Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

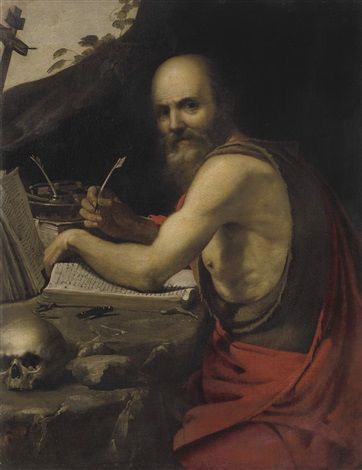

Caravaggio’s “Saint Jerome” presents the Doctor of the Church at work, poised between contemplation and composition. The half-nude ascetic sits at a rough stone desk draped with red cloth, quill in hand, turning from his manuscript to meet our gaze. A skull rests in the foreground, a cross rises in shadow, and a scatter of books surrounds the scholar like a rugged library. The setting is a cave-like retreat rather than a furnished study, emphasizing the radical poverty Jerome chose while translating Scripture and wrestling with language. Caravaggio builds the painting out of sharp light and engulfing dark, reducing the whole drama to skin, bone, paper, and wood. The result is a portrait of mind and body working together, a vision of study as devotion.

The Saint and His Story

Jerome, the fourth-century hermit and scholar, is famous for producing the Latin Vulgate and for an uncompromising temperament that matched his fierce intellect. Artists across the Renaissance loved him because his life blended the picturesque austerity of the desert hermit with the humanist prestige of books and learning. Caravaggio’s treatment belongs to that tradition, yet it strips away classical decoration. Instead of gilded lecterns or architectural vistas, we see a man of sinew and resolve, draped in a simple red mantle, surrounded by necessary tools: quills, inkwell, folios, a small wooden cross. The emphasis is on labor—writing, revising, praying—rather than on the status of a learned cleric.

Composition and the Diagonal of Attention

The composition hinges on a decisive diagonal that runs from the skull at lower left through the manuscript and the saint’s tensed forearm to the face that turns toward us. This line guides the eye along the path of thought: mortality recognized, text consulted, action taken, self examined. Jerome’s torso forms a counter-diagonal, a muscular arc that balances the page’s rectangle and keeps the figure locked into the stone workspace. The arm holding the pen is foreshortened with crisp clarity, so the quill seems to project into our space, inviting us to witness the moment when a sentence is about to be written. Caravaggio pulls the figure close to the picture plane; nothing intervenes between viewer and saint except the edge of the desk, which reads like the stage lip of a small theater of thought.

Tenebrism as Spiritual Architecture

Caravaggio’s tenebrism is not mere style: it is the architecture of the scene. A beam of light from the upper left chisels Jerome out of darkness, striking bald head, shoulder, ribcage, and forearm before glazing the pages with a soft sheen. Everything beyond this path of illumination—cave wall, foliage, the farther stack of books—dissolves into warm shadow. Darkness is never empty in Caravaggio; it behaves like silence in music, framing the notes so they can be heard. Here it functions as solitude, the contemplative enclosure within which the saint’s mind can work. The cross, placed in that penumbra, suggests that the light that falls on Jerome is also grace, visiting the place where labor and prayer meet.

Flesh, Age, and the Discipline of the Body

Jerome’s body is rendered with frankness. The exposed torso is lean, the skin stretched across ribs and shoulder, the arm taut with sinew as it guides the pen. Caravaggio refuses the soft idealization common in earlier depictions. This is an older man who has not spared himself. The physiognomy carries the history of fasting, travel, and relentless study. By giving the saint a body that works, the painter dignifies the physical effort demanded by scholarship. Thought is not airy; it requires muscle. The red mantle pools around the lap like a banked flame, a chromatic sign of ardor warming the austerity of bone and paper.

The Red Mantle and the Color of Zeal

Caravaggio uses a restrained palette—earths, grays, the pale cream of paper and bone—against which the saint’s red mantle erupts. The color serves several roles at once. It marks Jerome’s spiritual energy, the passionate intensity that drove his translations and polemics. It binds the figure visually to the crucifix in the shadows and to the stains of ink on the table, making a triad of sacrifice, word, and action. And it anchors the composition, pulling the eye back from the surrounding dark. Red in Caravaggio is never incidental; here it is the temperature of vocation.

The Skull, the Cross, and the Hour of the Page

Objects in Caravaggio’s paintings are never idle. The skull in the foreground is a memento mori, but it is also a teacher: it sits at the edge of the desk where a reader might rest his hand, insisting that every line be written under the sign of finitude. The small wooden cross, nestled in shadow at the upper left, gives the skull its answer—death judged and transformed. Between them lies the open book. Jerome’s task occurs “between”: between death and redemption, between silence and speech, between wilderness and civilization. The objects create a simple theology of the workspace, converting stones and wood into sacraments of attention.

Books, Quill, and the Craft of Translation

Caravaggio lavishes care on the tools of the scribe. The folios are thick, their pages slightly buckled as if humidity and use had shaped them; the bindings are plain, consistent with the poverty of the setting. The quill in Jerome’s hand is caught at the second before it bites the page, while a spare quill waits near the inkwell, a practical redundancy. Such exactness situates the painting not in abstraction but in craft. Translation here is manual—ink, feather, hand pressure, the angle of wrist and elbow. The saint’s sanctity lies as much in the discipline of these mechanics as in lofty intent.

