Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

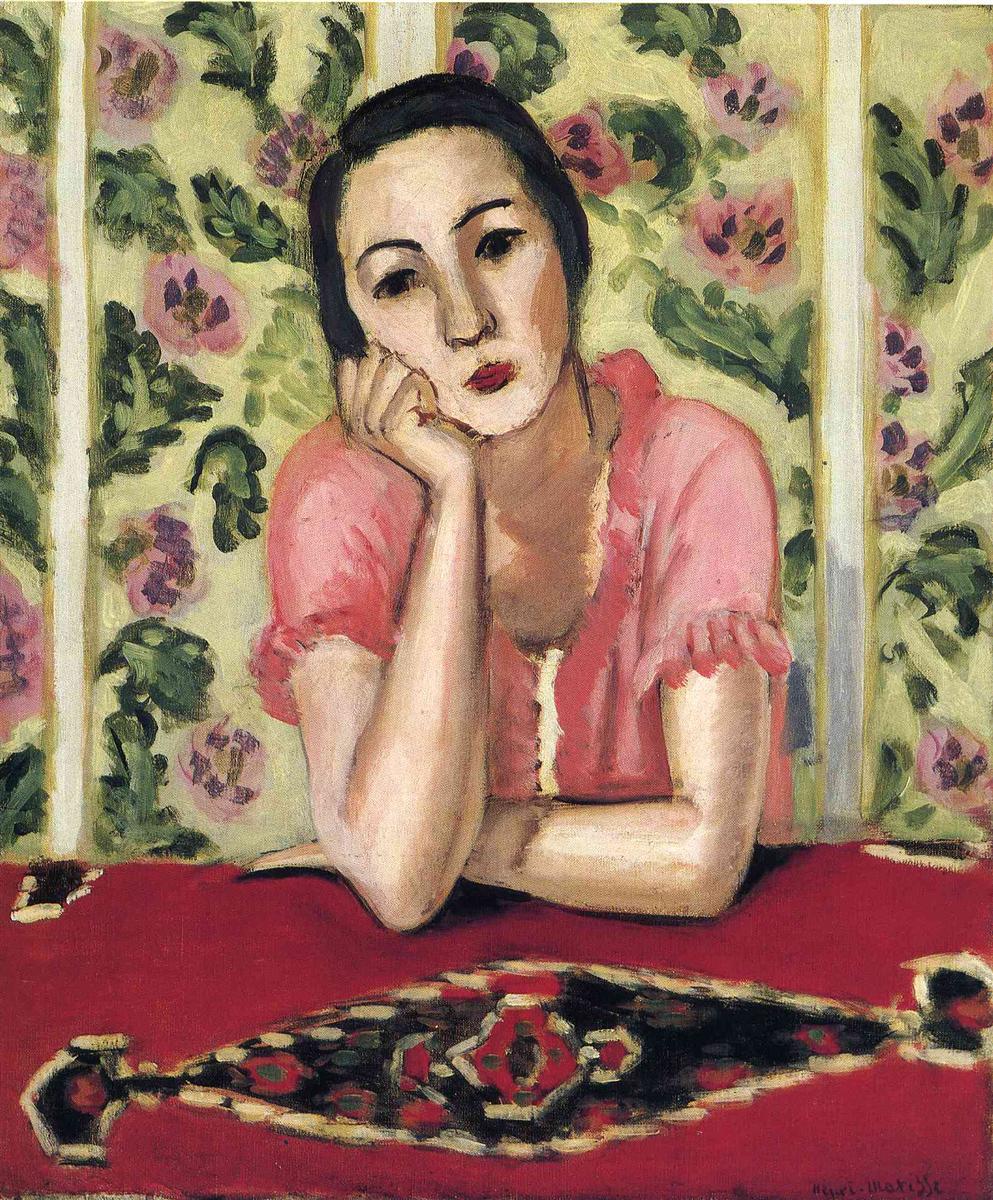

Henri Matisse’s “Pink Blouse” (1924) is a poised meditation on looking, pattern, and poise. A woman rests her chin in her hand at a red tabletop, arms crossed with relaxed assurance. Behind her rises a screen or wall of pale panels blooming with green leaves and rose-pink flowers. Her dress—an airy, frilled blouse in shades of coral and strawberry—echoes those blossoms while the dark, medallion-shaped motif on the table anchors the composition with a low register. The painting appears simple, but its orchestration is exact. Matisse transforms a small domestic moment into a complete visual chord where color and pattern carry feeling more persuasively than narrative.

