Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

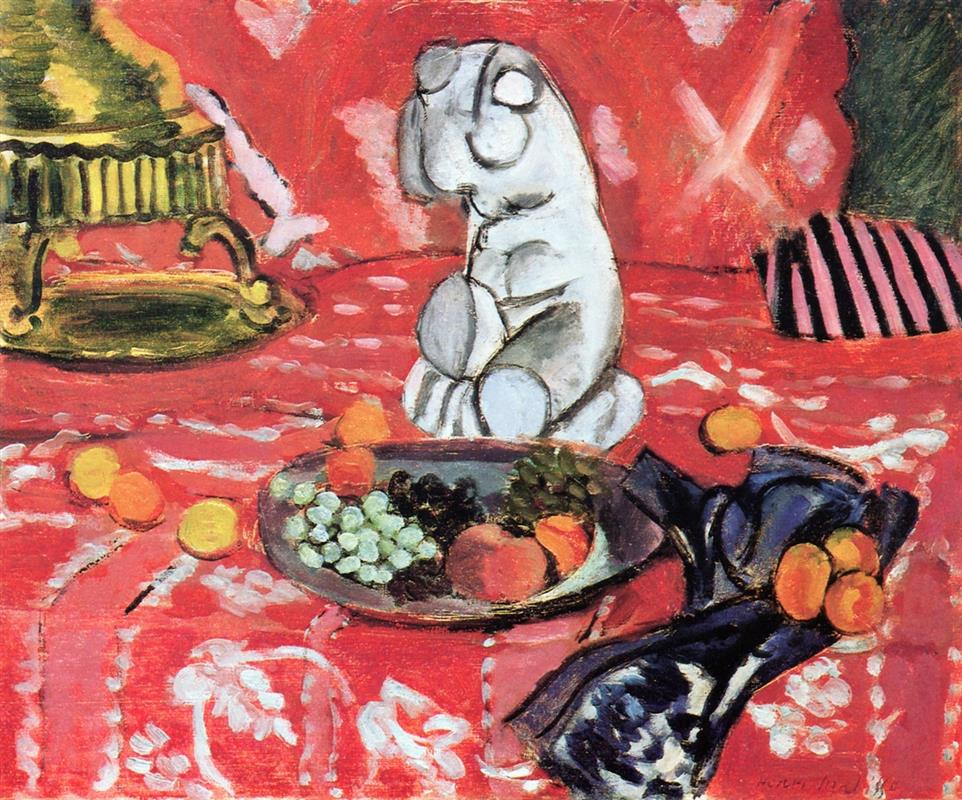

Henri Matisse’s “Still Life with Plaster Torso” (1924) is a radiant declaration of the painter’s Nice-period creed: transform the ordinary into a lucid harmony through color, pattern, and a few decisive lines. The scene is simple yet theatrically arranged. On a red patterned cloth, a small white plaster torso rises like a votive figure; to its side a shallow compote of grapes, peaches, and dark berries glows; at the left, the foot of a gilded stand intrudes; at the right, a folded indigo fabric spills a clutch of apricots. The tabletop becomes a stage where cool and warm hues, matte plaster and juicy fruit, ornament and contour all keep time together. Rather than serving as props for anecdote, these things are tuned like instruments in a chamber ensemble. The result is both sensuous and disciplined, abundant and calm—an exemplary statement of Matisse’s modern classicism.

Historical Context

By 1924, Matisse had refined the luminous language he developed after moving to Nice in 1917: shallow layered space, ambient Mediterranean light, and a “democracy of surfaces” in which figure, furniture, textiles, and objects share equal dignity. Still life was a laboratory for this language. In Nice, Matisse repeatedly staged fruit, flowers, and ceramics on patterned cloths against screens or wallpapers, exploring not just depiction but relation—how one color steadies another, how a curve echoes across the picture, how a pattern can function as architecture. “Still Life with Plaster Torso” is among the clearest of these exercises because its central object is art itself: a plaster cast, the artist’s studio companion, a cool white form that turns the surrounding red world into a halo.

