Image source: wikiart.org

First Encounter With Quiet Light And Concentrated Thought

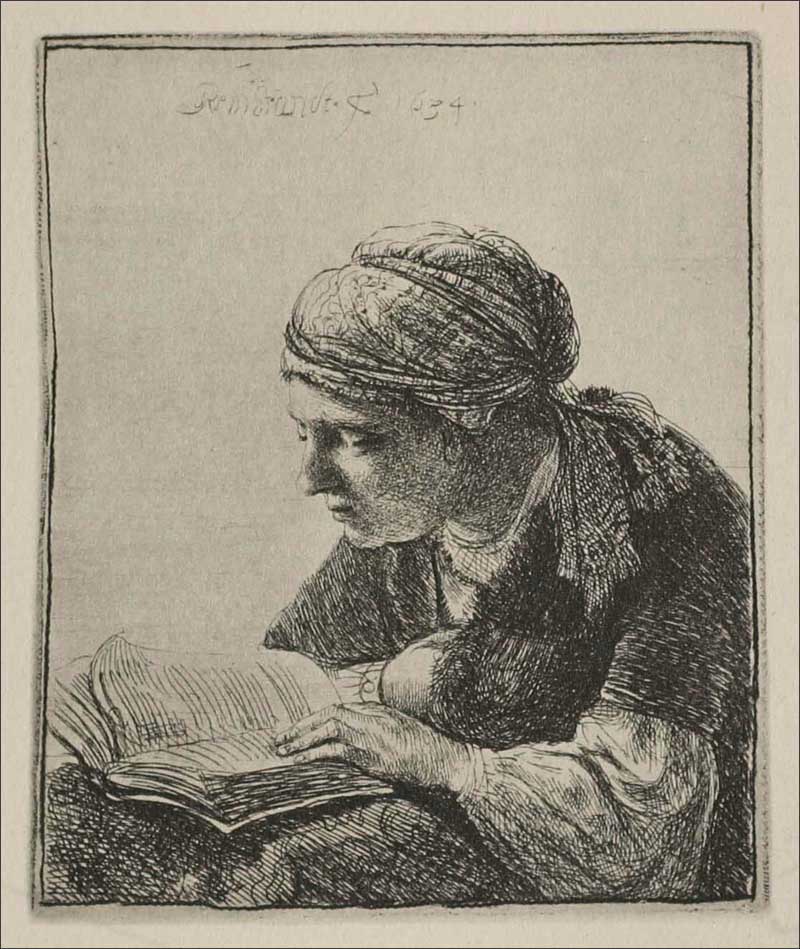

Rembrandt’s “A Young Woman Reading” from 1634 arrests the viewer with a hush that feels almost audible. The composition is small, intimate, and unassuming: a woman leans over an open book, her head wrapped in a simple turban-like cloth, sleeves rolled, body folded into the task at hand. The light is gentle rather than theatrical, settling across brow, cheek, and the ribbed planes of paper. In a century that produced grand dramas of kings and saints, this etching makes a single act—the focused reading of a book—its entire stage. The first impression is tenderness, but beneath it lies an exact, almost scientific attention to how eyes, hands, and pages collaborate when the mind is at work.

The Etching Medium As A Theater Of Whispered Detail

The sheet demonstrates why Rembrandt loved etching. Copper allows line to be both calligraphic and structural, equally capable of describing the soft nap of cloth and the crisp articulation of page edges. The burin keeps quiet; the etched needle does the speaking. Across the woman’s headscarf, the artist pulls long, hatched strokes that curve with the fabric’s wrap; across the face, he restricts himself to tight, dissolving marks that let the white of the paper become breathable skin. In the shadows under the forearm and the book’s gutter, he cross-hatches decisively, thickening darkness where weight compresses space. The plate tone—ink intentionally left on the copper before printing—creates a velvety atmosphere that tucks the figure into a soft, warming dusk. The image reads at two distances: from afar, a clear silhouette bent over a book; up close, an orchestration of tiny decisions.

