Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

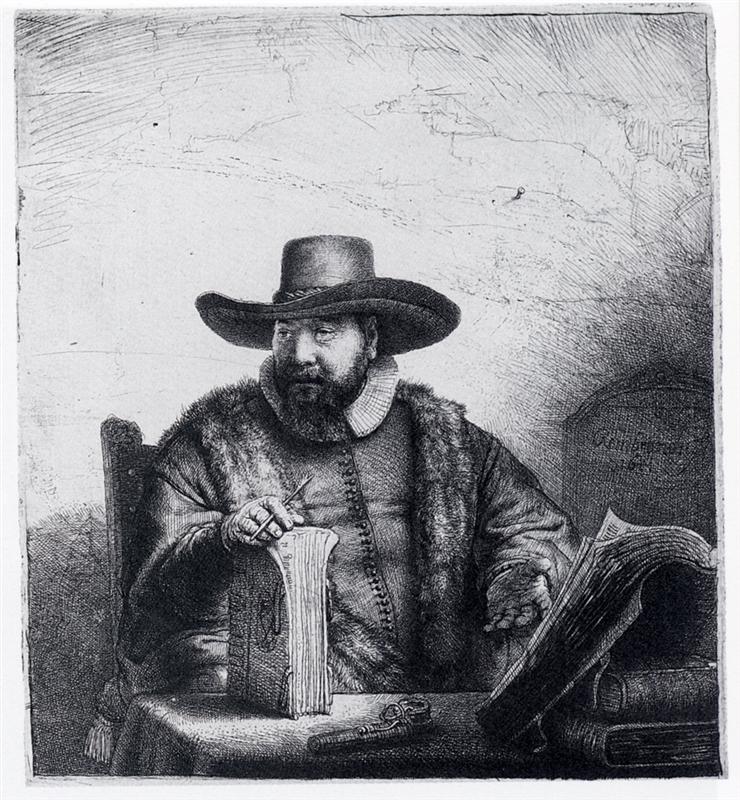

Rembrandt’s “Portrait of Cornelis Claesz” (1640) is an etching that turns a seated burgher into a world. A broad-brimmed hat anchors the composition; a fur-lined coat swells across the torso; great folios lie open and closed on the table like architectural elements; a pen, a knife for trimming quills, and a ledger share space with a pistol; behind the sitter, the wall curves away into a dome of fine hatchings. At the center of this material stage sits Cornelis Claesz, steady-eyed and deliberate, right hand poised with the tool of his trade and left hand opening in a small, conversational gesture. More than a likeness, the print is a portrait of work—of the habits, tools, risks, and satisfactions that defined a successful Amsterdam life in the middle of the seventeenth century.

Who Was Cornelis Claesz?

The exact identity of Rembrandt’s sitter—one of several Cornelis Claeszen who traded and held office in Amsterdam—matters less than the type he embodies. He is a prosperous man of letters and ledgers, someone at ease amid books and accounts, yet not far removed from the gun that rests on the table, a reminder that commerce and civic duty required readiness. Rembrandt does not flatter him into an emblem of abstract virtue; he makes him particular. The face is broad and alert, the beard carefully maintained, the gaze slightly off to the side as if thinking through a calculation before he speaks. This is a man who spends his days adding, signing, checking, and deciding, and the print honors that mental stamina.

Composition as a Theater of Work

Rembrandt composes the plate as a compact stage. The table’s front edge forms the proscenium; the sitter leans slightly forward, placing us in the privileged position of someone called to consult. The great vertical of the standing book at left balances the sloped diagonal of the open folio at right. Between these two pillars rises the triangle of hat, cheeks, and collar. The surrounding architecture is implied rather than described: a lightly etched vault of space that keeps the eye from getting lost outside the action. Everything funnels attention toward the sitter’s hands—one gripping a quill knife, the other open, as if weighing the argument or inviting a signature. The entire composition therefore reads as transactional and conversational. We are not intruders; we are participants.

