Image source: wikiart.org

First Encounter With Recognition At The Table

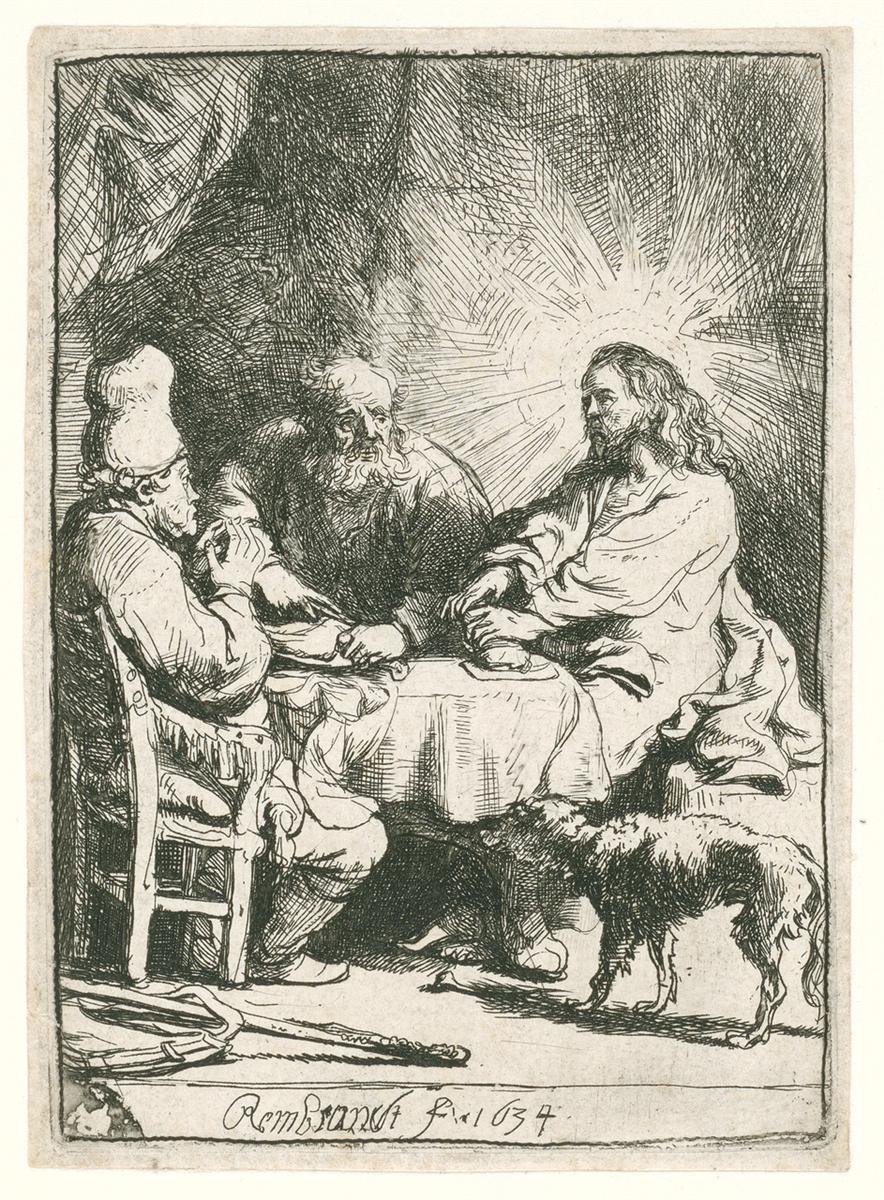

Rembrandt’s 1634 etching “Christ at Emmaus” captures the instant when ordinary supper turns into revelation. Two disciples share a simple meal with a stranger met on the road from Jerusalem. As he breaks bread, they recognize him as the risen Christ. Rembrandt compresses that seismic recognition into a candlelit room where gestures are small, faces are close, and the shock of knowing is expressed not by spectacle but by breath, posture, and light. A radiant nimbus blossoms behind Christ’s head, yet the rest of the image remains stubbornly domestic: a tablecloth creased from use, a chair with turned legs, a walking staff tossed to the floor, and even a scruffy dog nosing at someone’s heel. The drama here is interior. The print invites us to witness how understanding enters a life through the senses and settles there as certainty.

