Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

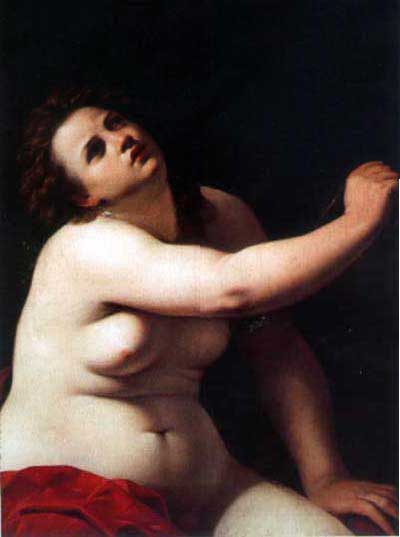

Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Cleopatra,” painted around 1620, stages a charged moment of suspension between life and death. The queen’s head tips back into the darkness, her torso illuminated by a theatrical light that reveals the warmth, weight, and vulnerability of living flesh. One arm arcs upward as if reaching for something beyond the frame, while the other steadies her on a surface we barely perceive. This is not a crowded narrative canvas with courtiers and symbols; it is a distilled confrontation with a single human body at the brink of a legendary decision. Gentileschi’s composition compresses Cleopatra’s myth into an intimate, almost claustrophobic space where physical presence, psychological intensity, and the metaphors of power and fate converge.

Historical Context

Artemisia Gentileschi emerged in Rome in the 1610s and became one of the most accomplished painters of the seventeenth century. Her art absorbed and transformed the lessons of Caravaggio: dramatic contrasts of light and dark, naturalistic bodies, and a staging sense that feels at once sculptural and theatrical. By 1620, she had already created major works in Rome and Florence, and her reputation for strong, psychologically acute heroines was well established. “Cleopatra” fits within the broader European Baroque fascination with decisive, emotionally extreme moments pulled from classical and biblical sources. Painters across Italy revisited Cleopatra’s suicide repeatedly because the subject allowed them to explore female beauty, political ruin, erotic charge, and the spectacle of death within one potent icon.

The Subject And Narrative Moment

Cleopatra VII, last queen of Ptolemaic Egypt, became a figure of inexhaustible interest for early modern Europe. After Antony’s defeat and death, ancient sources recount that Cleopatra chose suicide rather than humiliation in a Roman triumph, often by means of an asp. Gentileschi chooses a moment just before or just after the fateful bite, when resolve merges with rapture and dread. The queen’s upward tilt and slackening mouth suggest a surrender that might be spiritual, sensual, or terminal. The narrative is compressed into gesture rather than props. Instead of the snake held front and center or a tray of exotic vessels, the story is implied through Cleopatra’s exposed torso, the tense lift of her arm, and the enveloping darkness that presses toward her like the future closing in.

Composition And The Architecture Of The Figure

The entire composition pivots on Cleopatra’s body, arranged diagonally across the picture space. The diagonal is a Baroque engine; it generates motion and drama without any need for multiple actors. Cleopatra’s left shoulder serves as the fulcrum, catching the strongest light and anchoring the viewer’s vision. From this shoulder, lines travel outward along the raised arm, downward across the abdomen, and forward to the hand bracing on the unseen support. There is no background architecture or landscape to steal attention. Gentileschi uses negative space—the deep black field—to frame the curving silhouette. By eliminating distractors, she turns the human body into both subject and structure, a living architecture that carries the narrative load.

Light, Shadow, And The Tenebrist Stage

Gentileschi’s lighting is tenebrist in its starkness: a hard beam isolates Cleopatra from the darkness, modeling her with volumes rather than contour lines. The light’s angle creates crisp highlights on the forehead, cheek, and shoulder before softening over the stomach and breast, where a bloom of warmth suggests the circulation of blood beneath skin. Shadow is not simply absence; it is an active, enveloping presence that gives Cleopatra’s form its weight and its transient vulnerability. The tenebrism also renders time palpable. Light in Baroque painting often acts like a clock hand moving over a face. Here, the light has reached Cleopatra’s features and is moving on, as though we encounter her in the last bright instant before the darkness claims her.

