Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

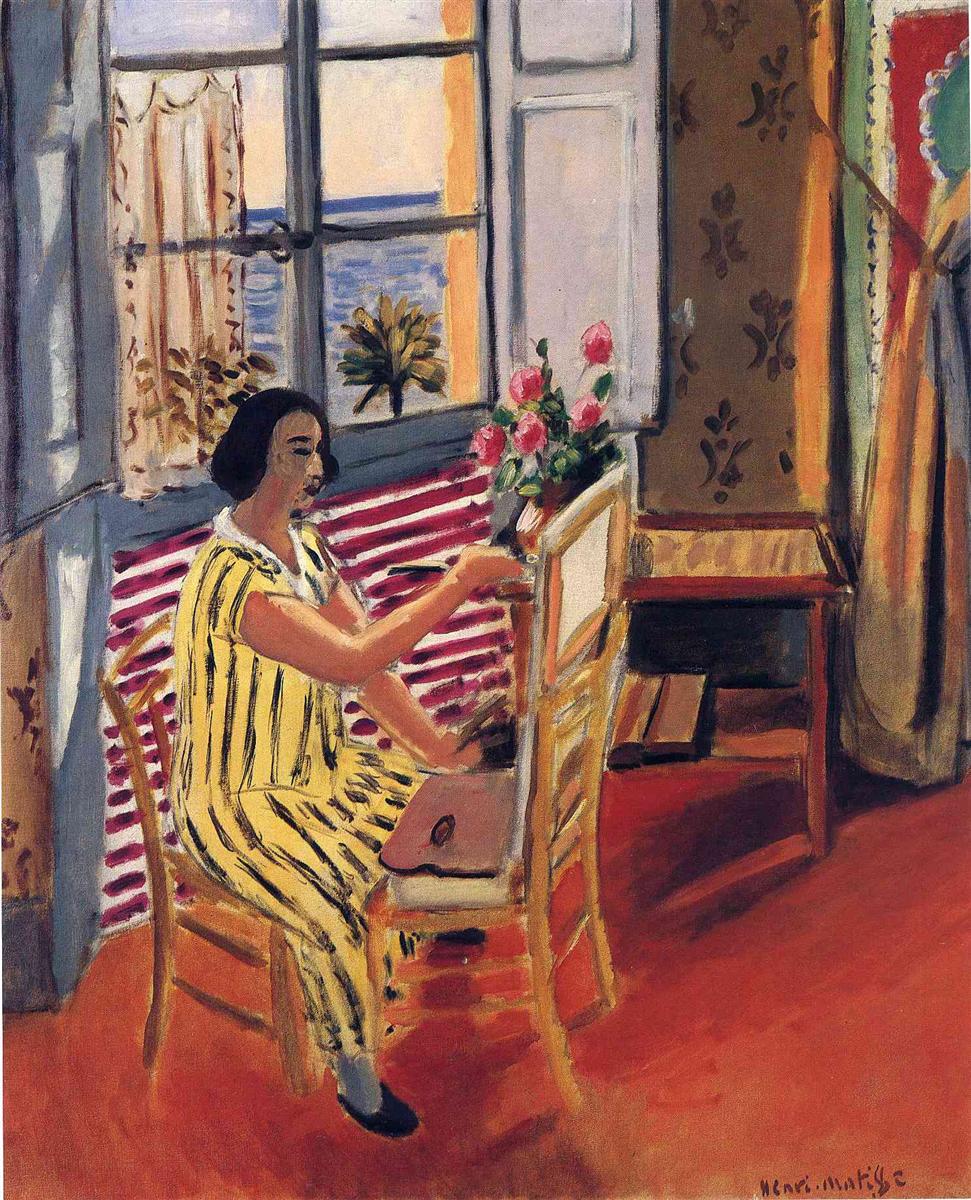

Henri Matisse’s “The Morning Session” (1924) belongs to the luminous series of Nice interiors that defined his art in the 1920s. Painted after his move to the French Riviera, it captures an everyday scene at once intimate and theatrical: a woman seated at an easel in a sun-washed room, with the Mediterranean visible through tall windows. The composition is modest, yet the orchestration of color, line, and pattern turns an ordinary morning into a celebration of sensation. In this period Matisse refined the radical colorism of Fauvism into a poised decorative language, seeking a painting that would be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind.” The canvas offers precisely that—an image in which domestic life, artistic labor, and Mediterranean light come into equilibrium.

Historical Context and the Nice Period

By 1924 Matisse had been working in Nice for several years, finding in its climate and architecture a laboratory for painting interiors infused with outdoor light. The Nice period is characterized by open windows, patterned textiles, flowers, screens, and models posed in rooms that feel more like stages than private spaces. This move did not represent a retreat from modernism; rather, it allowed Matisse to pursue modernity through harmony, simplification, and the decorative unity of the surface. “The Morning Session” exemplifies this shift: intense hues remain, but they are moderated and carefully tuned, the brushwork supple rather than brash, the arabesque line more musical than urgent. The subject—a model or artist at work—also mirrors Matisse’s own daily discipline and signals a meta-reflection on painting itself.