The Gospel Story And Rembrandt’s Choice Of Moment

Luke’s Gospel tells how two disciples, grief-stricken after the crucifixion, walked to Emmaus discussing all that had happened. A stranger joined them, interpreted Scripture along the way, and accepted their invitation to stay for supper. At the table he took bread, blessed, broke, and gave it; “then their eyes were opened, and they recognized him.” Rembrandt chooses precisely that hinge: the breaking of bread as recognition dawns. The disciples’ faces are turned toward the guest with varying mixtures of wonder and dawning comprehension. One sits upright, lips parted as if he has stopped mid-question. The other leans forward, his hands coming together not in formal prayer but in an involuntary brace, a human instinct for steadying oneself when reality shifts. Christ’s hands remain calm, one gathering the cloth, the other guiding the bread; the stillness of his gesture anchors the amazement around him.

A Composition Organized Around A Triangle Of Attention

The design resolves into a tight triangular arrangement. At the left, a disciple sits on a carved chair, his hat rising like a small tower and his body forming the triangle’s first vertex. Opposite him, Christ occupies the right vertex, draped in flowing fabric, his head turned gently toward his companions. Between them, slightly behind the table, the second disciple forms the apex. The three heads, linked by eye-lines to the loaf and cup, create a circuit of attention that holds the viewer inside the moment. The dog in the foreground and the walking staff fallen on the floor draw the triangle downward into lived space; they prevent the scene from becoming a floating vision. Instead, it is a table in a room, and everything that happens in it is as real as the chair’s legs and the dog’s shaggy back.

Line That Thinks Aloud

Etching is a medium that speaks in strokes, and in this print Rembrandt’s needle behaves like a mind changing gears. Broad, parallel hatchings saturate the room’s upper left, where drapery hangs and the wall recedes; the density there acts like an acoustic hush, concentrating the eye on the table’s brightness. Around the figures’ faces the lines loosen to let paper serve as skin. The tablecloth receives decisive vertical hatches that read as woven threads catching light. The dog’s fur is a scatter of quick, irregular marks, the perfect grammar for animal scruff. And behind Christ, rays of light are drawn not as solid beams but as rapidly incised bursts, some long, some short, radiating into the plate tone like memory expanding. Nothing is overworked. The vitality of the line lets the recognition feel fresh, as if etched at the speed of realization.

Chiaroscuro As Disclosure

Rembrandt’s manipulation of light and dark is never merely decorative; it dramatizes knowledge. The faces and bread share the sheet’s highest light, binding person and sign. The heavy shadow collapsed behind the central disciple sets his head in relief, making his expression legible and his surprise almost touchable. Christ’s radiance is insistent but not theatrical. The halo registers as a phenomenon inside the room’s air rather than as an imposed emblem. Its rays thin as they extend, so that the glow seems to fade into the ordinary darkness, exactly as recognition spreads from a single detail into the rest of a life. The left disciple remains half in shadow, as if his mind is still catching up to his eyes, while the dog sniffs in near-darkness, ignorant of all but smell. The chiaroscuro maps the degrees of awareness in the room.

Gesture, Bread, And The Body’s Intelligence

Hands carry the storytelling. Christ’s pose is not priestly display; it is the remembered economy of a host who has broken bread countless times. That bodily memory triggers the disciples’ recognition. The left disciple raises his hands as though to speak, then pauses; the central disciple knots his fingers together, pulled forward as if gravity has moved. The gestures are small, truthful, and persuasive. Rembrandt understands how revelation often arrivals through the body: the familiar turn of a wrist, the rhythm of a blessing, the way bread gives under the heel of a palm. Theology is enacted here as muscle memory.

Domestic Objects As Anchors Of Meaning

One of Rembrandt’s gifts is to let ordinary things carry sacred freight without losing their ordinariness. The staff on the floor is more than a prop; it is the record of a day’s journey and the sign of a pilgrim’s need. Its placement at the lower margin, loosely crossed with a strap, tells us the disciples have arrived weary and have not yet fully unpacked themselves from the road. The chair and table are stout and serviceable, not ornate; the cloth falls in unfussy folds; the loaf is round and rustic. That simplicity turns the supper into a template for every meal since. The dog’s presence, domestic and unaware, intensifies the paradox: the room is sacred precisely because it is so human.

The Psychology Of Faces

The disciples’ faces are distinct and unsentimental. The left figure’s mouth opens as if the question he was forming answers itself without words. His heavy hat underscores his earthbound practicality; he is a person who likes facts, and the fact of the bread-breaking has slipped a key into the lock of his mind. The central disciple’s eyes widen, brows lifted; his beard catches lights along a few strands, signs of a body that has leaned forward without thinking to do so. Christ’s profile is quiet and kind; his attention is not on his own radiance but on the people across the table. The scene resists the temptation to make the disciples saints in a way that would distance them. They remain recognizably human, and their humanity is exactly what makes their recognition ours.

