Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

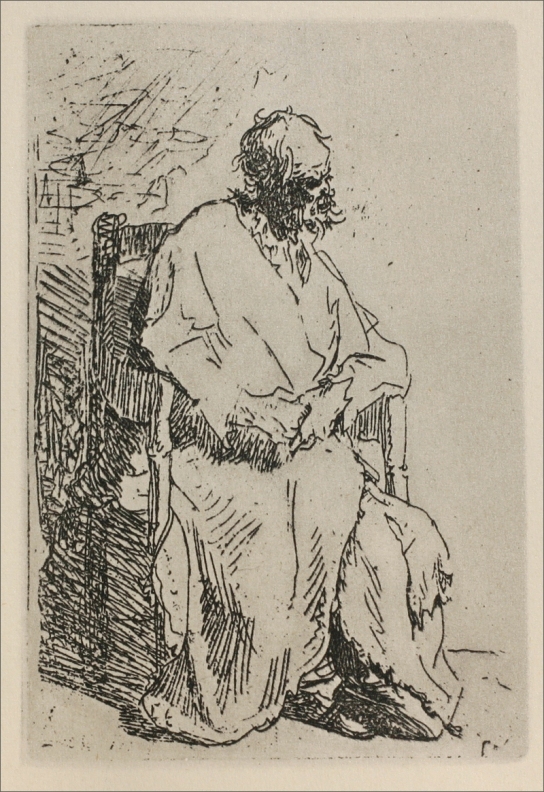

Rembrandt’s “A Beggar Sitting in an Elbow Chair” of 1630 is a small work with large ambitions. It shows a solitary, age-worn figure slumped in a chair with arms, draped in patched garments that pool around his shoes. The pose is quiet, even ceremonial, yet the spareness of the setting and the frankness of the line insist on ordinary life. Rather than a theatrical scene, we encounter a moment of simple being: a man, a chair, a bit of light carving out the folds of a robe. This sheet belongs to Rembrandt’s intense early period in Leiden when he explored the human body and face through etching, using humble subjects to test how few marks could carry maximum presence. In the beggar series he forged a new kind of image—neither moralizing emblem nor anecdotal vignette, but an unguarded study of humanity.

The Etching Medium and the Authority of Line

Although often described loosely as a drawing, “A Beggar Sitting in an Elbow Chair” is an etching, printed from a copperplate the artist covered with a wax ground and drew into with a needle before biting the exposed lines in acid. Etching suits Rembrandt’s temperament because it converts the speed of drawing into reproducible line. The medium lets him skate from feather-light scratches to dark passages where the needle has crossed the same track repeatedly. In this print, the chair’s left side is a dense hatch that anchors the composition; the beggar’s robe is expressed through long, quick, downward strokes that read as both cloth and gravity. Because etched lines preserve the hand’s pressure and rhythm, the sheet becomes a record of touch and time, a musical score of gestures that the press renders visible.

A Composition Built on Weight and Rest

The composition’s geometry is disarmingly simple. A vertical block of chair and torso occupies the left two-thirds of the plate, while an airy, nearly blank field opens to the right. The beggar’s head tips slightly forward, hands loosely clasped, legs set at an angle so the right knee projects toward us. The effect is a pyramid of weight settling into the chair. Rembrandt’s refusal to clutter the space focuses attention on the body’s relation to support: the rail under the beggar’s left arm, the chair back behind his shoulder, the seat under the pooled fabric. The realism of rest—how fabric slumps, how joints relax—is the true subject. Instead of dramatizing motion, Rembrandt reveals the eloquence of stillness.

The Chair as Character

The title draws attention to the chair, and rightly so. This is not a stool or a rough bench but an elbow chair with arms—furniture that implies a minimum of comfort and status. By placing a beggar in such a seat, Rembrandt complicates the social signal. The chair’s arms form a frame around the figure, like a portable throne, yet their etched cross-hatching is wiry and provisional, reminding us that both throne and sitter are temporary. The chair steadies the scene and deepens the paradox: here is a man socially marginal yet pictured with the poise of a seated philosopher. The chair becomes a device for dignity.

