Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

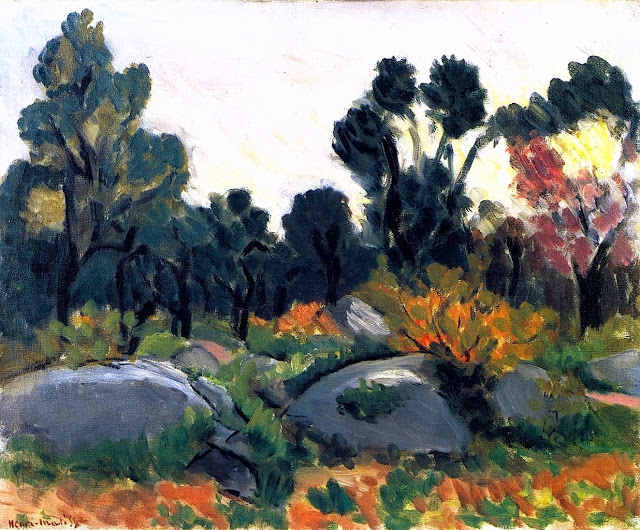

Henri Matisse’s “Rocks in the Vallée du Loup” (1925) is a rare excursion into pure landscape during the years when his Nice interiors dominated his practice. Painted in the hills above the French Riviera—near Villeneuve-Loubet, Grasse, and Vence—the Vallée du Loup offered a stony, scrubby terrain very different from the patterned rooms of his studio. In this canvas Matisse turns away from odalisques and musical still lifes to confront a slope scattered with granite boulders, low shrubs, and wind-shaped trees under a pale, almost vacant sky. The picture is not a topographical study; it is a meditation on how rock, vegetation, and light can be organized as chords of color and rhythm. The result feels at once outdoorsy and deeply composed, carrying forward lessons from Fauvism while speaking in the calm, clarified voice of the 1920s.

The Return to Landscape in the Nice Years

Throughout the Nice period, Matisse often painted interiors because they allowed him to control light, arrange pattern, and rehearse harmony. Landscape is riskier: the world insists on its own complexity. “Rocks in the Vallée du Loup” shows how he met that challenge by editing nature into a structure of interlocking masses. The composition preserves the sensation of being out in the sun yet remains unmistakably constructed. You feel the breeze in the treetops, the warmth reflecting from stone, and the irregular rhythm of scrub and boulder, but every element answers a pictorial need. Landscape becomes another kind of “room,” this time furnished by rocks and trees rather than chairs and curtains.

Composition as a Field of Masses and Intervals

The canvas is organized as a shallow amphitheater. Large stones occupy the foreground like seated figures, their broad gray planes establishing a base note. Shrubs and low, flame-colored bushes pour through the gaps, and a dark band of tree trunks forms a loose colonnade across the middle distance. Above them, the treetops push against a spacious sky. The diagonals of boulders guide the eye from left to right and back again, while the verticals of trunks anchor the sweep. This interplay between diagonal thrust and vertical check gives the picture its tempo. Nothing is centered; everything is slightly off-balance in a way that feels natural. The composition unfolds as a series of intervals—stone to shrub, shrub to tree, tree to sky—each transition measured to keep the surface alive.

The Palette: Earth and Air in Fauvist Afterglow

Color carries the sensation of the place. The rocks are laid in cool grays tinged with blue-violet and warmed with sunlit creams along their edges. The greens are varied: deep bottle greens in the tree band, olive and jade in the shrubs, and acid highlights where sun strikes young leaves. Rusts and oranges flame up in scrubby bushes that read like autumn or late summer burnished by heat. The sky is a high, milky white with traces of lemon and faint pink, more felt than described, allowing the darker masses below to stand forward. This orchestration recalls Fauvism—the autonomy of color from strict naturalism—but the chords are tempered. Instead of the incendiary clashes of 1905, the painting offers tuned relationships capable of sustaining long looking.

Drawing, Contour, and the Gesture of Trees

Matisse’s drawing remains decisive even in the open air. He uses elastic black-green contours to articulate tree trunks and to crown them with tufted, wind-stirred foliage. These calligraphic silhouettes are not botanical portraits; they are gestures that stand in for a species of motion. Around the rocks, edges alternately harden and soften so that forms turn without heavy modeling. The “drawing” is often done with shifts in temperature rather than with lines—cool gray against warm gray, green against orange. Everywhere, structure arises from the economy of marks. You sense the artist selecting, abbreviating, and placing, instead of copying the hill shrub for shrub.

Light, Shadow, and the Mediterranean Air

The light is southern but not theatrical. Instead of high-contrast drama, Matisse gives us a pervasive brilliance that whitens the sky and lifts color from within. Shadows under boulders are violets and cool blues, not black; the dark band of trees is aerated with small punctuation marks where light drips through leaves. This treatment registers the Riviera’s dry clarity, where objects cast firm but not crushing shadows and the atmosphere opens space rather than swallowing it. The painting reads as midday or late morning—the hour when color is full but edges are still soft with heat.

Space, Depth, and Productive Flatness

Despite the suggestion of a deep slope, the landscape is deliberately compressed. The boulder band stands like a shallow stage, and the trees press forward as a patterned screen. The sky, while expansive, is a flat plane against which the silhouettes perform. This productive flatness echoes Matisse’s interiors, where wallpaper and textiles push toward the surface. Here nature provides its own “patterns”: the repeated ovals of foliage, the broken seams of rock, the tessellation of leaf and light. Depth exists, but it serves the decorative order of the canvas.

