Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

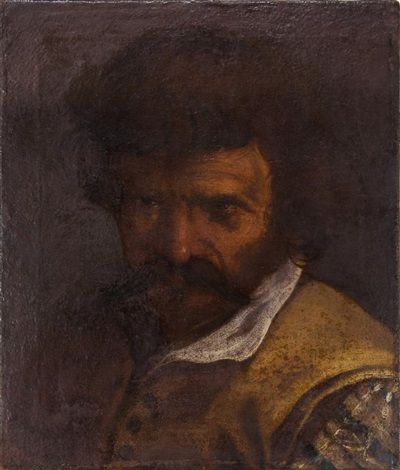

Caravaggio’s “Portrait of a Gentleman” is a small, dark, and disarmingly direct image that condenses the artist’s genius for presence into a head and shoulders. With date unknown and sitter unidentified, the painting lives in the penumbra of attribution and biography, yet it carries unmistakable traits: a face modeled by concentrated light, a background that collapses into shadow, and a psychological temperature that hovers between vigilance and fatigue. The man’s coarse hair throws a deep, ragged halo; his mustache and beard cut the mouth into a stern line; the eyes—set under a heavy brow—regard us with a wary intelligence. Nothing distracts. Costume is summarized, background withheld, and all storytelling ceded to the topography of the face. It is the kind of picture Caravaggio liked to make when he wanted the truth of a person to speak without ceremony.

The Poetics of Tenebrism in an Intimate Key

The first encounter with the portrait is with its darkness. Caravaggio uses tenebrism not as theatrical shock but as a quiet instrument: it trims away everything that would compete with the head. The background reads as an indeterminate brown-black field, mottled and breathable rather than flat. Into this darkness the face advances like an apparition of bone and blood. Light falls from high left, catching the cheekbone, the bridge of the nose, the ridge of the brow, and the roll of the collar. The right side of the face is allowed to fade, not abruptly but through a sequence of warm half-tones that keep the skin alive inside shadow. This handling is crucial: the viewer’s eye remains engaged in subtle gradations rather than blunt contrasts, a sign of a painter interested in proximity rather than spectacle.

Format, Scale, and the Ethics of Nearness

Everything about the painting’s format argues for nearness. The head nearly touches the upper border; the shoulders are cut just where the collar lifts; there is no air for narrative or prop. This cropping compresses the sitter into our space, as if we had turned in a doorway and found him already there. Caravaggio repeatedly used such tight framing to convert viewers from spectators into interlocutors. The “gentleman” becomes not a subject of biography but a partner in a silent exchange. The small scale intensifies that effect: at close distance the paint reads as skin and hair more convincingly than at exhibition remove.

Costume and Social Temperature

Although the costume is sketched rather than catalogued, it carries just enough information to register status. The sitter wears a buff-colored doublet with a sliver of patterned sleeve peeking from under a darker overtunic, and a white collar that opens at the throat. The garments are neither aristocratic finery nor peasant rags. They place the man in the world of artisans, soldiers, or minor officials—a social middle that Caravaggio knew well from the streets and the taverns of Rome and Naples. The absence of emblems or jewelry is deliberate; identity is anchored in the face, not in possessions. The clothes, like the background, recede into warm shadow once their basic function has been served.

The Face as Landscape of Experience

Caravaggio’s portraits are rarely flattering; they are sympathetic. The sitter’s forehead carries the memory of furrow; the nose is slightly broad; the mouth tight. What we notice, though, is not irregularity but life. The skin is modeled with small modulations that record age without cruelty. The eyes smolder rather than shine—two low coals set under a storm of hair. Their direction is not fixed; depending on the viewer’s position they seem to flick slightly to the side or directly outward, a parallax effect created by careful alignment of pupils and eyelids. This ambiguity fuels the portrait’s psychology. The man looks as if he has recently turned from something, perhaps conversation, perhaps trouble, and now measures us with a guarded curiosity.

Brushwork, Ground, and the Fact of Paint

Up close the surface reveals Caravaggio’s economy. He blocks large planes of shadow with thin, absorbent layers that let the ground tone breathe through. Over this he floats opaque passages to catch light, especially along nose, cheek, and collar. Hair is massed broadly, with only a few stray curls articulated; the beard is suggested with dark scumbles and a handful of bright strokes at the mustache edge. The white collar bears the most painterly flourish: a handful of loaded touches that describe linen with convincing crispness. This alternation—thin shadow, dense light—creates the portrait’s living texture while reminding us that we are looking at painted matter, not mimetic magic. The candor of the paint parallels the candor of the gaze.

Caravaggio’s Psychology Without Allegory

Unlike allegorical heads or “character types,” this portrait does not load the sitter with emblematic weight. No fruit, no musical instrument, no book offers a caption. The painter trusts that a human face, given honest light, contains its own meanings. The man is not “melancholy” or “music” or “war”; he is himself. In this, Caravaggio anticipates modern portraiture’s respect for subjectivity. He avoids the Renaissance impulse to refine features toward ideal and refuses the Mannerist one to twist character into emblem. The truth he prefers is immediate and specific: pores, stubble, the shadow of a day’s labor, the glint in a wary eye.