Composition: A Stage Built from Ovals and Arcs

The composition is organized around a set of rounded forms that rhyme across the surface. The torso—headless and armless—stands at center, its compact ovals of breast, belly, and thigh stacked into a vertical totem. Beneath it, the red cloth is drawn up in soft swells; to the torso’s right, a folded indigo textile forms a diagonal wedge; to the left, a gilded stand repeats the theme with scalloped feet and an arched apron. Across the lower middle, a shallow oval dish tilts toward us, bringing the fruit into clear view. Scattered lemons and apricots extend the ellipse outward, and white arabesques in the cloth echo the torso’s curves in a larger key.

Matisse tilts the tabletop slightly so the objects sit securely in the picture plane, a favored Nice-period device that avoids deep perspective and keeps our attention on relations within the surface. The composition reads from left to right as a series of beats—golden stand, white statue, slate-gray dish, indigo fold—punctuated by small orange notes. The eye loops around the torso, then outward across the dish and fabric, finally returning to the bright fruits that orbit the figure like satellites.

The Plaster Torso: Cool Anchor in a Warm Sea

Choosing a plaster cast as the protagonist is not coy; it is strategic. The matte whiteness of plaster is a natural reflector that gathers the room’s colors while remaining structurally clear. Matisse models the torso with large planes—cool grays, lilac shadows, and sparing lines—so it reads as volume without heavy detail. The cast’s neutrality becomes a screen on which surrounding reds and greens can vibrate. It is also a conceptual center: an object made for looking in a painting about looking. The classical echo of the torso nods toward tradition, but Matisse drains it of narrative; it is neither allegory nor muse, only a serene form entrusted with stabilizing the riot of color around it.

Color Climate: A Chord of Red, White, Gold, and Indigo

Color organizes the painting’s atmosphere and its structure. The dominant field is a saturated, coral-red cloth whose intensity is softened by milky veils and chalky pink scumbles. Across this warm sea, the white torso rises as a cool island. Golds and acid greens in the stand at left introduce a metallic glint that keeps the red from becoming flat. The right side is cooled by a deep, inky blue fabric that spills into the foreground; its darkness sets the oranges aflame and returns the eye to the red ground. In the dish, grapes and berries provide a scale of greens from mint to bottle-dark; peaches and apricots reassert the warm chord.

Matisse avoids dead black, allowing even the darkest accents—berries, cloth creases, cast shadows—to carry chromatic life. Small touches of violet appear at contour and in half-shadows, knitting warm and cool. The palette is simple, but it breathes; each hue has a role to play in the equilibrium of the room.

Pattern as Architecture

The red cloth is far more than background. Its white arabesques and dotted reserves construct the space and control tempo. The looping floral tracery at the bottom edge establishes a steady decorative beat, while larger, cloudlike reserves in the upper field expand into slower pulses. These patterns do the architectural work that linear perspective might do in another kind of painting: they bind objects to the surface, prevent recession from becoming theatrical, and provide visual “air” where the eye can rest between saturated notes. Even the stripes of the tucked black-and-pink form at the right margin—perhaps part of a cushion—join the rhythmic fabric, adding a brisk counter-meter to the broad red phrase.

The Fruit and the Dish: Counter-Forms and Counter-Tempos

The oval dish is drawn with a confident, elastic line whose thickness changes as the brush speeds and slows, producing a live contour that sits on the cloth like a shallow bowl of breath. Inside, Matisse composes a spectrum: pale grapes gather into a cool cluster, a dark draught of berries anchors the right, and peaches and apricots carry the warm chord across the rim. Highlights are pulled with quick, opaque touches, not laboriously blended; they read as living glints rather than coded reflections.

Outside the dish, apricots roll toward the indigo fabric, where the painter thickens the paint to give them weight against the dark. These scattered fruits do double duty: they keep the lower corners of the painting active and echo the rounded volumes of torso and stand, strengthening the picture’s network of rhymes.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Up close, the painting speaks through touch as much as color. The ground red is carried in broad, creamy passages whose edges pick up white when the brush drags across dry underlayers. The torso is built from smooth, planar strokes that turn at the edge; black-blue drawing lines are pulled back into wet paint, softening their bite. The dish’s rim is a single continuous stroke reinforced by smaller adjustments. On the indigo cloth, paint thickens and folds, catching light and suggesting sheen without literal description. These varied textures do not imitate materials; they embody them, letting the painting be both image and object.

