Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

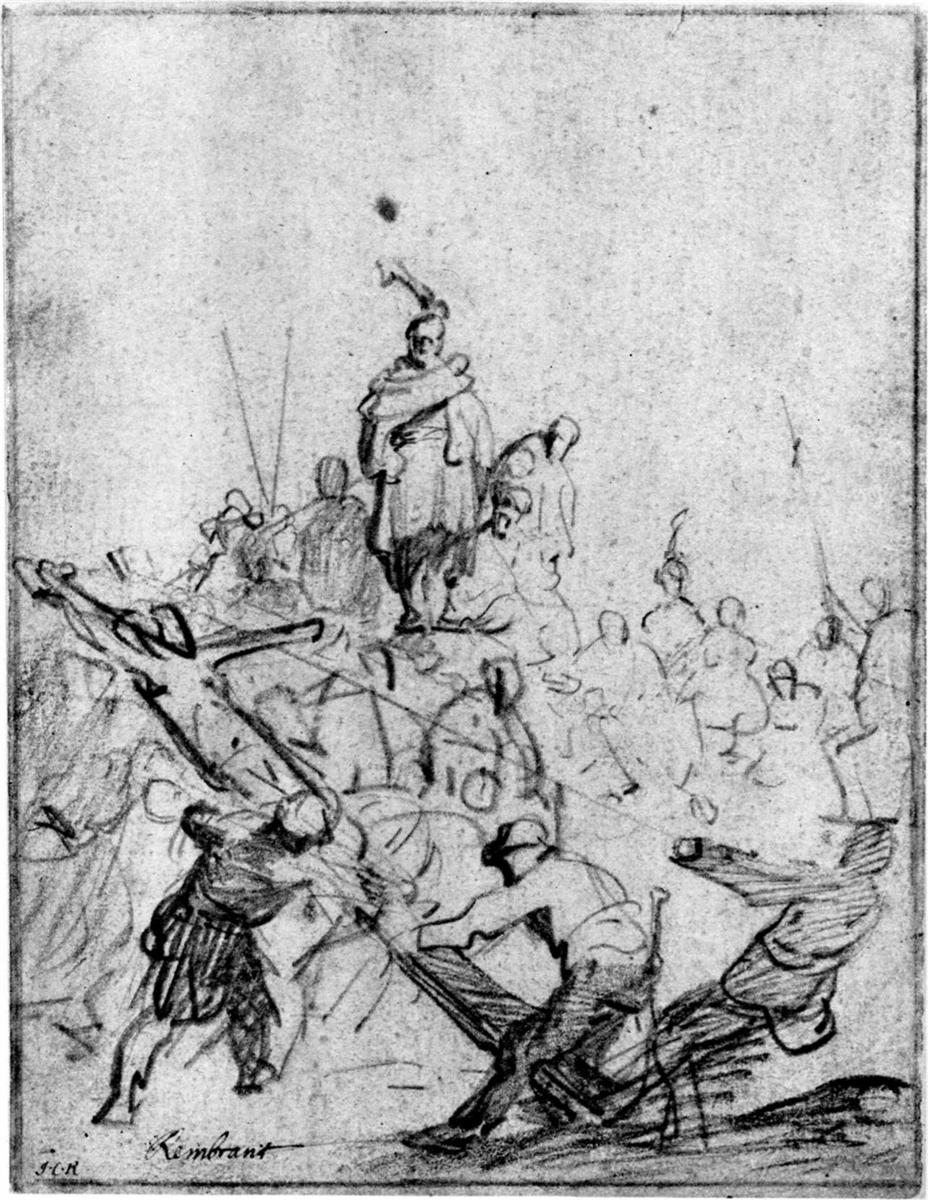

“The Raising of the Cross” (1629) is a swift, electric drawing from Rembrandt’s Leiden years that captures the crucifixion not as a finished tableau but as an act under way. Instead of presenting Christ already suspended in tragic stillness, the artist freezes the instant of collective effort that forces the cross upright. The page becomes a construction site of salvation—ropes taut, planks wedged, bodies straining, and, above the churn, a solitary figure wrapped in a mantle stands on the mound like a cool eye amid storm. With a handful of lines and pockets of rubbed tone, Rembrandt stages the Passion as labor, noise, and dust, then threads through that tumult a path of feeling that makes the scene unforgettably human.

