Image source: wikiart.org

A Head That Fills the Room

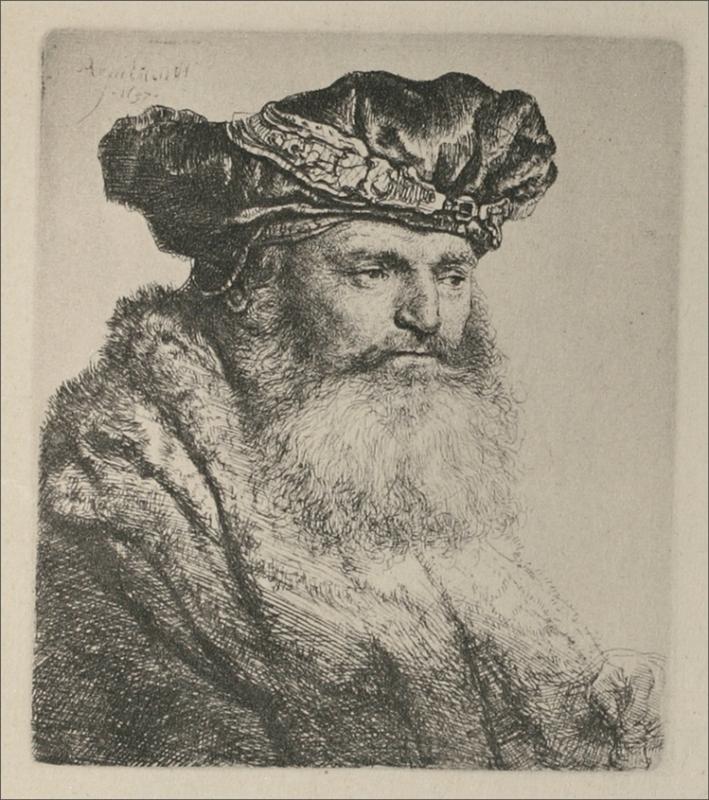

Rembrandt’s “An Old Man, Wearing a Rich Velvet Cap” from 1637 is a small etching that expands in the mind like a life-size painting. The plate grants us a three-quarter view of a bearded elder whose head and shoulders occupy nearly the whole field. A luxurious cap crowns the skull; a furred mantle spills in dark waves across the chest; the mouth sets into a line that is neither resigned nor severe; the eyes look slightly down and aside, as though weighing something that will not fit into words. The likeness is at once intimate and monumental. In this compressed space, Rembrandt builds a world of textures—skin, hair, velvet, fur, and air—using nothing more than networks of bitten lines and the white breath of paper.

Etching As Sculpture in Light

The technique is etching, likely enlivened with touches of drypoint in the softer passages. Where engraving tends toward the metallic and predetermined, etching invites a drawn, improvisational touch. Rembrandt draws into wax, the lines are bitten by acid, ink fills the channels, and the press transfers that ink to damp paper. Every step invites decisions about pressure, wiping, and plate tone. In this plate he sculpts the beard with overlapping, tapering strokes that turn like a river delta; he thickens the velvet cap with dense crosshatching that glows because the surrounding paper is allowed to breathe; and he varieties the fur with splayed, errant marks that mimic guard hairs. The result is not a mere inventory of materials but an orchestration of how light behaves on those materials.

A Composition That Crowns Dignity

The sitter’s head sits high within the frame, the cap’s ridge grazing the upper border, which amplifies stature. The right shoulder, pushed forward and lightly indicated, anchors the body in space, while a darker, triangular mass of fur on the left gives the lower field ballast. Rembrandt tilts the cap slightly, breaking symmetry and generating a subtle counter-curve between cap and cheek. The face lives in a clearing of bright paper, ringed by darker textures; that halo of negative space functions like breathable air around thought. This compositional clarity allows the viewer to attend to small modulations—the crease at the nose, the uneven line of the lips—without being distracted by unnecessary props.

