Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

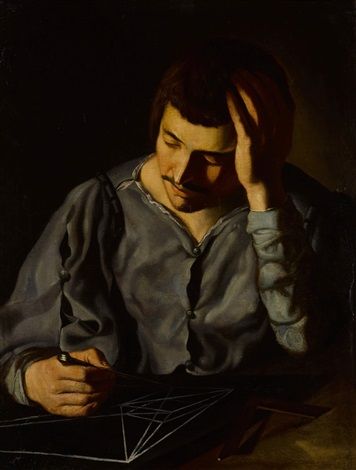

Caravaggio’s “Archimedes Drawing a Geometric Shape” is a luminous meditation on thought made visible. The composition presents a solitary figure in a gray-blue doublet seated at a table, head bowed, one hand pressing lightly to his temple while the other traces crisp white lines across a dark slate. A single beam of light cuts diagonally from the upper left and stops where it is needed most—on the mathematician’s brow, wrist, and the chalked diagram that seems to glow from the table’s surface. The rest is a hush of shadow. There is no architectural backdrop, no courtly spectators, no trophies of learning scattered about. Caravaggio distills the entire drama of discovery to a face, a hand, and a set of lines. It is a picture about concentration, patience, and the moment when an idea passes from the mind into the world.

Caravaggio’s Humanist Subject Seen Through a Baroque Lens

Portraying Archimedes, the ancient geometer famed for clarity and rigor, might invite high classicism—marble columns, bronze compasses, a page holding tablets. Caravaggio refuses that apparatus. He translates the humanist subject into Baroque immediacy by clearing the stage and placing the figure at arm’s length. The philosopher is not an emblem upon a dais; he is a worker at his desk. This choice aligns Archimedes with the artisans, musicians, cardsharps, and saints that populate Caravaggio’s world. Thought, like faith or labor, happens in a body, in a room, at a table. The painter’s realism makes the ancient genius feel contemporaneous, as if he just slipped off Rome’s streets and sat down to think.

Composition and the Geometry of Attention

The composition is quietly radical. Caravaggio designs it as a triangle within triangles. The bowed head, the hand at the brow, and the chalked lines on the slate form the main triangular cluster that holds our attention. Within the slate, the diagram—a web of straight segments intersecting at acute and obtuse angles—echoes that geometry with a stricter, crystalline precision. The hand holding the stylus becomes the hinge between body and diagram, the fleshly instrument that translates interior reasoning into exterior form. The other hand, splayed lightly against the temple, closes the circuit: mind, hand, and line create a loop of energy. Nothing in the painting breaks that loop. The gaze of the viewer is recruited to follow it, traveling from the thinker’s brow to the chalked edge, back to the wrist, and up again to the face.

Tenebrism as a Philosophy of Seeing

Caravaggio’s tenebrism—his signature orchestration of light and dark—serves an intellectual purpose here. Light is not merely illumination; it is demonstration. It shows the world the exact forms that matter: the planes of the face where thought concentrates, the sleeve that bunches as muscle controls the stylus, and the diagram where the idea stabilizes. Everything else retreats into a respectful obscurity. Shadow becomes the ground of attention, the negative space against which clarity emerges. In a painting about geometry, this control of visibility enacts a philosophy of seeing: truth appears when distractions are subtracted and a few selected relationships are allowed to shine.

The Face and the Psychology of Silent Insight

The mathematician’s expression is the painting’s emotional core. He is not ecstatic, not suffering, not posing for glory. His mouth softens into a faint inward smile; the eyelids droop with the weight of sustained looking; the pressed hand implies the mild fatigue that accompanies difficult understanding. Caravaggio captures the mental atmosphere of work—the quiet joy of a problem that is finally yielding, or the serene absorption that precedes a breakthrough. It is a psychology that viewers who write, carve, program, or practice music will recognize immediately. The painter honors intellectual labor as an embodied, time-bound, humane endeavor.

The Hands as the Grammar of Thought

Caravaggio often writes meaning through hands. Here, the left hand steadies the temple, a gesture as old as attention itself. The right hand anchors the stylus with the delicacy of a musician’s bow, the wrist turned so that chalk can glide along a predetermined path. Fingers and thumb create a small architecture of control, a counterpoint to the large architecture of the geometric figure. The hands communicate without theatrics: ideas require touch; truth is traced, not merely imagined. The way the sleeve creases under tension amplifies that message. Thought leaves weight in fabric.

The Diagram as Character

In most portraits of scholars, diagrams are props. In Caravaggio’s painting, the diagram behaves like a character. Crisp, chalk-white, and decisively angled, it shares the light that falls on the face. We do not need to know which theorem is being proved to sense its authority. The lines converge and cross with persuasive inevitability; they carry the poise of a statement about to be spoken. By giving the diagram the same visual dignity as the head and hands, Caravaggio declares that thinking is not complete until it takes shape outside the thinker. The chalked form is the work’s visible conscience.

Garment, Color, and the Material World of Study

The scholar’s garment is rendered in gray-blue, neither luxurious nor ragged, with laces at the shoulder and soft cuffs that catch spare highlights. The color has a calm, winter light quality, an ideal counterweight to the near-black surroundings and the bright white of the chalk. Caravaggio’s palette is intentionally limited to let value contrasts carry the drama. The subdued fabric speaks of utility rather than status, aligning Archimedes with craftsmen at their benches. In this world, knowledge is not costumed in velvet; it sits in cloth that forgives chalk dust.