Leiden Context And A Young Master Of Narrative

The date places the sheet at the end of Rembrandt’s formative Leiden period, when he explored small-scale histories and expressive heads with a speed and audacity that would define his career. In these years he learned to compress big stories into pocket-sized dramas where the crucial second counts more than elaborate finish. This drawing belongs to an early cluster of Passion subjects and anticipates the more elaborate painted and etched versions he would make later. It already reveals the habits that would mature in Amsterdam: a preference for the decisive moment, a dramaturgy built from diagonals and spotlit centers, and a humanism that puts ordinary workers close to the sacred action.

Composition As Engine Of Drama

The page is organized by a powerful diagonal that runs from the lower right—where two men brace a timber lever—up to the left, where the cross is being heaved toward vertical. This diagonal is crossed by shorter, counter-slanting beams, ropes, and bodies, creating a mesh of force that reads like an engineer’s diagram animated by breath. Near the center, a knot of figures pushes, pulls, and steadies; their ovals of heads and abbreviated limbs supply a rhythm of repeated forms that quickens the pace. Above them, on the crown of the hill, a wrapped figure rises into an empty sky. The broad margin of untouched paper around this figure functions as negative space that magnifies presence: stillness set against friction.

The Central Figure And The Question Of Witness

The cape-wrapped person standing high on Golgotha—head bare, a feathered plume or fluttering pennon above—has the poise of a commander or an official witness. In several Passion works Rembrandt inserts a bystander who doubles as a moral commentator and sometimes resembles the artist himself. Here the figure’s calm counterbalances the workers’ strain, and his vantage point provides the viewer a psychological bridge into the scene. We look first at him—at rest, measuring—and then down along his sightline into the tangle of labor. Authority, observation, and complicity thread through this upright silhouette, reminding us that the crucifixion was not only a theological event but also a public project overseen and seen by many.

Drawing As Theater Of Process

Rembrandt’s medium—black chalk or graphite with rubbed tone—turns the page into a rehearsal stage where decisions are visible. Some figures are declarative, their contours sealed with sure strokes; others are lightly ghosted, ideas still in motion. The cross’s timber is a thick, assertive band; the ropes are quick flicks and loops; the hillside is massed with hatching that darkens toward the bottom to anchor weight. The openness of the drawing is not a lack but a strategy. It lets viewers feel the scene as a process rather than a picture, an action that could lurch or slip at any second.

Bodies As Machines Of Force

At the lower edge, two laborers provide the most kinetic passage. One plants a foot and leans into a lever; the other crouches on the beam, pulling with both arms. Their bodies become simple machines—fulcrum, lever, torque—rendered with lines that concentrate around joints and release around limbs to imply motion. Along the left slope several men haul on ropes; the arcs of their pulls repeat, like waves striking the same shore. None of these figures is individualized; their anonymity conveys the collective nature of violence. The cross rises because many hands insist.

Spatial Depth Without Architectural Scaffold

Rembrandt builds depth without relying on detailed scenery. The foreground is darkened by heavier hatching; the middle distance is a vibrating field of mid-tone and abbreviated outlines; the far distance is almost vacant, a breath of pale paper that opens the scene to the sky. This recession keeps the eye moving and prevents the crowd from congealing. It also shifts our attention from environment to action—no city walls, no mountains, no decorative ruin—only people, wood, rope, and earth.

Light, Silence, And The Sound We Imagine

Although the sheet contains no explicit lighting model, Rembrandt’s selective darkening behaves like illumination. The lower right is weighted and noisy; the summit and sky are quiet. The contrast encourages us to imagine sound: grunts, orders, the scrape of wood, the gritty slide of the cross in its socket. At the top, around the solitary figure and the upper shaft, the silence of blank paper is almost moral—a pause in which the reality of what is happening can be felt. The drawing proves how a master can make a page hum with noise and then suddenly still it, all with degrees of pressure.

Christ’s Presence And The Ethics Of Indirection

Christ’s body is scarcely described—his small silhouette foreshortened on the timber—yet the weight of his presence is everywhere, transmitted through the work done around him. By refusing to linger over wounds or expression, Rembrandt dignifies rather than sensationalizes. He shows the crucifixion as a system of actions—tilting, hauling, bracing—whose goal is suffering. This indirection is ethical as well as aesthetic: it acknowledges that atrocity often occurs through distributed labor rather than one villainous gesture. The image is therefore about responsibility as much as it is about sacrifice.