Color And The Emotional Temperature

The palette is deliberately restrained: flesh tones that range from cool ivory to flushed rose, a wedge of red drapery, and the black void. The red is crucial because it does multiple kinds of symbolic work. It functions as a regal hue, befitting a queen whose authority once commanded a world of color and abundance. It also reads as a sign of danger and as the lifeblood that will soon be stilled. The limited palette intensifies the viewer’s sensitivity to temperature shifts on Cleopatra’s skin. Where the light hits, the color warms; where the form turns away, coolness arrives. Gentileschi’s mastery here is not chromatic spectacle but calibrated control, using minimal color to produce maximum emotional heat.

Flesh, Weight, And The Ethics Of Realism

Gentileschi paints Cleopatra with unapologetic physical truth. The soft fullness of the abdomen, the compression of skin where the body bends, and the visible heft of the breast are observed with candor. This is a queen as a living person, not an idealized marble. Seventeenth-century viewers prized such observational fidelity as a sign of painterly authority; the artist proves her skill not by sterilizing the body but by rendering its living particularity. Gentileschi’s realism carries ethical charge. By granting Cleopatra bodily credibility, she grants her interior credibility. The painting refuses to reduce the queen to allegory or ornament; she becomes a subject whose choices are earned within a world of material fact.

Gesture, Gaze, And The Psychology Of Decision

Cleopatra’s raised arm is the picture’s most enigmatic device. It might echo the motion of bringing the serpent to her breast. It might also be a gesture of appeal or a last attempt to balance herself as the body’s resources ebb. The hand does not claw the air; it floats with a controlled, nearly balletic tension, signaling resolve more than panic. The head tilts backward, eyes aspiring upward into darkness. The gaze outward is not directed at us; it passes beyond us, implying a final horizon invisible to the viewer. Such choices embed the scene in a psychological key: Cleopatra is not defeated by external force but absorbed in an internal passage from sovereignty to self-determined exit.

Iconography Without Overstatement

The absence—or near invisibility—of the serpent is deliberate. Many versions of Cleopatra’s death hinge on the asp as a visual centerpiece, but Gentileschi treats the snake as an instrument rather than a protagonist. She relocates iconography into the body’s surface: the bracelet that encircles the arm, the red drapery, and the luxuriant flesh all point toward Cleopatra’s status and toward the erotics that early modern culture projected onto her memory. By not showcasing the snake, Gentileschi avoids sensationalism and what might otherwise become a pictorial cliché. The drama is relocated to the terrain of muscles, breath, and skin, making the painting feel more intimate and modern in its restraint.

The Drapery As Stagecraft

The red drapery functions like a stage curtain both materially and metaphorically. Its thick folds catch stray light, curved forms echo Cleopatra’s curves, and the fabric’s weight emphasizes the weight of the body it partially covers. Drapery in Baroque painting often performs the task of binding a figure to the world, preventing the body from floating off into abstraction. Here it also hints at ritual—the last garment of a queen who will not wear regalia again. The drapery’s strong color patch organizes the lower left of the composition, preventing the flesh from dissolving into the dark and balancing the open, unoccupied right side into which Cleopatra reaches.

Comparisons With Contemporary Treatments

When measured against other early seventeenth-century Cleopatras, Gentileschi’s approach stands apart for its refusal of decorative excess and its insistence on bodily credibility. Guido Reni’s Cleopatras incline toward silvery idealization and courtly poise. Giovanni Baglione and others emphasize opulence, jewels, and narrative accessories. Caravaggio never gave the subject a canonical treatment, but his influence is present in the rigor of light and the prioritization of human immediacy over display. Gentileschi’s version feels closest to a private revelation. It reads like a half-length devotional picture redirected toward a classical heroine, converting the posture of a suffering saint into the self-chosen passion of a queen.

Artemisia’s Perspective And Female Agency

Gentileschi’s art has often been read through the lens of her life, and for good reason: she developed a distinctive pictorial language for women’s agency and inner resolve. In “Cleopatra,” agency does not shout; it concentrates. This queen chooses rather than is chosen for. The body is not a passive offering to the viewer; it is the site of action. The exposure of the torso is not a concession to voyeurism but an index that the decision—so often filtered through symbols—occurs in flesh. Gentileschi’s Cleopatra retains her dignity because the scene focuses on the sovereign act of ending a story on her own terms. The painter’s perspective dignifies the subject without softening the cost of that choice.

