Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

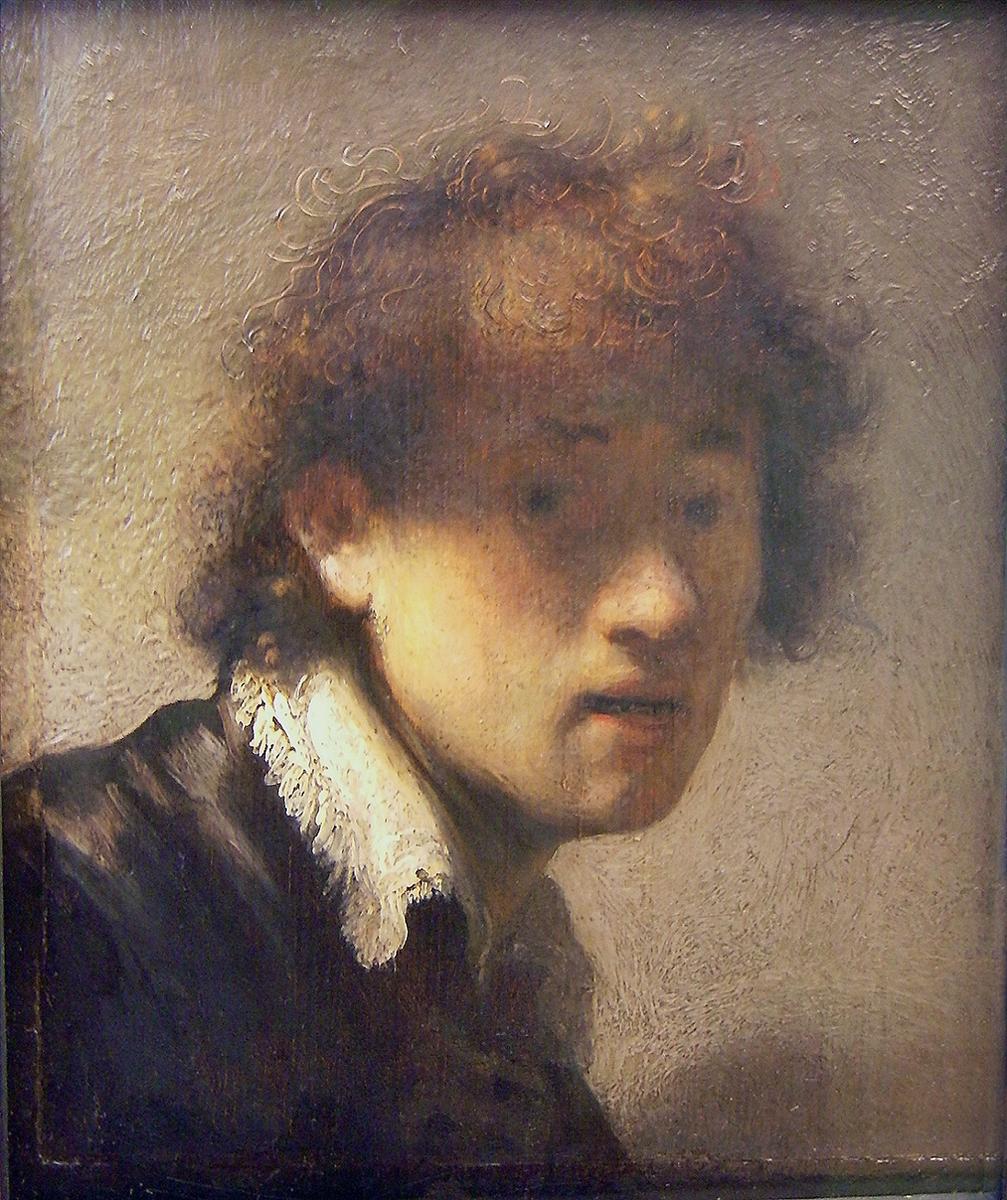

“Self-portrait at an Early Age” (1629) shows Rembrandt at roughly twenty-three, looking out from the picture plane with a startled, searching alertness that feels almost audible. The face is tilted, the lips are parted as if he has just inhaled or is about to speak, and a bright ruff flashes under the jaw like a shard of light. The hair is a halo of copper curls that catch illumination in tiny crests of paint. Against a pale, irregular ground the head advances with force, modeled by warm shadows that preserve the immediacy of a studio encounter. This is not a courtly likeness or a ceremonial declaration; it is the record of a young artist testing perception and personality with extraordinary candor. In its scale, surface, and psychological charge, the picture announces the vocabulary Rembrandt would refine over the next four decades: chiaroscuro as thought, texture as truth, and intimacy as a road to the universal.