Subject, Setting, and Everyday Ritual

The painting’s narrative is unpretentious. A seated woman in a yellow, vertically striped dress faces a small easel. On the table sits a vase of pink blossoms, a fresh counterpart to the model’s rosy complexion. The wide windows behind her open onto a sliver of sea and a palm, a reminder that the room is not a sealed interior but a conduit for the outside world. The striped curtain, the patterned wallpaper, and the terracotta floor generate a cadence of repeating motifs. Morning, here, is not just a time of day but a ritualized condition: calm, order, readiness. The pose suggests that the session has only recently begun; the stillness is charged with expectancy.

Composition as Choreography

Matisse composes the scene like a choreographer arranging movements across a stage. The figure sits slightly left of center, counterbalanced by the pale mass of the window and the deeper ochres of the right wall. Diagonals guide the eye: the angle of the sitter’s arm leads to the easel; the line of the chair legs echoes the tilt of the table; the sash of the open window nudges sightlines outward to the sea. These vectors stabilize the picture while also preventing stasis. The spatial arrangement is intentionally simple, almost schematic, so that compositional energy arises primarily from relationships of color, contour, and pattern rather than from literal depth.

The Orchestration of Color

Color does the heavy lifting. The floor is a saturated reddish orange—warm, enveloping, and energetic—against which the cooler slate blues of the window and shutters vibrate. The yellow dress, shot through with black stripes, acts as a mediator between these poles. It picks up warmth from the floor yet remains luminous against the blue surrounds. Pink roses provide a chromatic echo of the floor while introducing a higher-key note that keeps the palette buoyant. Matisse has long abandoned local color as mere description; instead, he uses color to construct sensation and mood. The reds, yellows, and blues are tuned to produce balance without dullness, a careful “temperature” control that feels like late morning sunlight filtering into a quiet room.

Pattern as Structure and Melody

The Nice interiors are famous for their proliferation of patterns, and “The Morning Session” is a masterclass in how pattern can structure a painting without overwhelming it. The vertical stripes of the dress establish a rhythm that contrasts with the horizontal bands of the curtain. The wallpaper’s small repeating motif plays a softer accompaniment, while the chair’s caned geometry and the easel’s slender uprights add a finer counterpoint. These patterns operate like musical voices in a chamber ensemble: distinct lines that contribute to a larger harmony. They flatten space just enough to emphasize the canvas surface, reminding the viewer that this is an arrangement of shapes and colors, not a window to a measurable room.

Line, Contour, and the Calligraphic Touch

Matisse’s drawing is decisive and calligraphic. The figure is outlined with fluid, unbroken contours that feel closer to ink drawing than to modeled oil paint. Black lines enliven the yellow dress, tying drawing directly to color. The chair, easel, and window are rendered with economical strokes that imply volume without heavy shading. This blend of economy and decisiveness creates an elegant shorthand, allowing form to remain legible even as it is simplified. The line does not imprison color; it animates it, like a musical notation that invites performance rather than prescribing it.

Light, Atmosphere, and the Mediterranean

Light in this painting is not a strictly optical phenomenon but an affective one. The open window admits the Mediterranean in the form of a soft, pale sky, a band of sea, and the silhouette of a palm. This cool vista reframes the warm room as a sheltered interior bathed in refracted daylight. The light is diffuse, not dramatic; there are few cast shadows, and objects are defined more by color edges than by tonal modeling. This treatment creates a sense of calm clarity—an atmosphere in which details can be simplified without losing presence. The result is a painting that feels simultaneously anchored and airy, domestic and coastal.

Space, Depth, and Productive Ambiguity

Matisse engages spatial depth with a gentle ambivalence. The floor recedes, but not according to strict linear perspective. The table’s top tilts, the chair’s legs are slightly elastic, and the easel is simplified into planar bars. These controlled deviations are not errors; they are choices that privilege the painting’s surface logic over measured geometry. The interior reads as inhabitable, yet every object answers first to the composition’s decorative order. This ambiguity keeps the eye alert and prevents the comfortable subject matter from becoming merely anecdotal.

Gesture, Process, and Material Presence

The paint handling is frank. Areas of the floor and wall appear thinly brushed, allowing the ground to breathe through. Other passages, like the roses and the woman’s hair, are denser and more tactile. The alternation of thin and thick applications produces a quiet rhythm that echoes the alternation of patterns. Even when he paints quickly, Matisse never lapses into carelessness; the work feels edited, pared down to what is necessary for the image to sing. The signature in the lower right confirms the painter’s presence without drawing attention from the scene’s equilibrium.

The Figure as Axis of Harmony

The seated woman is not individualized in a psychological sense; she functions as the painting’s axis of harmony. Her yellow striped dress is a key chromatic element; her posture, slightly forward and attentive, aligns the room’s energies toward the easel. The face is simplified but tender, with a concentrated gaze that dignifies the routine of work. In Matisse’s interiors the model is often a collaborator in the orchestration of forms. Here, the woman’s containment—hands steady, feet grounded—anchors the proliferating patterns around her. She is the calm center that makes the decorative world coherent.