The Face and the Gaze

The most magnetic element is Claesz’s face. Rembrandt builds it with an orchestration of small parallel strokes that thicken at the cheeks and soften over the lips, giving the sensation of living skin. The eyes are set under the shade of the hat but glint with two careful highlights. The mouth is neither grim nor smiling; it tilts with a trace of humor, the sort of expression that keeps negotiations cordial while remaining firm. Wrinkles deepen around the eyes and nose where thought lives. This is the psychology of labor: a person not posing for the ages but pausing between acts of judgment.

Costume and the Texture of Power

Clothing in this portrait is not mere fashion; it is an index of status and climate. The fur lining breathes warmth and weight; the collar is crisp but not showy; the wide hat’s brim doubles as a tool of vision, shading the eyes so the work on the table can be seen without glare. Rembrandt renders each material with its own hatching grammar. Short, burr-rich strokes make the fur plush; long, parallel lines soften into the felt of the hat; tiny, controlled crosshatching articulates the linen of the collar. The craft of the etcher mirrors the craft of the sitter. Both deal in fineness and decisions.

Books, Ledgers, and the Republic of Paper

Few portraits feature books as characters with such presence. The upright volume at left stands like a sentry, its spine creased from use, its pages ruffled. The open folio at right arches like a bridge, the curved page weighted by a heavy corner to keep it from closing. These objects are not generic props; they are the tools of a life. In the Dutch Republic, paper empires—contracts, bills of exchange, shipping manifests, notarial acts—moved goods and money. Rembrandt understands this world and gives it gravity. The books supply not only context but visual rhythm. Their vertical and diagonal planes build an architecture around the sitter’s head, a library made from line.

The Tabletop Still Life

Across the front edge an understated still life stretches: the pistol, a quill or two, perhaps a seal, the swell of the book’s pages, the cloth that covers the table. The pistol is not a threat; it is a reality. Dutch citizens of rank often bore arms in civic militias, and merchants who traveled or kept cash nearby valued protection. The gun’s presence reminds us that prosperity required vigilance. Rembrandt etches it with restraint, giving the barrel a quiet sheen and the stock a tactile curve that catches the light. It balances the delicacy of the quill. Word and weapon share a plane, a miniature of the Republic’s dual reliance on law and force.

Chiaroscuro in Etched Line

Although a black-and-white medium, etching has its own chiaroscuro, and Rembrandt wields it masterfully. He builds a cavern of shadow under the brim of the hat and around the shoulders, then opens a cone of lighter value across the face and hands. The background is treated with long, mostly horizontal hatchings that thin as they approach the light source. The vaulting effect subtly enlarges the sitter’s presence. Contrast is strongest where Rembrandt wants us to look—the meeting of sleeve and table, the dense grain of the fur, the crisp shadow along the open book’s paper edge. Light appears to fall from above and slightly left, creating a credible, workmanlike daylight rather than theatrical illumination.

The Authority of the Line

Rembrandt’s etched line has character, and character is the subject here. In some places the line is clean and assertive; in others it frays into burr, leaving a velvety fringe that reads as wear or softness. The artist varies pressure and speed so that lines describe not only contour but substance. On the face, stipple and short hatchings fuse into an analog of pores and beard. On the books, long strokes become the grain and warp of paper. The viewer senses the artist’s hand deciding second by second—choosing between clarity and suggestion. This decision-making parallels Claesz’s own work with pages and sums, and the portrait becomes a meeting of two craftspeople: one of ink on copper, one of ink on paper.

Space, Distance, and the Sense of Room

The wall behind the sitter is no mere backdrop. Rembrandt activates it with faint scrapes and stipples that suggest a plaster surface lit obliquely. A tombstone shape—possibly a ledger board or memorial tablet—emerges on the right, reinforcing the image of a man situated in a community with memory and law. The dome-like sweep of hatching at top left generates an architectural feel without literal arches, giving the impression of a vaulted chamber or an alcove within a countinghouse. This sense of room bolsters the sitter’s authority while preventing the portrait from floating in an abstract void.