Leiden Years And The Urgency Of Experiment

The date places the work in Rembrandt’s Leiden years, a period of intense experimentation in which he multiplied tronies, head studies, and compact dramas. Painting oneself served both practical and conceptual aims. The sitter was always available and never impatient; the model’s interior life was equally accessible. But beyond convenience, self-portraiture offered a laboratory in which the painter could probe expressions, test lighting arrangements, and explore how far the human face alone could carry narrative. This early self-portrait distills the urgency of those years. Rembrandt presents not just features but sensation: the temperature of air on skin, a breath caught midway, the pressure of light across the brow. He explores the threshold between study and finished painting, allowing the energetic touch of the studio to remain visible while achieving a resolved image.

Composition As A Theater Of Proximity

The composition shoves the visage close to us. The cropping is assertive: shoulder and collar press against the bottom edge, and the head occupies much of the field. There is little background stagecraft—no window, parapet, or symbolic attribute—to distract from the encounter. The near-distance confronts us with the ethics of looking. We are not spectators from afar; we share the artist’s air. Rembrandt builds this proximity with a few decisive diagonals: the line of the collar rising toward the jaw; the tilt of the head that aims the gaze slightly past the viewer; and the mass of hair that expands outward like a soft cloud. These angles energize the square support, keeping the image from freezing into posed stasis.

The choice of a pale ground, rather than a deep brown or black void, is crucial. Light seems to come from all around, but strongest from above left, traveling across forehead and cheek before slipping into the half-shadow that defines the mouth and chin. Against this ground the silhouette reads crisply yet gently, and the face appears to be emerging rather than positioned—an effect that heightens the sensation of immediacy.

Chiaroscuro That Thinks In Halftones

Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro in 1629 is already sophisticated, but it operates less through theatrical extremes than through intelligent halftones. The transition from lit temple to shaded cheek is not a hard border; it is a musical modulation. He interleaves warm browns and cool grays so finely that the skin seems to hold light within it. The deepest shadow collects under the lower lip and along the jaw toward the ear, lifting the mouth’s slight parting into relief. That opening between the lips is a small abyss of meaning—uncertain, vulnerable, alive. The eye sockets ride the boundary between light and darkness, so that the pupils register as dark glints rather than empty pits. This balanced chiaroscuro avoids melodrama. The face remains a field of thought, not a mask split into good and evil.

The Mouth As A Narrative Device

Few features in Rembrandt’s oeuvre speak as eloquently as the mouth in this picture. The parted lips, with a nip of brightness on the moist lower lip, create a sense of interrupted action: he was about to say something, or to breathe a surprised “oh,” when the act of painting pinned the moment in place. This micro-gesture tilts the psychology toward vulnerability and curiosity rather than self-display. It also activates the whole lower face: the chin tightens, the nasolabial fold deepens, and the cheek’s rounding reads as a physical response to breath. The choice resists the stiff, sealed-lip decorum common in formal portraiture and instead embraces the animated contingency of a living expression.

The Psychology Of The Gaze

The eyes do not lock ours aggressively; they glance slightly aside, as if looking at the reflection in a mirror or at the painting itself. That sidelong cast carries a double message: we are included in his field of awareness, but the center of his attention is the act of seeing and making. This removes the vanity often associated with early self-portraits. The image is not a bid for admiration so much as an inquiry: What does my face do under this light? How far can paint capture thinking in motion? The gaze thus implicates process. The painter is studying himself, and we are invited into that study.

Materiality And The Touch Of Paint

The surface is a feast of handling. On the lace ruff, brisk, bright touches skip across a ridged ground, suggesting minute pleats without diagramming them. In the hair, Rembrandt lets paint stand proud, curling into tiny impastos that catch and reflect illumination like metal filings. The eyebrow is little more than a cluster of brown threads, but because each thread sits at a slightly different height, they quiver under light, animating the brow. On the cheek and temple the paint thins; brushed, semi-transparent layers allow the warm ground to influence the flesh, bathing it in a living warmth.

Such material variety is not decorative; it is expressive. Thick paint where light concentrates and thin paint where shadow deepens produce a tactile hierarchy that parallels the optical one. The viewer reads texture as truth: roughness belongs to hair and lace; softness belongs to skin and air. The painting becomes a topography of experience.

Color As Warm Breath

The palette is economical but sensuous. Earth pigments—umbers, ochres, and a touch of red lake—create a harmony of warm neutrals. The most saturated notes concentrate in the lips and ears, both sites of blood flow, which keeps the face physiologically convincing. A faint coolness in the background gray and in small admixtures within the ruff counterbalances the warmth so that the whole picture breathes. This heat–cool dialogue is subtle yet essential; it keeps the head from appearing cut out and instead suspends it in an atmosphere of believable light.

Edges, Air, And The Invention Of Space

Edges in this painting are arguments about air. Where the forehead meets the ground, the boundary is decisive; where hair dissolves into the background, the edge is sifted and uncertain, like smoke mixing with air. Along the collar the edge becomes jagged and sparkling, its irregularity performing the crispness of linen. By orchestrating this variety, Rembrandt constructs a pocket of space without deploying a cast shadow or a detailed background. The face floats forward because the edges breathe; the viewer senses the thin envelope of air around the head and between the sitter and the wall.