Flowers, Curtains, and the Poetics of the Everyday

The vase of pink flowers and the striped curtain are not mere studio props. They enact Matisse’s belief that beauty resides in ordinary things when arranged with feeling. The flowers echo the human presence, fragile and erect, while their circular heads rhyme with the curves of the chair backs and the ovals suggested in the wallpaper motifs. The curtain, meanwhile, is both a literal filter of light and a pictorial device for injecting rhythm into the background. These details carry no heavy symbolism; their “meaning” lies in their contribution to the overall accord, in how they help the viewer inhabit the serenity of the moment.

Continuities and Departures from Fauvism

Viewers who know Matisse primarily as a Fauve might be surprised by the painting’s poise. Yet the continuity is clear. The liberation of color from naturalism persists, as does the primacy of flat shapes outlined in confident black. What changes is the temperament. The discordant juxtapositions of the early years give way to a mature consonance, without surrendering intensity. The Nice interiors, including “The Morning Session,” refine the revolutionary impulses of the first decade into a sustained, lyrical idiom that would culminate in his late cut-outs. The same sensibility that would one day create floating shapes of paper is already present here in the insistence on surface, silhouette, and musical spacing.

Dialogues with Tradition

Matisse often acknowledged his debt to tradition, and this canvas subtly converses with earlier painters of interiors and women at work: Vermeer’s domestic poise, Chardin’s quiet concentration, Renoir’s luminous color. Yet Matisse diverges decisively by flattening space and foregrounding pattern. The window with a sea view recalls countless nineteenth-century seaside rooms, but its treatment as cool geometric panes framed by shutters belongs to the twentieth century. The easel on which the woman works reintroduces painting into the picture, echoing a lineage of meta-pictures from Velázquez to Courbet, while remaining humble and intimate rather than grand.

Rhythm, Music, and the Time of Morning

Matisse frequently analogized painting to music, and “The Morning Session” reads like a morning prelude. The stripes of the dress provide a steady vertical meter; the curtain’s bands add a horizontal counter-rhythm; small motifs—the flowers, the window panes, the chair rungs—punctuate the field like notes. Even the restricted value range contributes to a legato flow. The painting breathes in long phrases rather than staccato bursts. Morning, in this sense, is not simply bright; it is measured, practiced, ready to unfold. The canvas suggests a day beginning with discipline and grace.

Intimacy, Modernity, and the Role of Women

The subject resonates with ideas of modern domesticity. The woman is engaged in work—possibly painting, possibly arranging materials for the session—within a space that is both homelike and professional. Matisse’s interiors often dissolve distinctions between salon, studio, and stage, mirroring broader shifts in modern life where boundaries between private and public, leisure and labor, were being renegotiated. The sitter’s modern bob haircut and streamlined dress align her with contemporary fashion, while her stillness counters the restless pace of the outside world. Matisse grants the interior—and the woman within it—the dignity of modern life lived attentively.

The Window as Threshold

One of the painting’s key motifs is the window, a staple of Matisse’s Nice pictures. It functions less as an opening to deep space than as a framed color-field that balances the warm interior. The pale sky and slate panes are organized into rectangles that behave like painted panels; the view of sea and palm is compressed, almost emblematic. The window thus becomes a threshold between realms: the sensory abundance of the room and the vastness beyond. It also suggests that painting itself is a window of a different kind, filtering the world into harmonized shapes and hues.

Psychological Tone and Viewer Experience

Despite its stillness, the canvas is not aloof. The viewer’s eye can trace a path from the red floor up the chair and the sitter’s arm to the easel, then drift to the flowers and out the window, circling back along the curtain’s stripes. This looping itinerary replicates the calm attentiveness of a morning routine. There is no drama to resolve, only a sustained state to share. The painting invites inhabitation rather than interpretation. Its psychological tone is one of collected warmth, the kind of clarity that comes when a room is quiet and the day has just begun.

Influence and Legacy

Works like “The Morning Session” shaped the twentieth-century understanding of decoration not as superficial ornament but as a rigorous pictorial principle. The painting’s emphasis on pattern, flatness, and compositional melody fed into later developments in design, interior aesthetics, and abstraction. It anticipates Matisse’s cut-out period in its reliance on silhouette and color planes, and it has been a touchstone for artists who seek emotional richness through pared-down means. The legacy is not flashy; it is durable. The canvas stands as evidence that a carefully tuned room, a quiet figure, and a handful of colors can form a complete world.

Why the Painting Endures

“The Morning Session” endures because it condenses a philosophy of art into a familiar scene. It demonstrates that harmony is not a retreat from modern life but a way of meeting it with composure. The painting is generous in the pleasures it offers—color that glows without shrieking, lines that move without fuss, patterns that hum without crowding. In a century fascinated by speed and rupture, Matisse slowed time and made space for attention. The result is a work that feels perpetually fresh, like morning itself.