Historical Context and the Nice Period Portrait

“Pink Blouse” belongs to the sequence of interiors that Matisse developed after settling in Nice in 1917. During these years he tempered Fauvism’s shock into a modern classicism built from ambient Mediterranean light, shallow layered space, and what he called a democracy of surfaces. In portraits from this period, figures cease to dominate through psychological drama; instead, they share the stage with textiles, screens, flowers, carpets, and furniture. The result is not detachment but clarity—an environment tuned to let color convey mood and rhythm. “Pink Blouse” exemplifies that approach: the sitter is present and dignified, yet she is also one element within a carefully balanced interior symphony.

Composition: A Triangle of Head, Arms, and Medallion

Matisse composes the figure as a stable triangle. The apex is the head, slightly tilted, resting in the right hand. The base is formed by the crossed forearms that lay along the tabletop. This triangle sits upon another, the dark diamond-and-ellipse medallion woven into the red cloth, which repeats and stabilizes the pose at a lower octave. Vertical floral panels behind the sitter create a slow cadence that counters the horizontal thrust of the table. The whole picture is paced by parallel systems: figure to tabletop, blouse to blossoms, face to medallion. Each part mirrors another at a different scale, giving the painting the satisfying logic of a musical variation.

Pattern as Architecture

Pattern is the true architecture of the scene. The floral backdrop is not merely decorative; it provides the shallow wall that asserts the painting’s modern flatness. Its leafy swirls and circular blooms echo the roundness of cheeks and elbows, harmonizing human and vegetal rhythms. The tabletop motif—dark, centered, and edged with a pale cord—acts like a plinth for the arms and chin, pulling the foreground into clear focus and preventing the eye from sliding out of the picture plane. Even the blouse’s frilled edges participate in this structural role: those scallops are a miniaturized border that sets the figure off from the background without isolating her from it.

Color Climate: Warm Pinks, Grounded Reds, and Leafy Greens

The color climate is a warm-cool dialogue, dominated by pinks and greens. The blouse’s coral tones sit between the saturated carmine of the table and the paler rose blooms behind. These hues are not sugary; they are tempered by warm earths and quiet grays in the skin, by a mossy green that keeps the floral field breathing, and by the rugged darks inside the table medallion and the sitter’s hair. The interplay is exquisite: pink speaks to pink across the room, while green answers as a complementary cool, creating a livable atmosphere rather than an illustration of color theory. Matisse deliberately withholds dead black; even the deepest accents contain color, so relations remain supple and humane.

Light Without Theatrics

Nice-period illumination is ambient and benevolent, and this painting breathes it thoroughly. Light arrives as a general wash—perhaps from a window out of frame—settling evenly across blouse, skin, and tablecloth. Highlights are milky and slow, like the softened gleam along the cheekbone or the quiet lift at the bridge of the nose. Shadows are colored rather than gray: a muted olive under the jaw, a warm tone at the crook of the arm, a soft maroon in the folds of the blouse. Because the light is even, color and drawing can carry the emotional temperature. The sitter appears absorbed, not staged; present, not dramatized.

Drawing and the Economy of Means

Matisse’s line is laconic and exact. The contour of the face is pulled in a single elastic sweep that thickens near the chin where the brush slows, then thins along the temple where it quickens. The hand supporting the cheek is described with the fewest possible turns; fingers are simplified into gently faceted planes that read as pressure and bone rather than demonstration. The blouse is built from broad planes whose edges bloom or tighten according to the brush’s pressure, while the frills are indicated by a few brisk scallops. Everywhere the drawing stops the moment structure stands, leaving color to do the rest. This economy keeps the surface fresh and aligns with the painting’s ethic of restraint.

The Sitter’s Presence: Calm, Concentrated, Unsentimental

The sitter’s expression is a quiet paradox: she seems both inward and available. Matisse avoids the habitual smile or the heavy frown; the eyes are dark and gently weighted; the mouth is a single soft accent of rose. Resting her chin in her hand, she reads as a person who is thinking rather than posing. The crossed forearms—a protective, comfortable posture—grant stability and intimacy. This is characteristic of Matisse: he refuses to narrate psychology yet achieves presence through equilibrium. The person feels real because the relations around her are precise.

Space by Layers, Not Vanishing Points

Depth is a sequence of short layers. Foreground: the red textile with its central medallion. Middle ground: forearms and blouse. Rear: floral panels pressed up toward the surface. The intervals between these layers are small, keeping the viewer close to the table edge and preventing any deep tunnel into space. Overlap—forearm over cloth, chin nested in hand, figure before screen—secures order without the anxiety of perspective lines. That shallow construction is central to the painting’s calm; it anchors the figure in the world of the surface while letting air circulate.

Rhythm and the Music of Looking

“Pink Blouse” is engineered like a piece of chamber music. Long notes include the broad red field of the table and the repeating vertical stiles between floral panels. Middle beats are the arms and torso, paced by the blouse’s frill and neckline. Quick notes spark as the glints in the eyes, the small notch of the nostril, the bright accents inside the medallion, and the tiny pale stitches of lace. The eye’s route is phrased: begin at the lower medallion, climb to the elbows, rest on the cheek cradled in the hand, drift into the floral blooms, and descend along the opposite arm back to the tabletop. Each circuit clarifies how pose, pattern, and color echo each other at different scales.