The Poise Between Vigilance and Weariness

A compelling tension animates the picture: the sitter appears both alert and tired. The heavy hair and mustache give weight to the head, while the eyes keep an edge. That poise is characteristic of Caravaggio’s people—creatures of the street who have seen too much and yet remain awake to the next moment. In religious scenes the artist uses such faces to ground miracles; in a secular portrait he lets the same physiognomy speak for itself. The result is an image that feels honest to human thresholds: the hour when the day is nearly done but one must still attend to what is happening.

The Role of Darkness as Character

In many portraits, background is a neutral stage. Here the darkness is an actor. It presses against the head, softens the silhouette, swallows detail while giving back a gentle vibration of reflected light. It is not a void; it has air. Caravaggio uses this environment to sculpt the figure without recourse to linear outline. Edges dissolve, especially along the hairline, so that the face seems carved by illumination rather than drawn. This, too, supports the painting’s psychological reading: the sitter is a person emerging from a life we cannot fully see, brought forward momentarily by our attention.

Possible Functions and Attributions

The painting’s scale and informality suggest it could have been a study from life, a gift to a patron who valued character over finery, or a fragment of a larger enterprise—a head prepared for a figure in a larger composition. Caravaggio often relied on real people for sacred dramas; such a portrait would have served as a store of lived physiognomy. The ambiguity of date and purpose adds to the object’s fascination. It sits at the threshold between private likeness and public type, between diary entry and finished work.

Light as an Ethical Choice

Caravaggio’s light is never merely optical; it is moral. To reveal a man’s face this frankly is to respect him. The painter does not flatter or humiliate. By illuminating forehead, cheek, and collar while leaving clothing and background obscure, he states a hierarchy: the person matters more than the polish. That ethic is consistent across his oeuvre—from apostles and martyrs to gamblers and musicians—and it is present here in distilled form. The portrait tells us as much about the artist’s stance toward the world as it does about the sitter: attention is a form of justice.

Comparisons with Other Heads by Caravaggio

Set beside early Roman portraits and later Neapolitan heads, the “Portrait of a Gentleman” shares a family of traits: compressed framing, a warm ground, and a whispered background tonality. Yet it feels more intimate than court commissions and less theatrical than narrative canvases. It lacks the bravura finish of a state portrait, choosing instead the slightly roughened surface of lived truth. In this way it aligns with Caravaggio’s studio habit of painting directly from life, sometimes rapidly, trusting light to resolve anatomy where drawing would be cumbersome.

The Collar and the Moment of Brightness

One detail deserves special notice: the white collar. Against the umber field it flares like a small flag. The linen’s crease catches a bright touch; the edge turns with a brisk line; a shadow slips under the fold to separate cloth from beard. This little form does several jobs. It acts as a reflector, bouncing light up into the jaw; it punctuates the composition with a decisive shape; and it signals the sitter’s care for appearance without lapsing into vanity. In a painting nearly monochrome, the collar’s coolness gives the eye a place to rest before returning to the heat of the face.

The Viewer’s Role in Completing the Portrait

Caravaggio leaves narrative gaps for the viewer to fill. Who is this man? Soldier, artisan, messenger? Friend, model, stranger? The painting offers no answers, only clues in demeanor and cloth. This openness is part of its magnetism. The image invites imaginative collaboration while restraining fantasy with the discipline of observation. We may project stories, but the face keeps us honest. It resists melodrama the way a real person does: by being specific.

Time, Texture, and the Beauty of Wear

The picture also honors time. The sitter’s features carry wear; the paint’s surface seems to accept patina, as though age were not an enemy but a collaborator. Caravaggio, who knew precarious living, often found beauty in the evidence of use—patched garments, grimy walls, scarred wood. Here that ethic yields a portrait where even the roughness along the panel’s edge and the uneven absorption of the ground contribute to the sense of authenticity. Perfection would have betrayed the man.

Why This Portrait Matters

“Portrait of a Gentleman” matters because it distills a vision of human dignity. In an era when portraits often proclaimed status through fabrics and insignia, this one elevates ordinary presence. It demonstrates how much can be said with a head, a collar, a warm darkness, and a few minutes of unflinching looking. It also reminds us why Caravaggio remains modern: he believes that truth resides in the encounter between light and a face, and that painting’s job is to hold that encounter long enough for thought to happen.

Conclusion

The unknown sitter, the unknown date, and the unknown occasion do not diminish the painting; they focus it. Caravaggio’s “Portrait of a Gentleman” is an essay in attention, a compact demonstration of how light, scale, and brushwork can convert anonymity into presence. The man emerges from darkness with a life that feels both private and shared. We do not know his name, but we recognize his alertness, his fatigue, and the guarded courtesy of his gaze. In that recognition, the portrait fulfills the highest task of the genre: it allows one human to be met by another across time, with neither flattery nor disdain, only the clarity of being seen.