Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

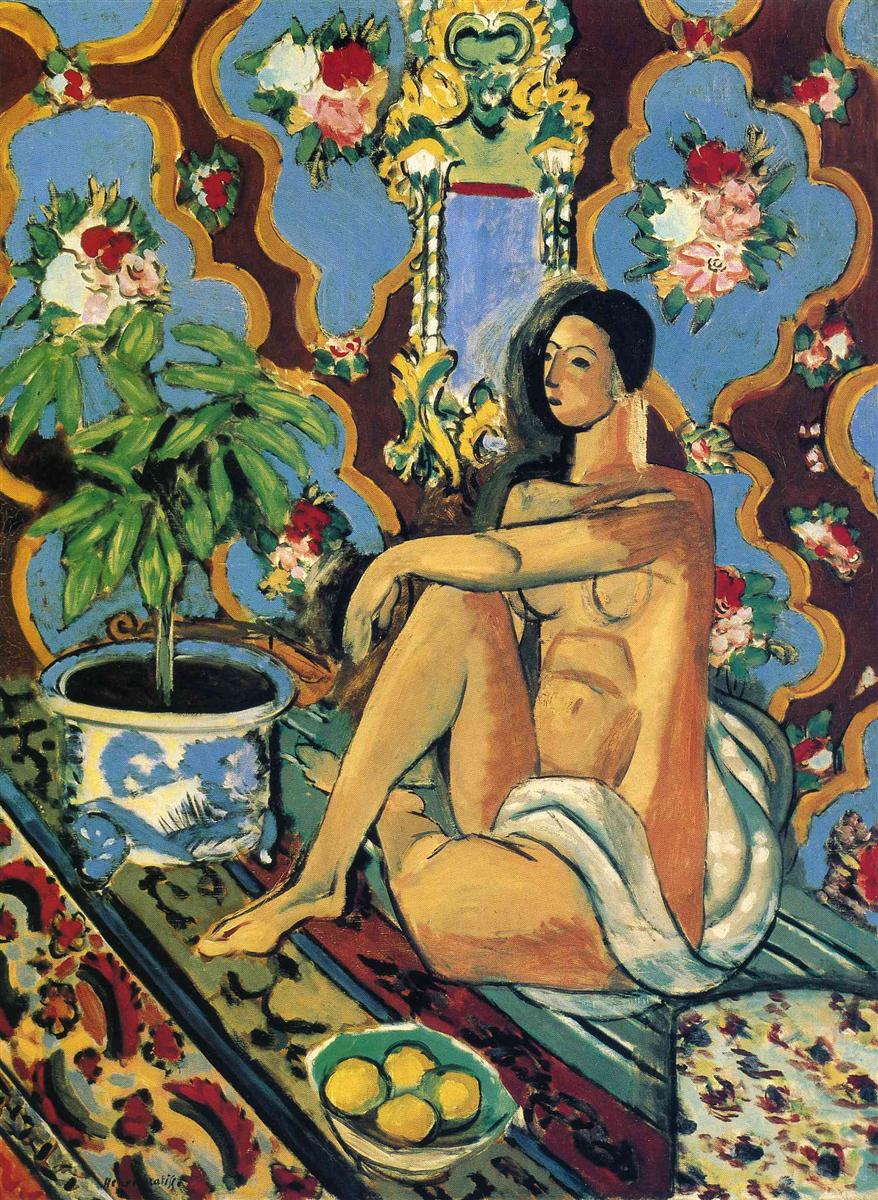

Henri Matisse’s “Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” (1925) is one of the most sumptuous statements from his Nice years, a period when interiors, textiles, and the female figure became instruments for composing pictorial harmony. The painting presents a seated nude wrapped in a pale drapery, poised on a carpet before a dazzling wall of blue cartouches, floral bouquets, and rococo flourishes. A potted plant anchors the left side; a mirror framed in gilded arabesques rises behind the model; a bowl of lemons glows near her feet. Although the scene teems with objects and patterns, nothing feels crowded. Matisse orchestrates the abundance so that color, rhythm, and silhouette settle into a poised equilibrium. The “decorative” in the title is not a dismissal; it is the central idea—the belief that ornament can be the very structure of modern painting.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Turn

By 1925 Matisse had spent several winters in Nice, refining a language of calm intensity that replaced the clashes of Fauvism with measured chords of color. The Riviera offered controllable light, a steady supply of studio props, and rooms that could be arranged like stage sets. “Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” exemplifies this trajectory: the boldness of early color remains, but it is tuned to a lyrical consonance; drawing is decisive yet relaxed; and space is treated as a shallow, breathable field where pattern and figure can meet as equals. The painting asserts that modernity need not depend on shock or fragmentation. It can proceed through clarity, balance, and the joy of relations.