Gesture As Narrative

Every gesture here tells a sliver of story: a man steadies a rope by wrapping it around his wrist; another, half-seated on the slope, digs in his heels; one turns his head to shout; one bends awkwardly, caught between push and pull. These micro-actions accumulate into a macro-narrative that needs no inscription. Rembrandt chooses the instant when all gestures converge—before the cross locks into its socket, before the crowd’s noise becomes a roar of triumph or horror. Suspense lives in the gap between upward striving and the inevitable fall into place.

The Crowd As Chorus

In Rembrandt’s tragedies, crowds often function like a chorus—observing, murmuring, bearing the social temperature of the scene. Here they appear as a mist of heads and shoulders, loosely indicated, their anonymity intensified by the page’s pale center. They complete the moral geometry: workers enact, authorities oversee, the crowd receives. By distributing attention among these groups, the drawing refuses a simple hero-villain schema. Instead it portrays an event that implicates many kinds of people, a complexity that deepens the pathos of the central act.

The Hill Of Golgotha As Stage

The mound itself is a character. Its ramped profile gives the cross leverage; its crumbling edge and scored shading read as loose rock and dirt kicked by boots. The summit forms a natural platform on which the solitary figure stands, and the open sky above it becomes a void that swallows detail, emphasizing how small human actors are against the space of destiny. Rembrandt shapes the hill as a stage built by the earth, perfect for this one cruel performance.

Comparisons With Later Versions

When Rembrandt later painted “The Raising of the Cross,” he famously inserted himself among the laborers, a torchlit figure helping heave the beam. This drawing already contains the seeds of that idea: the notion that artists and viewers are not just witnesses but participants, because our looking is part of the event’s perpetuation in memory. The Leiden sheet is leaner, quicker, and perhaps more radical. It dispenses with oil’s seductions and leaves only the argument of forces. In doing so, it shows how Rembrandt thinks—how he finds a scene’s spine before clothing it in color.

Anatomy Reduced To Vectors

A hallmark of the drawing is how confidently Rembrandt reduces anatomy to expressive vectors. Calves become arrows of thrust; forearms are cords of pull; shoulders are wedges that transmit force to tools. Instead of modeling every muscle, he isolates the lines that matter to the action. This economy makes the figures readable at a glance and keeps the page from clogging with description. The result is a kinetic clarity rare in religious art, where detail often stalls motion.

Theological Resonance In A Working World

By rendering the Passion as coordinated labor, Rembrandt speaks to a culture of guilds, shops, and shipyards. The men raising the cross look like the men who raised masts and hauled goods on Leiden’s quays. The analogy does not demystify the sacred; it grounds it. Salvation’s price is paid in sweat. For a Protestant viewer steeped in the dignity of work, the scene reads with immediate relevance: theology enacted in the grammar of daily toil.

The Role Of the Artist As Stage Manager

Everything in the drawing signals a mind staging action with economy. Rembrandt assigns parts—haulers, lever-men, overseer, throng—then distributes them so that motion flows from corner to corner without breaking. He keeps the top third empty to ventilate the tumult below and to give Christ’s impending elevation metaphoric air. The discipline is visible and instructive. We watch a young artist mastering the craft of directing attention.

The Emotion Of Lines Left Unfinished

Many outlines trail off; some figures dissolve into gestures. Far from feeling incomplete, the sheet draws its poignancy from this openness. Unfinished lines behave like unanswered questions—Who are these men? What will each do next?—and the viewer’s mind completes them, participating in the making. That collaboration mirrors the theme: many hands raise the cross; many eyes finish the picture.

Why The Drawing Still Feels Immediate

The sheet remains urgent because it captures an experience we recognize: a task that requires many, balanced on the edge of success or disaster. Its marks are as quick as a shouted order, its spaces as breathless as a held moment. The central stillness—one upright witness on a sky-scraped mound—keeps that urgency from chaos and converts it into meaning. The viewer leaves with the sensation of having stood where the dust flew.

Conclusion

“The Raising of the Cross” from 1629 is a compact storm of lines that turns the crucifixion into lived, physical time. Composition, gesture, and the poetics of unfinished marks carry the narrative more forcefully than any elaborate finish could. Rembrandt sets labor against authority, crowd against silence, motion against pause, and he binds them along a single diagonal that climbs toward an open sky. The drawing shows a young master discovering how to make history immediate and moral without sermonizing, and it prefigures the larger triumphs to come. In a few minutes of chalk, the mountain moves, the cross rises, and the page becomes a theater of human consequence.