The Velvet Cap as a Theater of Touch

Velvet is one of Rembrandt’s favorite stages for light. On the cap, parallel and cross-hatched fields alternate with smoother passages so that highlights appear as soft planes rather than glittering points. A decorative band runs across the head, punctuated by a clasp whose tiny bites give it metallic sharpness. The contrast between the cap’s plush crown and the crisp ornament articulates luxury without ostentation. Velvet here is not a costume flourish but a test of the artist’s ability to convert the sensation of nap, weight, and drape into graphic language.

The Fur Mantle and the Weight of Years

The mantle’s fur descends in dark, quiet swells that almost swallow the torso. Rembrandt renders it with strokes that bristle then subside, suggesting layers upon layers of pelt and lining. The fur has narrative weight. It protects, insulates, and dignifies, but it also seems heavy, as heavy as time. Where it meets the beard, the marks change key: the fur’s dark currents break into the beard’s lighter surf. That meeting point is one of the plate’s most eloquent edges, a seam that binds luxury to mortality.

The Architecture of the Face

Rembrandt constructs the face with an architect’s rigor and a poet’s restraint. The forehead is kept relatively open, a pale arch under the cap’s shadow; the brow ridges are set with short, sturdy lines; the nose descends in a broad plane that catches light at the bridge and sinks into tone near the tip; the cheeks are handled as curved facets where hatching turns with the form; the mouth tightens gently, the corners neither lifted nor dragged; and the beard erupts from the jaw in waves. Nothing is overdrawn. Even the eye sockets are left partially to the viewer’s completion, their darkness proportioned so the gaze seems present without theatrical sparkle. The face projects a mind at work, not a mask of generic age.

Light That Judges and Consoles

Illumination appears to arrive from high at left, glancing across the cap’s ridge, sliding down the forehead, touching the top of the cheek, and dissolving in the beard. But the light is not a stage effect. It feels like daylight shared with the viewer, diffused and honest. The brightest area is not the cap but the beard’s upper field, which acts like a reflector throwing a mild radiance back at the face. This reciprocal glow is emotionally significant: the old man is lit by what he has grown, by the time he carries. The plate’s shadows judge only in the sense that they reveal form; they do not condemn.

The Psychology of a Downward Gaze

The sitter looks slightly down and to our left. The eyes are not closed off; they are absorbed. Such a gaze shifts the portrait’s energy from presentation to inwardness. He is caught not in the act of being looked at but in the act of considering. That psychological inflection shortens the distance between subject and viewer. We do not feel inspected; we feel admitted to a space of thought. The mouth’s measured line strengthens the impression of a mind unhurried by performance.

Unknown Sitter, Known Humanity

No consensus identifies the model. He may be a studio regular, a street acquaintance, a patron, or a figure invented from memory and costume pieces. Rembrandt’s Amsterdam teemed with such faces, and he collected them. The uncertainty is a gift. Without a proper name to anchor the plate in biography, we learn to read character traits embedded in the handling of features and fabrics. The image honors the singularity of a person while standing for a larger human experience: how age gathers, how dignity sits lightly on those who do not perform it.

The Signature as a Breath in the Corner

At the upper left, the faint “Rembrandt f 1637” floats like a caught breath against the blank paper. The inscription, lightly placed, balances the cap’s mass and introduces a counter-gesture: the artist’s hand entering the composition even as it retreats. Signatures in Rembrandt rarely shout; they share the room with the sitter. Here the date links the plate to an astonishingly productive year in which the artist explored heads, biblical narratives, and domestic themes with equal intensity.

States, Plate Tone, and the Atmosphere of Printing

Impressions of this etching can vary remarkably. When plate tone is left on, the background fogs slightly, so the head emerges as if from a mild interior dusk; when the plate is wiped cleaner, the face stands in clearer air and the beard brightens. Drypoint burr can either be fresh and velvety in early pulls or worn away in later ones, changing the beard’s softness and the fur’s richness. These variations remind us that an etching is not a single image but a practice—a living instrument tuned at the press. The old man’s presence acquires different temperatures depending on that tuning.