Composition As A Theater Of Arabesques

The composition is designed like a proscenium. The figure, placed slightly to the right of center, forms a compact arabesque: a triangle of bent limbs and torso countered by the soft rectangle of the drapery. Behind her, the ornamental wall is organized into scalloped blue compartments edged with brown and sparingly gilded, each holding lush blossoms that echo the model’s curves. A gilded mirror, centrally positioned, supplies a vertical axis and a flare of light, while the carpet at the base introduces long diagonal runners that guide the eye forward. The potted plant on the left and the bowl of lemons on the right act as sentinels, balancing the figure’s mass and keeping the surface animated from edge to edge. Matisse’s stagecraft allows the eye to loop continuously—from plant to figure to mirror to carpet to lemons and back—without snagging on any single object.

Color As Architecture And Atmosphere

Color is the true architecture of the picture. The wall’s blues range from cerulean to powder, breathing coolness into the room and lifting the blossoms that erupt in coral, crimson, and milky rose. Brown tracery and touches of yellow-gold articulate the wall’s cartouches, preventing the cool field from dissolving into air. The model’s flesh is a warm chord of apricot, sand, and sienna, animated by lean washes and firmer notes along the ribcage, shoulder, and thigh. The drapery around her hips is a pale gray-blue that relays the wall’s coolness back into the figure, while the carpet underfoot introduces saturated reds and wines patterned with dark greens and blacks. The potted plant’s leaves deliver decisive greens that mediate between the red carpet and blue wall; the lemons repeat warm yellows in a higher key. The palette feels abundant, yet it is rigorously tuned: every hue is positioned to balance and amplify its neighbors.

Pattern As Structure Rather Than Ornament

The ornamental background is not a decorative afterthought; it provides the picture’s grid. The scalloped compartments of the wall act like musical measures, pacing the surface with gentle beats. Their floral bouquets are not naturalistic; they are painted bouquets of paint, clusters of strokes that behave as rhythm. The carpet’s stripes and whorls establish a counter-grammar of long lines and tight motifs, while the ceramic pot contributes blue-and-white arabesques that rhyme with the wall. These patterns flatten space just enough to emphasize the canvas as a plane, yet they never suffocate the figure. Instead, they create a responsive environment in which the model’s silhouette can register clearly against richly worked grounds.

The Figure’s Silhouette And The Authority Of Line

Matisse’s contour is both economical and expressive. The figure’s head tilts with a single sweep; the jaw and neck are given by firm, unbroken lines; the shoulder turns with a small thickening of paint; the knee reads with a confident arc that presses against the drapery’s soft fold. He models only where necessary, allowing color temperature and edge to carry the volume. Eyes, brows, and mouth are simplified into emphatic planes, giving the face a masklike introspection that resists anecdote. This clarity of line grants the figure a heraldic presence. Even when surrounded by pattern, she remains the axis of the image because her silhouette is so sure.

The Mirror, Reflection, And The Self-Awareness Of Painting

The ornate mirror behind the model is a pivotal device. Its reflective surface barely records a ghost of the room, reading mostly as a cool violet rectangle framed by gilded scrolls. Functionally, it injects a vertical blaze into the background and breaks the blue cartouche pattern. Symbolically, it is a picture within the picture, a reminder that the room we see is a constructed stage. Matisse does not chase literal reflections; he uses the mirror to fold the image back on itself, to declare that painting is an arrangement of colored surfaces that can acknowledge their own artifice without losing warmth.

The Plant, The Lemons, And The Poetics Of The Studio

The potted plant at left and the bowl of lemons at right expand the image’s vocabulary without complicating it. The plant’s leaves are built from loaded green strokes, each leaf a summary of light, volume, and vein. The pot’s blue-and-white painting echoes the wall’s motifs and affirms the studio as a place where decorative objects converse. The lemons, luminous in a shallow bowl, introduce hard geometric circles that answer the model’s knees, breasts, and the cartouche roundels. These familiar props keep the composition domestic and tangible, rooting its splendor in everyday materials.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Although the carpet tilts and the plant recedes, space remains gently compressed. The wall pushes forward; its pattern is a shallow tapestry more than a distant plane. The figure sits on the carpet yet reads against the wall almost like a cut-out, as if Matisse were rehearsing the late paper works he would produce decades later. This productive flatness gives the painting its modern charge. The eye toggles between reading a room with objects and reading a concert of shapes on a flat surface. That oscillation is not a flaw; it is the engine of the picture’s liveliness.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The painting’s title and props acknowledge a lineage of odalisques, screens, and patterned fabrics historically linked to Orientalism. Matisse had studied North African ornament and absorbed its lessons—the love of flat pattern, the primacy of arabesque, the dignity of decorative order. In this work, he redirects the tradition away from fantasy and toward formal inquiry. The figure is not a harem curiosity but a modern collaborator whose body is treated with the same structural respect as a carpet’s warp or a vase’s silhouette. Cultural signs remain, yet they function as components in a visual grammar rather than as ethnographic spectacle.