The Halo That Behaves Like Air

Rembrandt has etched halos in different ways across his career. Here, the rays are long, thin, and uneven, some biting deeper into the copper, others barely grazed. The variability gives them a tremor that reads as light diffusing through atmosphere rather than as a rigid symbolic device. Importantly, the rays do not sever the space behind Christ. We can still feel the wall, see the cross-hatching, sense the curve of the room. The halo is less an emblem than an event, a change in the air when truth becomes visible. That subtlety saves the print from pious cliché and gives it the freshness of lived experience.

Tabletop Theology And Eucharistic Resonance

The Emmaus story has long resonated with Christian reflection on the Eucharist. Rembrandt acknowledges this without turning the scene into liturgical illustration. There is no chalice of gold, no altar. The table is an ordinary table, the bread a loaf broken in human hands. Yet the composition places bread and Christ’s hands at the center so decisively that the connection is inescapable. The disciples’ awakening passes through the breaking and giving of bread; they know him in the act of shared nourishment. The print therefore explores the way meaning inhabits matter: grace rides on grain, and revelation becomes edible.

The Dog As Counterpoint And Proof Of Everydayness

Viewers often dwell on the dog, a creature oblivious to any nimbus. Its presence does several clever things. It answers light with smell, sight with nose, theology with appetite, thereby supplying a comic, affectionate counterpoint to the disciples’ dawning awe. It also anchors the scene in domestic habit. There are no marble floors here; this is a place where animals wander in and crumbs matter. Finally, the dog’s tail, lowered and relaxed, introduces a note of trust into the foreground, suggesting that whatever is happening at the table is not danger but homecoming.

The Curtain And The Room’s Breath

At the left edge a curtain falls, densely hatched, curving inward like a stage drape. It stops the eye from bleeding off the plate while dramatizing the smallness of the room. By pressing shadow into that corner, Rembrandt inflates the table’s brightness. The curtain also invites a theatrical reading: the road scene has concluded, and now another act begins in the quiet theater of supper. But unlike a stage prop, the curtain feels domestic, its texture familiar, its weight believable. It is the kind of fabric that keeps a draft out and gathers the room’s warmth. The disciples are literally sheltered as they learn what the day’s stranger has brought them.

1634 And The Etcher At Full Confidence

This print comes from an early but confident moment in Rembrandt’s career, when his etched line had become a full instrument. He understands how few strokes are needed to define a hand, how to thicken cross-hatching without choking space, how to let plate tone suggest air. He also understands how to compact a narrative so that it unfolds in a glance yet rewards prolonged looking. The Emmaus plate is modest in size and humble in subject, but it belongs to the artist’s lifelong pursuit: to show the sacred passing through the ordinary without tearing it.

Recognition As A Human Process

One of the print’s gifts is its honesty about how recognition works. It does not hammer the disciples with shock; it eases sight into understanding through something the body knows. The strangers on the road become the host at table; the hermeneutics of Scripture become the hermeneutics of supper. Rembrandt’s figures are not mindless recipients of a miracle; they are collaborators in their own awakening. Their faces record the time it takes for a mind to say yes, and their bodies record the gentleness with which that yes arrives.

The Viewer’s Seat At The Table

The composition leaves a pocket of unoccupied space at the lower left, just beyond the staff. It is exactly where a fourth chair could sit. That emptiness is not an accident; it is an invitation. We, too, are travelers turned guests, skeptics turned students. The print sets a place for the viewer within the triangle, granting participation without forcing illusion. Our eyes trace the disciples’ eyes, our breathing sets to their tempo, and before we realize it our attention has joined theirs on the bread in Christ’s hands. The etching’s hospitality is part of its persuasion.

Why The Image Still Feels New

“Christ at Emmaus” continues to speak because it refuses bombast. It shows how a life changes in a room you can draw from memory: a table, three bodies, bread, a dog, a walking stick. The fancy devices of later religious art are absent; what remains is a way of seeing that is generous, exact, and human. In a distracted age, the print models concentration; in a suspicious age, it models recognition that arrives through something ordinary and shared. Its light does not blind; it clarifies.

Closing Reflection On Bread, Hands, And The Light That Learns Our Names

Rembrandt’s etching is quiet on purpose. It trusts that the turning of a wrist, the warmth of crust under hand, the soft shock passing through a face are enough to carry the weight of resurrection. Around a table that could belong to anyone, two friends discover that grief’s stranger is the companion they most needed. The room does not change; the seeing does. With ink, copper, and air, Rembrandt records that change so faithfully that the moment remains available to any viewer willing to sit, look, and let the ordinary become luminous.