A Conversation with Other Heads

The plate converses with Rembrandt’s many etched and drawn heads: study sheets of beggars, prophets wearing invented turbans, scholars with books, old men in profile and three-quarter. Across them, a pattern emerges. Headgear is used to crown the cranium with form and weight; beards become fields for calligraphic play; faces are presented not as social emblems but as landscapes of experience. Among these, “An Old Man, Wearing a Rich Velvet Cap” stands out for its synthesis of luxury and modesty. The cap is splendid, yet the demeanor is quiet; the fur is heavy, yet the mind is light.

The Grammar of Rembrandt’s Line

Rembrandt’s etched line is a language with nouns, verbs, and conjunctions. Long, steady hatch marks are nouns, giving names to planes of velvet and fur. Short, quick, pivoting strokes are verbs, animating hair and glints. Crosshatching serves as conjunctions, binding areas together so that value transitions feel grammatical rather than abrupt. In this plate the syntax is careful and classical. The cap reads as a paragraph with subordinate clauses of fold and sheen; the beard is a run-on sentence that never loses its rhythm; the face is a balanced period, calm and complete.

The Silence of Background

The background is a field of quiet paper that strengthens the head’s sculptural presence. Unlike later portraits that scatter props to assert profession or status, this plate exercises restraint. The emptiness is not neglect; it is ethical. It refuses to distract us from the person. In an age of mercantile display, the blank field models a different kind of wealth: attention.

Age, Time, and the Weather of the Skin

Look closely at the forehead and the crow’s-foot region at the outer eye. The lines are not caricatured; they are weather. Rembrandt lets hatching turn with the form so that age is experienced as a history written in topography, not as a symbol for decline. The cheeks do not sag theatrically. They bear the mild fullness of a face that has had time to settle into itself. The beard covers much, yet it also functions as a calendar, each curl a season recorded in hair.

Luxury and Piety Without Conflict

Dutch viewers of the 1630s navigated tensions between Calvinist sobriety and worldly success. Rembrandt’s treatment finds a balance that feels truthful. The cap and fur are rich, but the spirit inhabiting them is unpretentious. The portrait suggests a man who can own fine things without letting them speak louder than he does. That equilibrium is part of the plate’s enduring appeal; it proposes a way to be prosperous without being gaudy, venerable without being remote.

The Hand as a Quiet Parenthesis

At the lower right, the faintest suggestion of a hand brackets the composition. It barely emerges from the fur, an unobtrusive parenthesis that confirms the body’s presence and hints at an unrecorded gesture. Rembrandt often uses such abbreviations to keep attention on the head while assuring the viewer that this is not a disembodied mask. The hand is as reticent as the sitter’s expression.

Intimacy of Scale and the Social Life of Prints

The print’s intimate size matches the social rituals it anticipated: being held close, passed among friends, pasted into albums, studied by candlelight. In such settings, the old man’s near-life presence could spark conversation about character, age, prudence, and fortune. Unlike a painted portrait tied to a patron, an etching like this could circulate widely. Its democracy of access is built into the medium.

How the Image Teaches Us to Look

The portrait trains the eye to move in arcs. Begin at the clasp on the cap, follow the ridge to the left where a small highlight slips into shadow, descend across the temple to the cheek’s bright plane, drop into the beard’s turbulence, then rise again through the fur’s dark sea to the cap’s edge. That circuit reveals Rembrandt’s strategy: set up transitions between large quiet areas and small active ones so that the viewer’s attention alternates between rest and discovery. The image offers both serenity and detail-hunting, never exhausting either.

Why It Feels Contemporary

Despite costume and technique, the portrait feels remarkably present. The open background, frank lighting, and preference for economical description anticipate modern photographic sensibilities. The sitter’s unperformed interiority reads as a familiar modern virtue. It is easy to imagine this face among contemporary portraits of elders who carry authority without pomp. The plate demonstrates how an artist’s humble means can produce an image that resists dating.

A Final Quiet

After long looking, the portrait leaves a quiet behind the eyes. It does not resolve into a message. It remains a person, encountered and remembered. Rembrandt’s gift is to make a small sheet feel like a room one can re-enter. Each return discloses a new inflection—the beard a little more riverlike, the velvet a little more cloudlike, the mouth a shade more patient. The old man neither invites nor refuses judgment. He shares a presence; we supply the rest.