Light Without Theatrics

As typical in the Nice years, illumination is ambient and humane. There is no spotlight cutting the table into dramatic shards. Instead, light seems to pool across the surface, brightening the torso’s planes, glancing off the dish, and warming the fruit. Shadows are transparent and colored—a cool gray in the torso’s hollows, a deepened red under the dish—so the picture remains breathable. Because light is even, color can carry feeling and pattern can carry space.

Space by Layers, Not Depth Tricks

Matisse constructs depth with overlap and temperature, not vanishing points. The red cloth is the dominant plane. On it sit the dish, torso, and fruits. Behind them, the brass stand pushes forward, almost level with the torso, so the sensation of space is more like stacked fabric than a deep room. The dark green wedge at the upper right barely hints at a wall or screen, enough to close the space without dragging us backward. This compression keeps the viewer near—as if standing at the table—and preserves the modern honesty of the painted surface.

Dialogue with Tradition—and with Matisse Himself

By placing a classical torso among fruit and textiles, Matisse stages a quiet debate between academic tradition and his own decorative modernism. The torso carries the authority of the antique, yet Matisse refuses its usual narrative and instead treats it as one color-shape among others. In this sense the picture converses with his earlier “Red Studio” and with the Nice interiors more broadly: art objects (casts, sculptures, screens) are reabsorbed into an environment where their meaning is formal rather than allegorical. The painting also echoes his long engagement with the oriental rug or patterned cloth as a spatial device, a lesson learned from Islamic art and reinterpreted through the lens of French colorism.

Rhythm, Interval, and the Music of Looking

The painting’s pleasure lies in its measured tempo. Start at the torso and feel how its cool planes slow the eye. Drift to the fruit dish and count the intervals between grape clusters, peach, and berry—near, near, far. Follow the apron of the brass stand and sense its scalloped rhythm answering the cloth’s lower border. Cross to the indigo wedge, where folds speed the gaze before depositing it on the cluster of apricots. Return via the scattered lemons to the torso. With each loop the relationships clarify: round form answers round form; cool counters warm; pattern aerates mass. The room is not a static design but a score for looking.

Meaning Through Design

What does “Still Life with Plaster Torso” finally propose? That art and life can meet on a tabletop when relations are tuned. The plaster cast is a studio tool; the fruit are perishable luxuries; the fabrics and stand are domestic décor. Brought together in balanced color and rhythm, they produce a restorative calm. The painting suggests a way of living with objects: arrange them for harmony rather than status, let each take its rightful weight in the whole, and you will have made a small climate of contentment. It is Matisse’s ethic of clarity made visible.

How to Look, Slowly

Begin by circling the torso with your eyes, noticing where gray turns to lilac and back to white. Drop into the dish and let the grapes’ coolness rinse the warm red. Move to the indigo cloth and feel how the apricots ignite against it. Touch the brass stand with your gaze and sense its metallic green repeating the grapes in a different key. Finally, read the cloth itself—the loops, sprouts, and dotted reserves—as the low hum in which all the other notes sit. Repeat this path; the painting grows richer at the tempo of attention.

Conclusion

“Still Life with Plaster Torso” distills Matisse’s Nice-period ideals into a compact, memorable chord. A cool white statue steadies a red field; fruit, fabrics, and a golden stand add counter-colors and counter-tempos; pattern does the architectural work; light is ambient; drawing is economical; touch remains varied and alive. Nothing is extraneous, and nothing dominates. The painting offers more than a beautiful arrangement of things: it offers a model of equilibrium—how different presences can share a surface, each vivid, none victorious. Nearly a century on, its lesson remains fresh and usable: tune the relations in front of you, and ordinary objects will begin to sing.