Clothing, Patches, and the Grammar of Poverty

The beggar’s garment is not narrative costume; it is a factual robe, cut wide and repaired. Rembrandt marks rents and mends with quick zigzags and short cross-hatches. Rather than mock the wearer, these signs of use humanize him. The lower hem thickens with ink where the cloth gathers on the floor, registering the drag of fabric and age. Around the neck the opening is frayed, but a soft shadow under the chin suggests warmth and breath. In this sheet poverty is not a caricature of dirt; it is a grammar of wear. The printed language of patches and folds translates a lifetime into legible marks.

The Head, the Beard, and the Refusal of Sentimentality

Rembrandt’s handling of the head is a study in restraint. He gives the beggar a tangled beard, a bald crown ringed with hair, and a profile that keeps features just shy of specificity. We recognize an individual, but we cannot name him. This balance prevents sentimentality. The artist withholds melodrama and lets the pose and the light carry feeling. The scattered short strokes around the mouth and eye read as stubble and fatigue; a darker cluster beneath the brow hints at a cast shadow that obscures the gaze. The old man seems to be looking down and inward rather than out at us, and that inwardness is the print’s quiet pathos.

Light, White Paper, and the Economy of Means

Because etching builds darkness by adding line, Rembrandt relies on the white of the paper to do most of the luminous work. The right half of the plate is scarcely touched, a luminous reserve that pushes the figure forward. On the robe, long unetched passages serve as highlights along the knees and forearms. Where he wants weight—under the seat, inside the left sleeve, behind the chair—he thickens hatching into a knit shadow. The result is a remarkably full space built with almost nothing. Light appears not as a substance poured onto the figure but as the paper itself withheld from the bite.

The Gesture of the Hands

At the heart of the composition sit the beggar’s hands, loosely interlocked. They are not imploring or dramatic; they are at rest, inhabiting the little architecture of fingers with tired familiarity. Rembrandt does not outline each finger fully; he suggests their overlap with broken contours and short hatches. This partialness is crucial. It makes the hands feel lived-in rather than diagrammed. In many of Rembrandt’s prints, hands become the place where character gathers, and here they signal composure without confidence, a humility that is neither theatrical nor abject.

Social Vision and the Dutch City

Seventeenth-century Dutch cities teemed with the poor, the elderly, and the disabled, many surviving through alms. Genre painters often included beggars as moral foils or comic relief. Rembrandt’s approach is different. He isolates the figure from anecdote and declines to stage a lesson about charity or vice. The sheet shows the fact of poverty and the persistence of personhood. By stemming the current of narrative, he allows the viewer to attend to dignity. The beggar is not a warning, nor is he a picturesque accessory; he is a subject.

Relationship to the Early Beggar Series

Around 1629–1630 Rembrandt produced a cluster of etched beggars: men and women standing, walking, leaning on sticks, asking for alms, some with children. These images functioned as tronies—studies of types and expressions—yet they also proposed a novel iconography of marginal lives worthy of close attention. “A Beggar Sitting in an Elbow Chair” stands out within the group for its stillness and its architectural calm. Where other plates lean on diagonals and street space, this one establishes an interior-like stage defined by the chair. It feels less like a street encounter and more like a studio visitation, as if the artist had invited the sitter to rest while he studied the fall of light on tired fabric.

The Ethics of Looking

To look at a beggar in art risks voyeurism. Rembrandt counters that risk by adopting an ethic of proximity without intrusion. He does not move in for a dramatic close-up of suffering. Nor does he keep the beggar at a chilly distance. The scale is conversational. The sitter seems unaware of us, which spares him the indignity of exposure, yet his body language is readable enough to foster empathy. The print teaches a way of seeing that is both exact and kind: notice the patch, the seam, the sag, but do not exaggerate them; let the person remain whole.

