when the world is hushed. The rhythm of looking matches the rhythm of etched strokes, aligning eye and hand across centuries.

A Pocket Notebook of the World

The “small gray landscape” reads like a page from a notebook: concise yet abundant. It may well have been etched from memory or from a quick study made outdoors. Rembrandt compresses observation into an architecture of marks that can be carried in the pocket, printed, and shared. In this portability lies one of printmaking’s social powers. Tiny landscapes like this could be owned by students, artisans, and merchants—people who might never afford a large oil painting—while still giving them access to the poetry of place.

Time of Day and the Ethics of Quiet

The shallow contrasts and the long, even hatchings overhead imply calm light—perhaps the hour before sunset or the first coolness of morning. That time of day suits the scene’s ethical tone. Nothing in the print performs; the house is modest, the trees unheroic, the pool free of spectacle. Rembrandt offers a modest proposition: that quiet seeing is a form of knowledge and that domestic nature can sustain the soul as surely as cathedrals or palaces do. In a compact rectangle, he practices gratitude.

Dialogue with Rembrandt’s Larger Landscapes

Placed beside Rembrandt’s painted panoramas—such as “Landscape with a Long Arched Bridge”—this etching feels like a whispered aside. The paintings deploy broad tonal masses and dramatic weather; the etching attends to the local music of trunks, reeds, and rooflines. Yet both share key convictions: water as structural axis, trees as living architecture, and light as the true protagonist. The small print concentrates those convictions into a haiku of line.

Why the Image Still Speaks

Modern viewers, attuned to photography’s snapshots and to the restorative appeal of small green spaces, find this print uncannily current. It looks like a park edge glimpsed on a walk, a pocket of trees near a city. The graphic economy reads almost like a pen sketch, a language of immediacy familiar from contemporary drawing. Above all, the print rewards attention—an increasingly scarce resource—by giving back more than its size promises. Lean in, and a whole landscape reveals itself from a handful of marks.

Conclusion

“Small gray landscape, a house and trees beside a pool” proves that grandeur is not a function of size. On a plate scarcely larger than a hand, Rembrandt builds settlement, foliage, water, air, and time. He calibrates line directions to mimic material, uses value to stage depth, and reserves paper whites to breathe light into the scene. The modest house calibrates scale and meaning; the pool offers a pause for the eye; the sky’s diagonal hatchings drift like weather across the whole. What remains after long looking is a sense of well-being—the feeling that the world, attended to with care, arranges itself into comprehensible harmony. In this miniature, Rembrandt gives us not just a view but a practice: to look slowly, to let small things suffice, and to find home along the quiet edge of water and trees.