A Composition That Makes Reading Visible

Rembrandt anchors the design with a strong diagonal running from the upper right shoulder through the head and down to the flare of the open pages at lower left. This diagonal is countered by the horizontal shelf of the book itself, which spreads like a shallow fan. The hands create a hinge between body and text: one steadies the volume, the other rides the near leaf, its fingertip approaching the very line the eye is tracking. The framing line near the margins is not mere decoration; it concentrates the scene like a window frame, ensuring that the viewer feels as close to the page as the reader does. Empty space above the head amplifies silence, while the dark field beneath the book grounds the scene in gravity.

Chiaroscuro As A Moral Climate

The light in this print behaves like an ethic. It does not explode in heroic shafts, but rests steadily where attention rests—face, hands, and page. The brightest values belong to skin and paper, linking person and text in a quiet alliance. Darker passages—the shoulder wrap, the hairline under the scarf, the shadowed forearm—form a kind of hushed background chorus against which the reading voice would sound. Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro is not mere spectacle; it is a philosophy: illumination belongs to what we attend to with love.

The Headscarf, Sleeves, And The Daily Majesty Of Work

Costume here is modest and contemporary: a wrapped headcloth, a simple overdress, gathered sleeves. The choice refuses allegory and establishes a world where literacy belongs to ordinary life. Rembrandt finds majesty in how fabric behaves under use. The headscarf’s ridges tighten where the cloth crosses itself; the shoulder’s wrap collapses into soft, absorbing folds; the sleeve’s crease catches small notes of light that pulse with the movement of breath. Because these surfaces are rendered with the same care as the face and hands, the sheet insists that thinking is embodied and that thought possesses its own kind of domestic grandeur.

The Face As A Map Of Concentration

The profile is understated yet exact. The brow inclines; the eyelid lowers to a thin, intent line; the mouth holds still in a gentle, neutral set. There is no smile to sweeten the scene, no furrow to dramatize it. Instead, Rembrandt registers the microphysics of reading: the slight forward reach of the neck, the delicate tension at the lower lid, the tiny economy of lips that neither speak nor press. The face is not a mask of emotion but a map of attention. The effect is moving because it is believable; anyone who has fallen into a sentence recognizes this posture.

The Hands And The Intimacy Of Turning Pages

Few artists have given hands such precise, unsentimental dignity. The left hand wedges the book open, thumb and forefinger making a small gate; the right hand extends loosely, the index finger poised over the line as if to pace the mind’s progress. The joints are squared by work, not manicured by luxury. Small highlights at the knuckles and nails supply a tactile reality that anchors the entire image. Rembrandt understands that hands are the eye’s partners; in this sheet they are co-readers, not props.

The Book As Engine Of Light

The open volume is the composition’s second protagonist. Rembrandt draws its fore-edge with a choir of parallel strokes, each leaf catching just enough ink to separate from its neighbor. The gutter deepens into shadow where the binding hides from light; the far page rolls upward in a gentle wave that traps a thin crescent of brightness along its rim. There is no title, no ornamental border, no attempt to flatter with a known text. The book is precious because it is being used. As often in Rembrandt, the tool—here a simple codex—is elevated by labor into symbol without losing its practicality.

The Psychology Of Privacy In A Public Medium

An etching is printed to be shared, yet the scene is one of deep privacy. Rembrandt resolves the paradox by placing the viewer at the same plane as the book rather than above the woman’s shoulder; we do not spy on her but sit across from her. The gaze is respectful and companionable. The border functions like a tabletop edge; the field of paper becomes shared air. Because the woman’s eyes are downcast, the viewer’s presence is both acknowledged and suspended. We are granted company without being asked to perform. The print therefore models a way of looking that protects interior life while inviting connection.

A Humanist Image In A City Of Books

Amsterdam in the 1630s was a republic of print: presses thrummed, publishers prospered, and booksellers crowded the streets near Rembrandt’s home. This image grows out of that culture without turning into advertisement or allegory. It celebrates not the commodity of the book, but the human practice of reading. The young woman is a citizen of the city’s literate commons, and the artist chooses to portray her not as a type but as a person caught mid-thought. The result is a quietly radical democratization of subject: reading, long reserved for saints and scholars, becomes an ordinary grace.