From Fauvism To Lyrical Classicism

“Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” carries forward the liberation of color achieved in the Fauve years while tempering it with classical judgment. The palette is vivid but not violent; complementary contrasts are moderated by the cooling presence of blue; and blacks are used not as void but as articulate drawing. Where the early Fauves pursued shock, the Nice period seeks steadiness. The painting demonstrates how Matisse’s radical colorism matured into an art of long phrasing, where intensity is sustained rather than shouted.

The Surface And The Evidence Of Making

The painting’s serenity contains the memory of work. Brushstrokes remain legible: quick dabs for blossoms, longer pulls for drapery, thick, slow strokes for the gilded mirror. In places you can sense adjustments—an edge drawn and softened, a motif repainted to square with a neighboring rhythm. These pentimenti are not distractions; they thicken the harmony with time. They remind the viewer that calm is constructed from many decisions, that ease is an outcome rather than a default.

Music, Rhythm, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse often compared painting to music, and this canvas makes the analogy precise. The wall’s cartouches establish a steady meter; bouquets are trills and turns; the carpet’s runners act as bass lines; the lemons are clear, bright notes; and the figure is the sustained melody that gathers them. The painting asks to be seen at the pace of adagio. As the eye moves, relationships emerge—a green leaf aligning with a green shadow on the drapery, a stroke of coral in a bouquet answering the warm note on the model’s shoulder, a triangle in the carpet echoing the bend of the knee. Looking becomes listening.

Psychology, Presence, And Modern Poise

The model’s expression is inward and composed. She is neither coy nor grand; she is present, self-possessed, and at ease in a room that seems to recognize her shape. The crossed limbs close the figure into itself without turning inward; the left arm’s line carries the gaze toward the face, where a small dark accent at the eye steadies the mood. The result is psychological quiet. In an age fascinated by speed and rupture, the image proposes a different modernity—poise, attention, and a belief that order can be sensuous.

Dialogue With The Decorative Arts

Matisse’s dialogue with textiles, tiles, and furniture is unusually explicit here. The wall behaves like painted ceramic or printed fabric, the carpet like a portable garden of motifs, the pot like a fragment of porcelain history. This conversation elevates the so-called minor arts to partners in painting. It also clarifies Matisse’s conviction that decoration is not superficial. Pattern is a way of thinking. It is a method for organizing experience into a field where differences hold together without erasing one another.

Anticipations Of The Cut-Outs

The firm silhouette of the model against the insistent wall points forward to the paper cut-outs of the 1940s and 1950s. In those later works, color and shape are literally cut and arranged; here, they are painted as if already cut, with contours that read like scissors’ paths. The ornamental background anticipates the later compositions where figure and ground interlock without hierarchy. “Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” thus functions as a hinge in Matisse’s career, proving that the decorative intelligence of Nice could evolve into the radical flatness of the cut-outs.

The Ethics Of Pleasure

Pleasure has an ethic in Matisse’s work. It is not a distraction from seriousness but a rigorous achievement. This painting demonstrates how pleasure is built: through calibrated contrasts, through the respectful spacing of elements, through the precise tuning of warm and cool, and through the clarity of edges. The room’s joy is not syrupy; it is lucid. Such lucidity carries a promise—the promise that everyday life, arranged with care, can become a chamber of well-being.

Why The Painting Endures

The painting endures because its pleasures are structural and inexhaustible. Each viewing discloses new alignments: a lemon mirroring a floral bud, a blue in the pot answering a shadow in the mirror, a brown line at the wall subtly reinforcing the figure’s calf. The image demonstrates an art that is generous and exacting at once. It welcomes luxuriant color, celebrates pattern, dignifies the human figure, and keeps the whole field in balance. It is a complete world on a single plane, a demonstration that the decorative can be profound.

Conclusion

“Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” is not merely a portrait of a model in a richly ornamented room. It is a manifesto for a way of painting and, by extension, a way of seeing. Matisse offers an interior where the forms of the decorative arts, the human body, and the rhythms of color coexist without hierarchy. The result is quietly radical. In place of narrative drama, he gives a sustained harmony; in place of descriptive depth, a thoughtful flatness; in place of exotic spectacle, a modern poise. The painting carries the viewer into a space where looking is rewarded by balance, and where the “decorative” becomes a serious, sustaining mode of thought.