Gesture and the Rhetoric of Hands

Hands are the portrait’s most eloquent speakers. The right hand, grasping the quill knife, is ready to trim and write; the gesture is forward, implicating the viewer in the next act—sign here, initial there, approve this clause. The left hand opens palm up, a civil invitation to conversation, or perhaps a warning that the figures will not add up unless something changes. Rembrandt renders knuckle, nail, and palm with anatomical conviction, showing a hand used to both delicacy and pressure. In the language of the painting, the hands are verbs while the face is the subject.

Psychology without Flattery

Rembrandt refuses to smooth away heaviness under the chin or the fleshy pressure against the collar. He honors weight as a form of presence. Yet he also guards against caricature. The sitter’s dignity arises from proportion and from the calm with which he inhabits his space. Even the fur, a potential vehicle for ostentation, is presented as practical insulation, not as display. This honest regard for the body confers ethical substance on the portrait. The man is neither romanticized nor mocked; he is regarded.

The Hat as Crown and Shade

The broad hat does double duty. It crowns Claesz with social standing—the respectable silhouette of a gentleman in the Republic—and it shades his eyes, enabling sustained focus on the labor before him. Rembrandt enjoys the hat’s geometry. Its brim sweeps in a strong ellipse that echoes the open book’s curve, linking head and work. The hat’s band, described by a few crisp lines, adds a note of order: even the adornment is controlled. In a culture that prized understatement, this restraint reads as virtue.

Comparison with Painted Burgher Portraits

Compared to Rembrandt’s painted portraits of merchants and regents, the etching feels both more intimate and more analytical. Oil paint wraps a sitter in atmosphere; etched line reveals structure and habit. Here, the lack of color focuses attention on the grammar of work. The open book’s white is paper-white; the hands’ light is the copper’s light. This clarity supports the portrait’s thesis: the human person emerges from relations to tools, pages, tables, and rooms. In that sense, the print is closer to a still life that has learned to speak.

The Viewer’s Path

Our eye enters at the open book’s luminous curve, moves to the hand that holds the knife, climbs to the face, and glides under the hat’s brim to the far hand. From there it returns to the pistol and the closed volumes before restarting the circuit. This loop mimics the sitter’s own daily routines: open, note, consider, sign, secure, and close. The portrait thereby educates our looking, teaching us to linger where decisions concentrate.

Etching as a Democratic Medium

Rembrandt’s choice of etching for such a portrait is significant. Prints multiply; they circulate; they pass through hands like the very documents Claesz manages. By making the image reproducible, Rembrandt aligns the sitter with the public sphere. He becomes not a private noble, but a citizen whose likeness can enter market stalls, homes, and portfolios. The medium extends the sitter’s social presence just as his books extend his business reach.

Time, Wear, and the Aura of Use

Many impressions of this plate show fine wear on certain hatchings, a softening that matches the subject’s world of handled things. The open book’s frayed page edges, the smoothed table cloth, the polished pistol stock—all suggest years of use. Rembrandt’s attention to such patina prevents the portrait from feeling staged. This is not a studio fantasy; it is a recognition of how objects and people age together in the practice of duty.

Legacy and Modern Resonance

The portrait resonates today because it represents a dignity often overlooked: the dignity of administrative labor. In a time that celebrates innovators and warriors, Rembrandt devotes his art to the person who keeps accounts accurate and agreements honored. The mixture of pen and pistol also feels contemporary, acknowledging that law and security must accompany enterprise. The sitter’s patient gaze across a table strewn with papers could be any thoughtful professional’s in any century.

Conclusion

“Portrait of Cornelis Claesz” is a compact masterpiece of character and context. Rembrandt stages a modest drama of civic life: a man at a desk, books open, tools at hand, ready to speak and to write. The composition’s balance, the etched line’s authority, and the interplay of materials create a portrait that is at once intimate and public, tactile and thoughtful. We come away believing in the sitter’s competence and integrity because the print itself is competent and integral—every mark purposeful, every object in service of presence. In the quiet company of paper and fur, quill and pistol, Rembrandt shows how a life can be defined by the work it does well.