Touch and Material Presence

Beyond line and color, touch matters. The red cloth is laid with a slightly heavier, oil-rich stroke that leaves a gentle shine, implying a woven surface. The flowers behind are made of brisk, semi-dry passes that allow the ground to breathe through, giving the backdrop a powdery softness. Flesh is handled with supple, opaque paint that absorbs light; along the wrist and cheek Matisse scumbles thin color over thicker passages, creating the sensation of living translucency. The blouse alternates between transparent and opaque strokes, suggesting changing thicknesses of cotton and the glimmer of lace. These variations of pressure and paint weight keep the picture tactile, not merely decorative.

The Human Scale of Ornament

One of Matisse’s lasting lessons is that ornament can be human-scaled. The floral field does not overwhelm the sitter; it rhymes with her features and clothing. The table medallion does not distract; it supplies a bass line that steadies the composition. Ornament here is a way of pacing attention, not a way of showing off craft. By giving pattern the work of architecture, Matisse removes the need for deep shadows or theatrical light, allowing the person and her surroundings to share a single, breathable atmosphere.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Pink Blouse” converses with several neighboring works from the same years. Its floral panels and red tabletop echo interiors with vases and books, where the open window or patterned wall set the tonal key. Its crossed-arms pose recalls seated portraits he made in Nice, where hands, face, and textiles collaborate rather than compete. It also relates to the odalisque pictures without borrowing their theatricality: the blouse’s pink notes and the floral backdrop share that world’s decorative pleasure, but here the subject is simply a woman at a table, not an Orientalist fantasy. The painting distills the Nice-period creed: beauty achieved not by spectacle, but by measured relations.

Meaning Through Design

What does the painting propose? That calm is designed. A red cloth is chosen to ground the foreground; a blouse in sympathetic pinks is set against a floral field that repeats and diffuses those tones; a figure’s restful pose is balanced by a firm decorative geometry. The result is not sentiment but hospitality to attention. The sitter’s face becomes readable because the world around it is tuned. Matisse’s ethic is neither austere minimalism nor ornate display; it is equilibrium. He composes the kind of room—and the kind of gaze—where concentration feels like pleasure.

How to Look, Slowly

Enter through the dark center of the table medallion and let its pale edge lift you to the nearer elbow. Follow the sleeve frill up to the wrist and into the hand that cups the cheek. Pause on the cheek’s soft plane and count the small articulations around the mouth and eyes as if they were quiet beats. Drift into the floral field, letting a few blooms echo the blouse’s color, then return down the far arm to the edge of the table and across the red to the medallion again. Repeating the loop, you will feel the picture deepen without deepening space—the relations grow surer, and the presence of the sitter becomes more evident.

The Poise of the Face

Look closely at the face: it is drawn with the tolerance of a few millimeters. A cool gray articulates the eye sockets and gives the gaze its weight. A darker, elastic line secures the eyebrows and the outer edges of the nose. A small accent of rose-red finds the lower lip and ties the mouth to the blouse and flowers. The shadow under the chin is warm but restrained, maintaining the bridge between face and hand. Nothing is overmodeled; everything is stated exactly once. The effect is dignity without heaviness.

The Blouse as Agent of Harmony

The titular blouse deserves its own attention. Its pink is not single; it is a field of correlated notes—coral at the shoulder, strawberry along the sleeve, salmon and peach in half-tones where the fabric turns. Scalloped cuffs and a pale lace placket animate the edge zones without fragmenting the mass. In this garment Matisse invents a bridge between person and room: it borrows color from the floral wall and passes it to the table while remaining an independent presence. The blouse is not merely clothing; it is the picture’s mediator.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

Though nearly a century old, “Pink Blouse” feels modern because it refuses both theatrical psychology and icy design. It shows a person in a room where attention can rest. The face is simplified but not generic; the pattern is vivid but not loud; the color is saturated but breathable. This blend—a designed calm that never freezes—remains rare and difficult. It is why the painting still reads as fresh, and why it continues to teach how to look.

Conclusion

“Pink Blouse” is a compact statement of Matisse’s Nice-period mastery. With a tabletop, a floral wall, and a sitter in a coral dress, he composes a stable harmony where pattern serves as architecture, color carries mood, and ambient light joins all parts. The figure’s presence arises not from psychological spectacle but from the exactness of relations—chin to hand, blouse to blossoms, face to medallion, warm to cool. In that equilibrium the painting offers a usable wisdom: arrange the world with sympathy between parts, and everyday life becomes hospitable to attention.