The Rhythm of Brushwork

Close looking reveals a rhythm of touches. Trees are topped with quick, comma-like strokes that cluster into crowns; shrubs are scumbled with short, vigorous dabs that suggest dry leaves; rocks are spread with broader, trowel-like sweeps that expose the texture of the canvas. The foreground’s burnt-orange earth is laid with broken strokes that let the ground peek through, producing a vibrating warmth. This variety of touch gives each kind of thing its own physicality while keeping the whole surface unified as paint.

The Rocks as Sculptural Actors

The boulders are the painting’s protagonists. They anchor the scene and dictate the movement of the eye. Their masses are simplified into broad planes so that they read as both geological and geometric. Light licks along their top edges in quick, creamy highlights, and darker clefts carve out divisions between them. The rocks’ stoic gray counters the vivacity of surrounding greens and oranges; they are the slow voices in the composition’s choir, providing ballast and gravity. In their simplified monumentality you feel an echo of Cézanne’s provençal stones, filtered through Matisse’s looser, more decorative sensibility.

Vegetation as Flame, Fabric, and Counter-Mass

If rocks give ballast, shrubs and trees give movement. The low fire-colored bush at center behaves like a flare, igniting the cooler greens and pulling the gaze forward. The band of trees behind is almost textile-like, a frieze of dark arabesques against pale air. In many of Matisse’s interiors, pattern holds the room together; here, the repeated leaf masses perform that function, knitting boulders and sky into a continuous surface. The tension between these soft organic clusters and the hard rock planes strengthens both.

The Sky as Silence

The sky occupies nearly a third of the canvas and is treated as a high, pale silence. Matisse refuses to clutter it with descriptive cloud forms; instead he lays a lightly modulated field that gives the darker silhouettes their resonance. This choice keeps the painting from becoming congested and allows color to breathe. The white-leaning sky also echoes an important Nice-period principle: relief through lightness. Interiors gained relief from windows and shutters; this landscape gains it from a sky that behaves as an airy, reflective ceiling.

Memory, Motif, and Plein-Air Discipline

Whether painted entirely outdoors or finished in the studio, the canvas feels grounded in direct observation and completed by memory. Certain passages—quick branches, abbreviated shrubs—read like on-the-spot notation. Others—carefully placed color chords, the overall balance—suggest later editing. The mix aligns with Matisse’s broader method: encounter the motif, secure its essential rhythms, then compose. The Vallée du Loup becomes less a site than a motif, akin to a vase or chair, capable of being tuned until it sings.

Dialogue with Fauvism and Classical Calm

“Rocks in the Vallée du Loup” mediates between two Matissean modes: the wildness of Fauvism and the order of the Nice interiors. From the former it inherits liberated color and confident simplification; from the latter, balanced intervals and temperate light. The painting neither shouts nor whispers. It speaks in a clear mezzo voice, allowing the viewer to dwell in its chords. The rocks, trees, and bushes are not excuses for virtuosity; they are the means by which harmony is achieved.

Geography and the Sense of Place

The Vallée du Loup is a limestone gorge carved by the Loup River, its slopes dotted with olive, oak, and Mediterranean scrub. Matisse’s painting catches that geology and botany without literalism. The grayness of stone, the scrub’s stubborn greens, the spiky profiles of small trees, and the dryness of the earth all register. Yet the picture refuses scenic prettiness. It favors the stubbornness of matter and the vitality of growth. The landscape is not a backdrop for sentiment but a partner in compositional thought.

The Ethics of Attention in a Non-Human Subject

In the Nice interiors, human presence—models, musicians, odalisques—serves as the axis of order. In this landscape, attention itself becomes the subject. The rocks and trees do not look back; they ask for a slower kind of looking. Matisse answers by giving every register of the scene its due: dark and light, warm and cool, hard and soft. The painting models an ethics of regard for the non-human, where plants and stones command the same disciplined care he afforded to people and rooms.

Material Presence and Evidence of Process

Across the surface are traces of revision: a trunk repositioned with a darker stroke, a rock edge softened by a warm scumble, a shrub brightened with an added orange flare. These pentimenti do not disturb the harmony; they enrich it with time. The viewer senses the painter’s negotiations—when to break a silhouette, when to leave a passage open, when to settle a rock’s plane. The landscape’s calm is therefore honest, containing within it the record of choices that made calm possible.

Why the Painting Endures

“Rocks in the Vallée du Loup” endures because it condenses a complex philosophy into a spare scene. It demonstrates that harmony is not the enemy of energy, that simplification can carry sensation, and that painting outdoors need not surrender to anecdote. The viewer returns for the balanced tension between boulder and bush, for the way the pale sky lets color sound, for the brushwork that feels both urgent and measured. The canvas offers an alternative to spectacle: sustained attention transformed into durable pleasure.

Conclusion

In this landscape Matisse shows that the Nice period’s decorative intelligence is not confined to interiors. The Vallée du Loup becomes a studio without walls—a place where rocks act as architecture, shrubs as pattern, and trees as calligraphy. Color is tuned rather than shouted; drawing is assertive but generous; atmosphere is clear without chill. The painting gives us a hillside at midday and, more importantly, a way of seeing it: as a concert of forms that hold one another in balance. It is a modest masterpiece of relation, proof that a few stones, a clutch of trees, and a large, breathing sky can contain a world.