The Painting’s Place In Artemisia’s Oeuvre

Around 1620, Gentileschi’s style shows a steady control of tenebrism, a strong sense of sculptural modeling, and an interest in half-length, close-up narratives. Works from this period often isolate one or two figures against dark grounds and draw the viewer near enough to feel breath and pulse. “Cleopatra” belongs to this family of concentrated dramas. It also converses with her celebrated heroines—Judith, Susanna, Mary Magdalene—who, despite differing moral and narrative roles, share a commitment to embodied decision. Cleopatra’s tale, though classical rather than biblical, lets Gentileschi explore the same territory of conviction, endurance, and the bodily consequences of choice.

Pictorial Time And The Threshold Of Death

Baroque painting frequently arrests time at a turning point. “Cleopatra” crystallizes not the bite’s spectacle but the moment of passing when the body senses itself slipping away. The slackening of the lower lip, the easing of the abdominal muscles, and the subtle release in the raised wrist all stage a body beginning to drift from the demands of gravity. Yet the hand on the support insists that Cleopatra still belongs to the world of weight. The painting therefore holds two temporalities in friction: the earthly time of posture and balance, and the mythic time of destiny fulfilled. This dual time makes the image feel both immediate and monumental.

Sensuality, Death, And Early Modern Taste

Early modern viewers were fascinated by scenes where beauty meets death. The subject allowed painters to test how far aesthetic pleasure could be pushed in the presence of mortal gravity. Gentileschi calibrates this balance carefully. Cleopatra’s nudity is frank but not decorative; the modeling of form is sensuous without indulgence. The painting does not moralize in a didactic way, yet it does not glamorize despair. Instead, it acknowledges desire, power, and mortality as coexisting elements in a single human experience. This delicate balance explains the subject’s enduring appeal and Gentileschi’s success in renewing it without resorting to spectacle.

Material Presence And The Viewer’s Body

Looking at “Cleopatra” is a bodily experience. The viewer’s eye rises and falls with the forms the way a hand might trace the shoulder’s round or the forearm’s taut line. The scale and proximity activate empathy not through narrative cues but through corporeal recognition. We feel the stretch in the neck, the openness of the chest to air, the soft give of skin where the torso bends. Gentileschi solicits a mode of viewing in which understanding occurs as much in the nervous system as in the intellect. This viewerly embodiment mirrors Cleopatra’s own embodied agency, aligning beholder and subject within a shared field of physical knowledge.

The Drama Of The Unseen

What lies just outside the frame animates the painting. We cannot see the asp clearly or the surface Cleopatra sits upon, nor do we see attendants, chamber, or the Roman world pressing at the door. Their absence turns into presence by suggestion. The dark surrounding becomes the atmosphere of all that is not shown: empire, defeat, rumor, memory. Gentileschi trusts the viewer to supply these elements and thereby enrolls the imagination as a collaborator. The drama of the unseen is a hallmark of mature Baroque storytelling, and here it functions with particular economy. The fewer the nouns we see, the more verbs we feel.

Provenance, Replications, And Variants

Cleopatra was a subject Gentileschi revisited in variants during the late 1610s and early 1620s, a sign of market demand and of the painter’s fascination with the theme. Versions differ in the prominence of the serpent, the angle of the head, and the extent of drapery. The repetition should not be read as formula but as inquiry. Each attempt recalibrates the balance between eros and thanatos, intimacy and display. The 1620 dating places this canvas within a decisive phase as Artemisia consolidated her identity as an independent master who could deliver both narrative authority and sensuous, credible humanity.

Legacy And Modern Resonance

Modern audiences often recognize in Gentileschi’s Cleopatra a refusal to caricature powerful women. Instead of rendering the queen as a tale about seduction or political scheming, the painting insists on psychological interiority. It speaks to contemporary viewers alert to questions of agency, representation, and the politics of the gaze. The work also demonstrates how historical subjects can be made to feel urgent without anachronism. By translating a famous episode into a close, bodily encounter, Gentileschi preserves historical distance while opening a channel to present experience. The painting’s quiet boldness—its choice to do more with less—continues to influence how artists and viewers conceive the portrayal of decisive human acts.

Conclusion

“Cleopatra” creates a theater of one where light, flesh, and gesture are the only actors needed to stage the end of a queen’s life and the culmination of her will. Gentileschi’s choices reject decorative digression in favor of concentration: the frame tightens, the light narrows, the palette contracts, and the drama deepens. What remains is a portrait of agency in the first person, expressed not in words or symbols but through the body’s eloquence at a final threshold. The painting offers no spectacle of conquest and no moral lecture. It offers a human being, resolved and vulnerable, seen by an artist who trusted the truth of the body to carry the weight of myth. In that trust lies the canvas’s enduring power.