Space, Scale, and the Viewer’s Desk

The stage is shallow. A sliver of tabletop and a void of darkness are all the setting we receive. The effect is to compress distance until the viewer feels seated at the same desk. The stylus hovers only inches from our side of the picture plane; the white lines on the slate read like marks we could smudge with a fingertip. Caravaggio’s control of scale pulls us into companionship with the thinker. We are not peering at a monument; we are sharing a moment. In a chapel or a study, this intimacy would have converted viewers into students by simple proximity.

The Ethics of Caravaggio’s Realism

Caravaggio’s realism is famous for its unvarnished candor—grimy fingernails, patched sleeves, the unposed truth of faces. Here that ethic sanctifies intellectual work. By resisting idealization, he shows study as within reach of ordinary people. The genius at the table is not remote; he is a human being in lamplight. The democratic implication is clear: clarity does not require opulence; it requires attention. Caravaggio’s choice thus aligns the authority of mathematics with the dignity of the street and the workshop.

Time Suspended: The Second Before the Line Connects

The painter is a master of narrative pauses. He habitually chooses the fraction of a second before a decisive action: a coin counted, a sword drawn, a revelation dawning. In this painting the stylus seems poised to complete a line. That microscopic suspense lends the scene its electricity. The viewer feels the mental momentum pushing toward resolution. It is the instant when comprehension and execution meet—when the mind’s path and the chalk’s path become the same.

Dialogue with Earlier Images of Archimedes

Earlier Renaissance images of Archimedes often embed the figure within a grand setting or dramatize his death during the Roman sack of Syracuse. Caravaggio avoids both. He neither stages tragedy nor arranges intellectual pageant. Instead, he gives us the man as maker of lines. This reorientation is historically savvy—the ancient sources celebrate Archimedes’ theorems and mechanical ingenuity—but it is also pictorially shrewd: a single head bent over a slate can carry more truth than a crowd. In reducing the legend, Caravaggio increases the humanity.

Light as Metaphor for Demonstration

In a painting about geometry, light naturally behaves like a metaphor for demonstration. The beam that falls across the table could be read as the proof itself, clarifying the steps one by one. The sharpest highlight lands on the chalked segments, the very places where the argument’s shape becomes visible. From there, illumination climbs to the face—the place of interior sight—and then dwindles into the darkness that stands for the unsolved remainder of the world. It is a visual syllogism: external clarity sustains internal understanding, which in turn throws light back upon the world.

The Quiet Heroism of Study

Caravaggio’s saints often display courage in the face of violence; his Archimedes displays courage in the face of complexity. The heroism here is not martial but mental—the willingness to remain with the problem, to hold the stylus steady, to return again to a line until it is right. The bowed head and the pressed hand acknowledge the cost of attention. Yet the faint curve of the mouth hints at reward: understanding gives pleasure. The painting teaches a virtue central to creative life—steady, embodied perseverance.

The Diagram’s Possible Meanings

The chalked figure invites conjecture. One sees intersecting triangles and perhaps the scaffold of a perspective construction. Whatever its exact content, the form signals relationships—ratios, angles, the elegant logic of lines arranged to prove something that could not be seen before the proof. Caravaggio, who routinely constructed his compositions from strict directional geometries, surely delighted in giving geometry a cameo as protagonist. The painting becomes self-referential: the diagram that Archimedes draws mirrors the compositional triangles that hold his body. Art and mathematics share a grammar of clarity.

Silence, Solitude, and the Conditions for Insight

The cavernous background is more than absence. It stages the solitude required for sustained thinking. No students interrupt, no patrons hover, no windows distract with landscape. The only sound we can imagine is the faint scrape of chalk. Caravaggio was himself a creature of crowded cities, but he understood the value of silence for seeing. By carving a pocket of stillness around the figure, he allows viewers to experience the same mental quiet. The painting becomes an instrument of hush.

Material Details that Persuade

Caravaggio’s credibility rests on small truths: the slight glisten along the chalk edge that catches light, the rucked seam at the shoulder where fabric strains, the tiny shadow cast by the stylus across the slate. These details work like axioms; they are self-evident and grant the rest of the argument its force. Because we believe the sleeve and the chalk, we believe the thought. The painter’s exactitude thus performs the same work that good reasoning does: it compels assent by fidelity to the real.

A Portrait of Mind for All Disciplines

Though the subject is Archimedes, the painting speaks to more than mathematicians. Writers see the pause before a sentence lands; musicians, the breath between phrases; engineers, the check before a cut. The image honors any craft that requires a mind to govern a hand in pursuit of a clear result. Caravaggio’s choice to universalize the setting—no Greek inscriptions, no civic emblems—ensures that the picture functions as a general portrait of concentration. The name “Archimedes” is an honorific for the human practice of thinking well.

Resonance for Contemporary Viewers

Modern life scatters attention; this canvas gathers it. Viewers used to screens and speed discover here the pleasure of a single task done deeply. The painting suggests a counter-ethic: clarity as beauty, patience as power, simplicity as strength. It models a studio discipline welcome in classrooms, labs, and offices—a commitment to step into a small ring of light and work there until the line is true.

Conclusion

“Archimedes Drawing a Geometric Shape” is Caravaggio’s hymn to intellect. With a restricted palette, a disciplined beam of light, and the most human of gestures—a hand steadying a brow, a hand guiding a tool—he renders the invisible labor of thought visible. The painting teaches that ideas are born in rooms, on tables, under lamps, in bodies. It celebrates the elegance of lines and the humility of the person who draws them. In the quiet between intention and mark, Caravaggio finds a grandeur equal to his most dramatic altarpieces. The hero here is attention, and the miracle is a proof carried intact from mind to world.