A Young Artist’s Program

What does the painting declare about its maker’s ambitions? First, that he values the small scale as a domain of monumentality. The head fills the small panel with a force equal to that of a grand history canvas because the content is distilled and the relations among light, texture, and form are rigorously composed. Second, that he seeks a portraiture grounded in truth rather than decorum. The parted lips, slight asymmetries, and moist glints refuse idealization. Third, that he understands the expressive power of paint itself—the possibility that the way a stroke sits on the surface can communicate as much as the object it depicts. In these commitments the future Rembrandt is already present.

Dialogue With Contemporary Practices

The painting enters a field crowded with conventions: the Dutch taste for sober portraiture, the Utrecht Caravaggisti’s appetite for dramatic light, and the Northern tradition of meticulous finish. Rembrandt borrows selectively. From Caravaggesque practice he takes directional illumination, but he tempers it with a sympathetic atmosphere rather than stark voids. From Dutch portraiture he adopts frontal dignity, yet replaces social signaling with psychological immediacy. From the meticulously finished surfaces of certain contemporaries he departs decisively, allowing the facture to remain visible and evocative. The result is a quiet revolution: an image that honors tradition while rewriting it into something more intimate and modern.

The Relationship To Tronies And Expressive Studies

In the same year, Rembrandt produced expressive head studies—grimaces, open mouths, furrowed brows—likely made with the help of a mirror. Those studies, sometimes called tronies, investigate the mechanics of expression. This self-portrait shares their curiosity but refines it into a poised, inhabitable persona. The open mouth is no caricature; it is the minimal sign of life, rendered with tenderness. The painting therefore sits at a hinge between raw experiment and finished portrait, a place where Rembrandt’s later genius would often dwell: the picture is complete yet retains the pulse of the moment it was made.

Silence, Sound, And The Scene We Imagine

The image invites the viewer to imagine sound. Because the lips are parted and the breath is visible, we hear—if only in the mind—the soft intake of air and the low scrape of bristles on panel. The studio becomes present: a cool morning, a north window, the painter stepping back from the mirror, evaluating, returning with a loaded brush. This imagined soundscape heightens intimacy. Portraiture becomes less a static record than a scene unfolding, and time feels thick in the paint.

The Collar As A Device Of Light

The ruff is more than a period accessory. Positioned directly under the head, it acts as a reflector, throwing light back into the shaded underside of the jaw and preventing the face from flattening against the dark of the garment. Its broken contour also injects agitation into the lower edge of the image, echoing the unsettled energy of the expression. Rembrandt achieves all this with remarkably little information—just a cluster of white strokes, some laid thick, others dryly dragged, letting the background grain read through. The lesson is that detail is not the same as description. The mind completes what the paint only suggests.

Vulnerability And Dignity

What makes the picture moving is the balanced presence of vulnerability and dignity. Vulnerability arrives via the parted lips, the soft blur around the eyes, and the candid tilt of the head. Dignity manifests in the steadiness of the gaze, the economy of the composition, and the restraint with which sensation is handled. No prop argues for status; no costume boasts. The image trusts that human presence, fully seen, is sufficient. That trust would become an ethical core of Rembrandt’s mature portraiture, where beggars and burghers alike are treated with the same grave attention.

Anticipations Of The Lifelong Self-Portrait Cycle

This canvas is one of the earliest notes in a symphony of self-representations that extends to the end of Rembrandt’s life. Later pictures will expand the palette, thicken the paint into relief, and show the face weathered by decades. Yet the essential music—self-scrutiny illuminated by warm light—sounds here clearly. The young man is already committed to recording the self not as advertisement but as inquiry. He will continue asking the same question in different keys: how can paint translate consciousness?

Why The Painting Still Feels Contemporary

Four centuries later, the portrait’s power remains immediate because it refuses varnished decorum in favor of candor. The visible brushwork restores the making to the made; the expression acknowledges the instability of a moment; the closeness disallows passive looking. In a culture saturated with posed images, the picture’s unguarded readiness feels radical. It captures the living middle between intention and articulation—the second right before words form—and in that suspended instant it gives us a person.

Conclusion

“Self-portrait at an Early Age” is a compact manifesto in oil. It declares that the human face, illuminated with care and painted with tactile honesty, can hold drama without accessories, history without narrative, and monumentality without size. The composition pushes intimacy to the fore; the chiaroscuro thinks in halftones rather than blunt contrasts; the mouth and gaze conduct a complex music of vulnerability and poise; and the paint itself—thick here, thin there—becomes a vocabulary of sensation. Everything that would later make Rembrandt the most searching of portraitists is present in embryo. The panel glows not only with youth but with a philosophy of seeing that remains, to this day, irresistibly modern.