Technique at the Service of Quiet

Technically, the plate displays the range of etched mark available to a young master. The chair’s side is a dense weave of lines that almost becomes a drawing of texture for its own sake. The robe’s long strokes are more calligraphic, prioritizing tempo over detail. The floor beneath the shoes is a set of brief, angled touches that imply ground without insisting on it. The background receives only a flurry of diagonal scratches near the left shoulder, enough to keep the white field from feeling vacant. Each zone gets the mark it needs and no more. This economy is the secret of the print’s quiet power.

Time, Patina, and the Print as Object

Because the work exists in impressions taken from the plate, each print carries small differences of inking and pressure. Some impressions would print the darks more richly; others might preserve more of the plate tone, a thin film of ink left on the surface that warms the paper. These variations deepen the sense that the image is a living object. Even more than a painting, an etching advertises the chain of making—needle to ground to acid to press to paper—and this material history suits Rembrandt’s insistence on process as content. The beggar’s life of wear echoes in the print’s own life across impressions.

Comparisons with Later Human Studies

When we set this etching beside Rembrandt’s later studies of the aged—such as the moving drawings of his mother and the old men who populate his biblical scenes—we glimpse continuity in method and feeling. He never abandons the principle that truthfulness and mercy can coexist on paper. What changes is the amplitude. In the 1650s and 1660s the line grows freer, the shadows broader, the pathos deeper. Yet the seed of that later warmth lies here in 1630, in the careful decision to make a seated beggar neither comic nor emblematic but simply present.

Theological Undercurrents Without Preaching

Rembrandt’s culture was steeped in Protestant ideas about humility, charity, and the worth of the everyday. While the print avoids overt religious signs, it carries a spiritual undertow: the exaltation of the lowly through attention. The elbow chair evokes a seat of judgment or learning, yet here it supports one who owns little. By depicting the poor man with the composure usually reserved for scholars or saints, the artist visualizes a theology of dignity. It is not a sermon; it is a way of holding the gaze.

Why the Image Feels Modern

Part of the print’s modernity lies in its refusal to close meaning. Is the beggar dozing? Meditating? Waiting? The empty ground to the right invites us to imagine a room that could be anywhere. The chair could sit in a doorway or in a shelter, in an almshouse or a studio. Such openness prevents the viewer from locking the figure into a single story. The print behaves like a question rather than a statement, and that quality continues to feel contemporary.

Lessons in Seeing and Drawing

Artists studying this sheet can learn how to suggest mass with minimum means: let long, parallel strokes ride the grain of form; let shadows accumulate where weight settles; let the white paper perform illumination. They can also study the ethics embedded in technique: avoid caricature by interrupting outlines, signal age by softening joints rather than exaggerating them, save the densest hatch for structural anchors like chair rails. Perhaps the deepest lesson is patience. The print’s force comes not from virtuoso flourish but from cumulative, attentive work.

Reception, Market, and Circulation

Small etchings of beggars circulated widely, affordable to collectors who valued scenes of daily life. They also served Rembrandt as advertisements for his handling of light and character, previewing the empathy and observation that would animate his portraits and history paintings. Because the subject was unspectacular, the sheet’s success depended entirely on the persuasiveness of line and tone. That is precisely why it holds up so well: it stakes everything on fundamentals.

Conclusion

“A Beggar Sitting in an Elbow Chair” is one of Rembrandt’s early declarations about what images can do with almost nothing. A few lines and a field of paper summon a person with history and weight. The chair confers dignity, the robe records time, the hands speak quiet language, and the light—really the untouched paper—gives life. The result is a compact masterpiece of empathy and design. In the Dutch Golden Age, when artists competed in invention and display, Rembrandt dared to invest the humblest of subjects with monumental stillness. The beggar does not ask; he simply is, and in that being the artist locates a form of grace.