Gesture as Grammar

Caravaggio composes meaning through gesture. Jerome’s left hand braces the book open; the right hand holds the quill, lifted for a heartbeat while the mind considers the next word. The head turns toward us, not defensive but measuring, as if to ask whether we understand the seriousness of the work. The slight smile—or is it a tightening?—at the corner of the mouth complicates the psychology: this is a man who knows controversy and the satisfaction of argument won, yet who has turned toward prayer often enough to soften triumph into resolve. The gestures are quiet, but the narrative is active: the sentence will land; the page will darken.

Space, Depth, and the Cave of Mind

The setting has minimal depth. A tree trunk and rock wall create a shallow grotto that functions like the interior of a skull. Within this “head-space,” books and bones arrange themselves like thoughts. Caravaggio’s decision to compress the stage intensifies involvement; we are seated almost at the same table as the saint. The only distance is temporal: the second between the raised quill and the stroke to come. In that fragile pause the painting lives.

Dialogue with Caravaggio’s Other Jeromes

Caravaggio returned to the subject of Jerome at least once more in his career, and the differences help define this version’s character. Where another canvas shows the saint writing with ascetic severity, this painting leans into engagement: the saint looks at us. The torso rotates; the quill points outward; the smile glints. It is an image of invitation rather than withdrawal. If the other Jerome is absorption, this one is address. Both share the material realism—heavy cloth, stark light—but the present picture turns the hermit into a teacher who welcomes interruption.

The Viewer as Student

Because the saint meets our gaze, we are drafted into the scene. The portrait becomes a live lesson in how to read and write under the sign of faith. The skull reminds us to use our hours well; the crucifix anchors interpretation in charity rather than mere correctness; the red mantle recalls that zeal without love becomes noise. The painting’s didactic function is subtle but real. It does not sermonize; it models a discipline. In a chapel or study, such an image would have formed its viewer by daily exposure.

The Psychology of Work

Many sacred images romanticize ecstasy; Caravaggio dignifies concentration. Jerome’s expression is alert, slightly amused, entirely intent. He embodies the intellectual joy of solving a problem—the discovery of a better Latin verb, the correction of a scribal error, the fit of rhythm in a sentence meant to be read aloud. The raised quill marks that moment when insight has arrived and hand waits to catch it. This psychology of work—humble, repetitive, luminous in flashes—makes the painting feel modern. Artists, scholars, and craftspeople recognize themselves in Jerome’s posture.

Theological Resonances in Light and Flesh

Light in Caravaggio often reads as grace offered to bodies—fallen, finite, beloved. Here it polishes the skull without macabre emphasis, warms the saint’s shoulder without flattery, and makes the page legible. The union of light and flesh signals the Christian claim Jerome’s translation would spread: the Word becomes flesh so that human words might carry glory. By letting illumination articulate muscles and manuscripts alike, the painter hints that study and sanctity are not opposites but collaborators.

Technique and Surface

The painting’s surface reveals a confident economy. Broad, thinly painted shadows preserve the breath of the ground, while the lit passages carry denser paint that holds shape under the raking beam. The red mantle is built with long ridges that turn cloth into sculptural folds; the skull gleams with small, well-placed highlights along brow and cheekbone; the books’ pages are handled with soft, horizontal strokes that mimic paper grain. Caravaggio never fusses. He paints only what the eye must have to complete the illusion, trusting light to do the rest. That trust produces freshness—an impression that the scene is unfolding rather than staged.

Comparison with Humanist Portraiture

Where earlier humanist portraits often surround a scholar with architectural grandeur and encyclopedic props, Caravaggio chooses austerity. The effect is to democratize learning: Jerome’s authority does not depend on marble and gold but on attention and labor. The saint’s body, old and strong, is the primary “architecture.” The desk is a stone slab; the library fits under an arm. This humility is not anti-intellectual; it is a claim that truth can be sought with simple means, that sanctity and scholarship thrive best in rooms where there is more light than ornament.

Time, Mortality, and the Page That Outlasts Us

The skull in the foreground and the torn edges of the pages share a dialogue about time. Flesh will fail; paper frays; ink fades; and yet words can carry memory across centuries. Jerome is caught writing for readers he will never meet. Caravaggio’s staging—saint at left, skull at right, book in between—turns that vocation into a geometry: life and death speak through the medium of text. The painting aligns the viewer with those future readers. We are the ones for whom the page is written, the ones responsible for reading with the same mixture of rigor and devotion that created it.

Why the Painting Endures

The picture endures because it shows a saint doing something ordinary with extraordinary care. It marries the drama of Caravaggio’s light to the quiet heroism of study. It rescues learning from vanity and asceticism from gloom by giving both a human face and a working hand. In the hermit’s cave we recognize our own desk; in the skull our own deadline; in the red cloth our own glints of zeal. The image suggests that holiness does not always look like rapture; it often looks like a person returning to the sentence until it tells the truth.

Conclusion

“Saint Jerome” is one of Caravaggio’s most persuasive conversions of scholarship into devotion. With a few objects—a skull, a cross, a handful of books—and a beam of light that travels from flesh to page, the painter constructs a theology of work. The saint’s body is disciplined but not idealized; the red mantle burns without extravagance; the cave is poor and sufficient. Most of all, the raised quill and turning gaze invite us to share the moment when thought becomes word. In that invitation lies the painting’s enduring power: it asks us to join Jerome in the difficult joy of attention, to read and write as if our hours mattered, and to let light make our work legible.