Intimations Of Identity And The Wisdom Of Not Knowing

Who is she? A servant on a pause, a merchant’s daughter, a studio model, a relative? The etching keeps the question alive without insisting on an answer. Rembrandt’s choice to anonymize the sitter allows the image to travel further. She becomes every reader we have known, including our own younger selves. The refusal to anchor the scene to a famous text or named person heightens the clarity of the act itself. The portrait is of reading, with a particular reader as its vessel.

The Gesture Of Leaning And The Ethics Of Nearness

Leaning binds body to book, world to word. In the print, the lean is slight yet decisive, a small surrender of balance in exchange for understanding. This shift carries a quiet ethic: to know something is to move toward it, to let it draw you in, to compress the world so that the page can enlarge it from within. Rembrandt immortalizes this exchange. The body’s geometry becomes a parable of attention in which proximity is not consumption but reverence.

Craft Lessons Folded Into The Image

The print is a manual for draughtsmen if one has the patience to read it. Begin with the silhouette; secure the big diagonal from shoulder to book; use plate tone to lay a fog through which light can cut; hatch along the direction of form rather than across it for fabric, and cross-hatch where weight requires depth; let the white of the paper be the brightest value for skin and page; and anchor the lower field with a dark that prevents the image from floating. Above all, let the light fall where the mind is working; everything else can soften into supportive dusk.

A Conversation With Other Reading Figures

Rembrandt etched and painted readers throughout his career: scholars bent under the lamp, saints at their desks, old men in fur caps turning pages by window-light. This young woman belongs to that lineage, but she shifts its tone. She is neither sage nor sanctified figure; she is unadorned, close, and specific. If the scholar pictures intellectual authority, and the saint pictures revelation, this print pictures comprehension. It is the unglamorous, invaluable middle in which a sentence becomes part of a life.

The Sound Of The Image And The Slowness It Invites

Although an etching is silent, this one suggests small sounds: the scratch of paper, the faint rasp of sleeve on page, the breath that lengthens at the end of a line. Those imagined sounds slow the viewer’s reading of the picture. We begin to notice how the page’s brightness pools toward the outer edge, how the headscarf’s stripes tighten near the knot, how the thumb’s nail gleams like a tiny crescent moon. The print becomes not an image to be consumed but a tempo to be kept.

Why The Image Still Feels Contemporary

The scene could live in a modern kitchen or subway: a person reading, absorbed, self-possessed. In an era bright with screens, the sheet’s physical book glows with a different sort of light—the reflection of daylight on textured paper. Yet the essential act remains unchanged. The picture’s modernity lies in its defense of concentration and in its refusal to instrumentalize the reader as “content.” She is not a model selling literacy; she is a mind at work, and that is enough.

The Ethics Of Dignity Without Drama

Rembrandt’s restraint is moral. He does not romanticize poverty or fetishize elegance; he does not ask the woman to perform femininity or piety. He grants her a dignity built from exact light and truthful posture. In doing so he crafts a counter-image to the noisy portraiture of status: here, worth is measured by the steadiness of attention. The print quietly argues that the most civilizing moments happen in rooms where no one is watching—except, now, us, invited to learn the same poise.

From Copper To Paper: The Image As Shared Object

Because the work is an etching, it was made to be multiplied and handled. Imagine small impressions passed from hand to hand, folded into portfolios, pinned to study walls. The subject of reading becomes a thing to be read, an object that builds communities of viewers who know the value of quiet. That portability gives the print its lasting cultural traction; it is not just a record of one woman’s attention, but a tool for teaching attention across time.

Closing Reflection On Light, Pages, And A Mind At Work

“A Young Woman Reading” seems simple, but its simplicity is distilled, not impoverished. Rembrandt compresses a world of decisions—about light, line, space, and ethics—into a scene so ordinary that we nearly miss its grandeur. Face, hands, and book share the highest light; fabric and air consent to a supportive hush; the composition turns leaning into meaning. We leave the print changed in a small but durable way: reminded that understanding is a bodily act, that privacy can be honored in public art, and that the most persuasive dramas can be staged on a tabletop with nothing but a book and the human need to know.